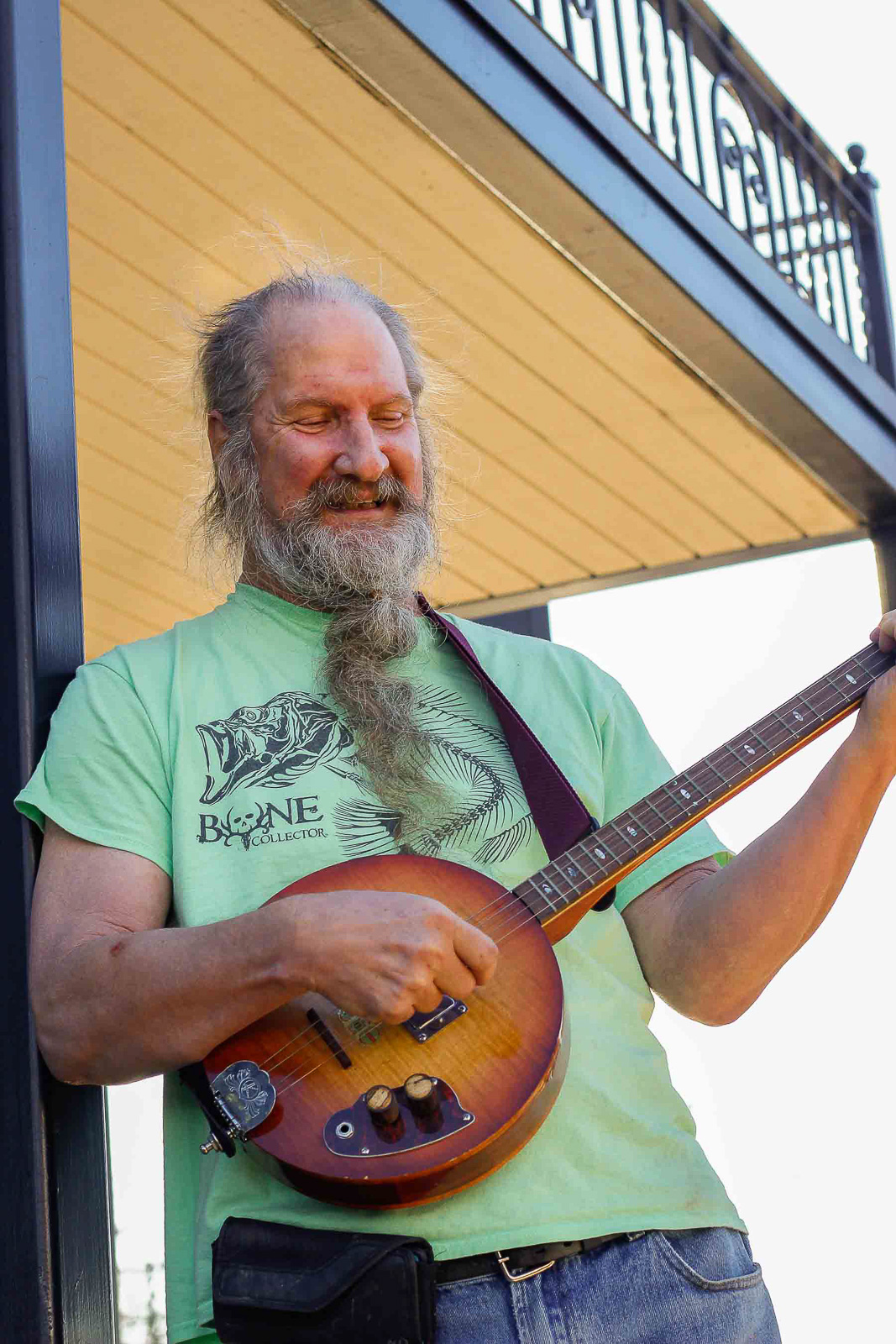

It seems like Jerry Jensen has seen it all, and he can’t wait to share it. He’s a larger-than-life figure, standing tall with a gravelly Texas accent and a long, gray beard.

He spent the ’80s working in the oil industry, traveling Asia and using his status to soak up a wholly unique view of international culture.

“Living in Thailand, I got to see things normal people can’t,” he says. “I went to Northern China before they opened it up to foreigners. Living overseas, the world was my playground.”

Amid his travels, Jensen met a nurse named Heidi in the Philippines.

“I turned on the old Texas charm,” he says. “It was love at first sight.”

Jensen didn’t waste any time. Only a few months later, the couple packed their bags and moved into their new home in Dallas where he’d join the fire department, a job he’d keep for 30 years until his retirement in 2017.

Jensen was happy, working a steady job and living with the love of his life. But settling down wasn’t in his nature.

“One of my supervisors was featured in several woodworking magazines,” he says. “He took me out to his house and taught me on an old-fashioned lathe.”

Inspired, Jensen began to challenge himself with different styles of woodwork. It started out with bowls and picture frames, some of them ending up in featured art exhibitions and auctions.

“I just did it as a hobby to keep myself busy,” he says. “Money is in the background; that’s not my priority.”

He’s taken home awards from the State Fair of Texas and other local festivals for his work, but he continues to add more to his repertoire.

Lately, his projects have become far more ambitious, including projects like transforming scrap parts into a functioning banjo and forging metal to make his own blades.

“I will see something on the internet or talking to my friends and collaborators that sounds like a challenge,” he says. “I want to add this to my next one or do something just a little different.”

Jensen has begun to fuse some of the Asian culture he picked up from his travels into his work.

“I probably incorporate it more subconsciously than consciously,” he says.

He’s currently working on a katana sword made out of scrapped parts and forged metal.

Jensen will only admit that his craftsmanship is a hobby, but his peers label him as an artisan. Even though his work is good enough to merit the distinction, Jensen insists upon giving it all away for free.

“There’s literal blood and sweat poured into that,” he says, holding up a cooking knife made from scrap metal, flaunting the cuts up his arms and the singes on his beard.

For Jensen, his projects help him interact with his surroundings in the most natural way he can. In the same way that he soaked up international culture and met his wife along the journey.

Decades later and thousands of miles away, Jerry Jensen remains the same.