Seth Waits and his teammates plunged their paddles into the water of the San Antonio Bay at breakneck speed. Crew members couldn’t ignore the tightness in their shoulders or the muscle spasms in their forearms, but they dug in again and again. Their canoe surged forward and closed the gap between the competing vessel just 150 yards ahead. White-tipped waves crashed into the boat, which threatened to capsize, but Waits and his team continued toward the finish line in a dead heat.

Just 79 hours earlier, Waits had embarked on the Texas Water Safari, which markets itself as the world’s toughest canoe race. Contestants on the 262-mile adventure from the headwaters of the San Marcos River to the town of Seadrift on the Gulf Coast must traverse whitewater rapids, dams and soul-sapping heat — all in 100 hours. To finish, teams must prepare to travel day and night without sleep to cross the finish line by the cutoff.

“I’m the kind of person who enjoys challenges and adventure,” says Waits, who grew up in Lake Highlands and now teaches at Jesuit College Preparatory School. “That’s a big part of what this was.”

Competing in the water safari was years in the making for Waits, who published his race memoir “With the Current, Against the Odds” in 2018. The 36-year-old learned of the race from a Dallas Morning News article the summer before his senior year of high school. Three years later, he was still searching for teammates with the right mix of intelligence, bravery and, perhaps, stupidity. He ultimately turned to college friend Jon Markowitz and Jesuit high school buddy Ben Black with his “crazy idea.”

“Looking back, it didn’t cross my mind that I would say no,” says Black, who grew up near White Rock Lake and now lives in Austin. “Of course I would do that with you, Seth. Why not? It was a naïve response.”

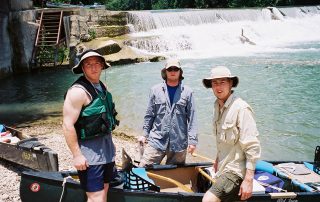

The trio arrived on race day in 2005 with an optimism that quickly dwindled as they scanned the fiberglass canoes and expensive carbon-shaft paddles around them. Other racers seemed to have spared no expense. But as college students, the team had to find equipment that fit its meager budget.

They purchased a used metal canoe from a family friend for a third of the original price. But it was heavy and weighed down further by wooden paddles and gallon-size pickle buckets the group had gotten for free to store food, equipment and medical supplies.

As competitors saw them laying out their gear for check-in, they laughed openly or uttered sarcastic comments. One man, who had raced in the safari many times, stopped at their location, criticized their gear and bluntly said, “I hope you all have fun, but you have zero chance of finishing.”

“That was a turning point for us,” Waits says. “When somebody tells a team of young, naïve, invincible 22-year-olds that they can’t do something, that creates more motivation to prove them wrong. We were really ticked off, but it was one of the best things that happened to us.”

The team was determined to finish after not getting to compete the year before. When they arrived at the starting line in 2004, the crew found a locked gate with a notice that said the race had been canceled because of high water levels.

They bought a six-pack of beer and sat on the footbridge over the San Marcos River, drinking away their devastation. No verbal pact was made, but the teammates knew they would attempt the race again.

When the starting horn finally sounded, the three racers got off to a disastrous start, Waits says. The first time the crew had all been in the boat was 20 minutes before the race, and they hadn’t rehearsed how to paddle or communicate. During the first several miles, they veered into the bank and inadvertently hit another vessel as they emerged from the brush. Shortly after, they grazed a bridge piling, and the canoe emerged facing upstream as a slew of spectators looked on.

But perhaps the most embarrassing moment was when the canoe flipped in front of a crowd at mile 9. The team had bypassed a series of rapids by walking the canoe along the bank, but the water was still turbulent when they re-entered. Large boulders gave way to smaller rocks partly hidden under the water. When they re-emerged — unharmed with gear intact — it was with a renewed sense of unity.

“It stressed how important it was to work together,” Waits says. “It took a lot of courage to keep going.”

The team’s communication improved, but the race didn’t get easier as exhaustion set in. While paddling along the river late at night, crew members passed a spooky field of glowing eyes that belonged to a herd of cattle. Around another river bend, they saw a school bus filled with cardboard cutouts of children sitting on a sandbar.

“We all just looked at it and kept paddling,” Black says. “There are accounts of people hallucinating during the race from fatigue, so we were like, ‘Hey, you saw that, right?’ You know someone put that there just to mess with people. I appreciate the commitment to the cause on that one. That’s a long-range joke.”

But clarity and adrenaline returned as Waits, Black and Markowitz prepared for the final stretch. They knew they were going to finish, but they couldn’t resist one final challenge.

Spying another boat just half a mile ahead of them, they increased their stroke rate until their paddles were churning. They poured their remaining energy into the last mile as sweat dripped down their faces and elbows. But it wasn’t enough. They finished in 58th place, 8 seconds behind the other canoe. Of the 92 registered teams, 73 finished the race.

“It was a different finish than most people see and experience,” Black says. “I was just glad to be done. I have no desire to repeat it, but I’m proud of the accomplishment of pulling it off. It’s a pinnacle experience that I’m glad is in my story.”