Shirley Ehney photographed at Keller’s on Jan. 12, 2015. Photo by Danny Fulgencio

Two trucks are parked side by side at Keller’s Drive-In on Northwest Highway. They’ve been there a while, as both drivers are taking their sweet time, enjoying a beer or two in the shade of the metal overhang.

Shirley Ehney, a 73-year-old carhop, stands between them making small talk. She lets out a ringing laugh in response to the drivers’ banter before heading back to the kitchen. She has a grandmotherly way about her (probably because she is one) but also a sort of vitality, which she figures is the result of her active lifestyle, working as a full-time carhop for nearly 50 years.

As she passes another car, she nods toward the double-meat cheeseburger she brought out a few minutes ago. “I bet that’s the best burger you’ve ever tasted,” she says.

It’s nothing gourmet, but people say there’s just something about the flavor in the two thin patties stacked between perfectly grilled poppy seed buns, topped with a slice of melted cheese and the usual burger garnish.

It’s the reason foodies from all over the country stop by Keller’s on their way through Texas — and why Ehney has stuck around for so many decades.

“It’s like an addiction,” she says.

Keller’s Drive-in: Photo by Scott Mitchell

Few who regularly travel the thoroughfare have entirely resisted the call of the vintage “Keller’s Hamburgers Beer” sign. The green and yellow paint is chipping, sure, but the slapdash aesthetics only add to its charm. Keller’s appearance reflects the rugged reliability of the food, staff and customers that have sustained it since 1965, when White Rock area resident Jack Keller established the beloved burger joint’s Northwest Highway location.

The menu has not changed — burgers, hot dogs, grilled cheese, fries, tots, onion rings. The prices have barely budged since the beginning. Customers don’t speak into a machine or punch a touchscreen. It’s what Keller calls a “pure” drive-in experience. Drivers pull up and flash their lights. A carhop comes out to take the order, face-to-face, and returns with the goods.

Day after day, year after year, Keller’s delivers a product crafted with care and know-how. “Consistency, that’s the key,” Keller says. “Consistency and quality. There’s no substitute for quality.”

[quote align=”right” color=”#000000″]“Don’t ever do a job you don’t like, no matter the amount of money you make. Always do a job you love.”[/quote]Keller’s meat and produce are delivered fresh every morning, he says, and “when you run out, you run out.” The drive-in magnate reported grossing $1 million in the ’70s, and 40 years later, business is better than ever, he says.

Keller’s opened at a time when drive-in diners were still popular throughout the United States. It operated among famous and well-established roadside joints in Dallas such as Kirby’s Pig Stand and Prince’s Hamburgers. Kirby’s was the nation’s first drive-in when it opened in 1921, and the barbecue joint eventually was dubbed “the nation’s first drive-in empire” before it closed its last location in 2006. Although Prince’s still operates in Houston, its Dallas location on Lemmon closed several years ago.

Keller, too, has closed several restaurants over the decades, including two longstanding drive-ins on Samuell and Harry Hines. But the remnant of his empire is still standing. Perhaps the reason is Keller’s unrelenting commitment to consistency and quality, or the money he has saved on fresh paint jobs or other remodeling projects — or, as Wilma Keller points out, her husband’s head for business and investing.

“He’s smart,” Wilma says with a wink. “I always knew he could do whatever he wanted to.”

Ehney agrees that Keller is “real smart when it comes to his hamburgers.” Even still, she’s amazed at how much business the drive-in continues to garner.

“I guess it’s just hanging in there because there aren’t that many places like it anymore, and [Keller’s] is famous all over the country,” Ehney says.

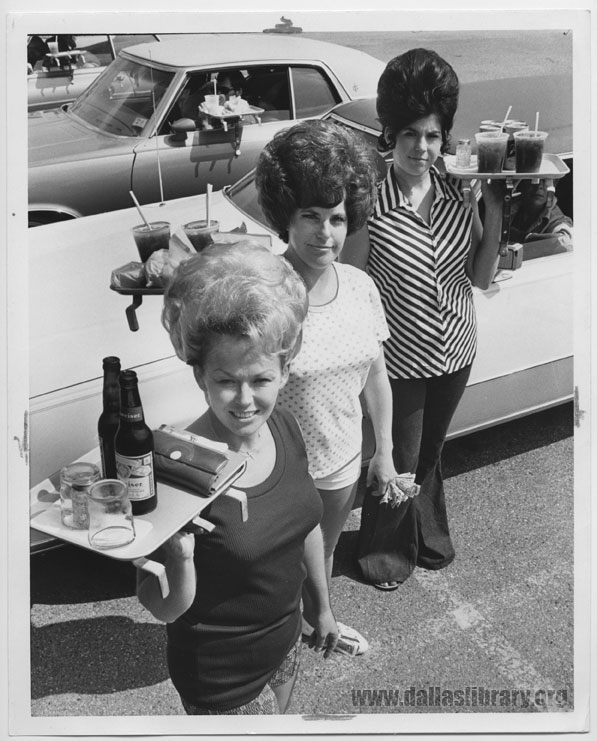

A young Shirley Ehney (middle) poses with two other Keller’s carhops in 1974. From the collections of the Texas/Dallas History and Archives Division, Dallas Public Library

Ehney began working at Keller’s just a few months after it opened. Some people have been parking in her section for years. She knows the bikers, who park on one side of the lot, the hot-rod and vintage-car enthusiasts, who park on the other, and the families who bring their children. No doubt those families’ matriarchs and patriarchs sat in the same spots years ago, beside their own parents.

“We get all kinds of people,” she says. Ironically, many patronize the ’60s holdover because they are seeking a new experience. “I’ve had people come from out of state and get very excited because this is something different.”

Keller says one reason he keeps prices low is because it encourages diners to tip more. The carhops work primarily for tips, and some of them, including Ehney, thread dollar bills through their fingers as a subtle hint to patrons. In the early years, she usually worked nights. Ehney had such a sharp memory, she could handle a large section by herself without writing down a thing.

[quote align=”left” color=”#000000″]See what’s in Keller’s famous no. 5.[/quote]“It came very natural for me,” Ehney says, “and I never took a beer back when I made a mistake, because I always found someone on the lot who would buy it.”

It helped that Ehney was a pretty, capable and friendly girl in her early 20s. Men always flirted with her, she says, although she insists she never dressed provocatively — save maybe a short skirt or two. “I always presented myself well,” she says.

Over the years, she married and had four children, which eventually led to six grandchildren and one great-grandson. Although she passively considered leaving Keller’s to try other things, she ultimately stayed on at the drive-in. After all, she was good at it, and her customers loved her.

Ehney is the only Keller’s carhop who has stood the test of time, although a couple of others can boast a decade or two. The family-like community at Keller’s is hard to beat, Ehney says. She has story after story of when “the girls” (as she and Keller still refer to the carhops) and her customers helped her during hard times.

When Ehney lost her daughter to cancer in 2008 and fractured her foot the same year, her co-workers collected funds to help her get through the time away from work.

“I think that’s what kept me here. I love my job, love the people,” Ehney says. “I’ve made a good living and had a lot of good customers.”

“Don’t ever do a job you don’t like, no matter the amount of money you make,” she says. “Always do a job you love.”