Throughout May, commencement speakers everywhere beseech young graduates to embrace opportunity as they step into a bright future. Each graduate has a story about his or her journey to this day. Some have traversed dark and challenging terrain …

For those, the light is especially brilliant.

A hardened criminal by age 14, Jonathan Garza — supported by people who saw something good in him — barely avoided a long-term prison stint and turned his life around.

A little before midnight on a dark, mostly quiet summer night in 2008, police rolled up on a violent crime in progress near the corner of Forest and Lovers lanes. A dark-haired male of average height and build pointed a gun at two other men. Police promptly arrested the would-be robber, charged him with aggravated armed robbery and locked him up in Dallas County jail.

The detainee, Jonathan Garza, didn’t stand apart from the other inmates. Though physically mature, he was notably younger than the other men in custody at Lew Sterrett Justice Center; Jonathan was 13 and an eighth-grader at Lake Highlands Junior High.

Garza got involved with a gang, he says, because he felt a painful disconnect from his family.

“My dad was a drinker, mom worked all the time, and I had a brother in jail,” he says. “I wanted a family. I got involved with drugs, [both] selling and doing — I smoked [marijuana], did coke, a lot of ecstasy and codeine — and gangs. I was lost, confused and I felt like these people [all of them older] were my family.”

Jonathan describes a progressive downward spiral that preceded the armed-robbery incident.

In eighth grade, for “showing up to school high,” LHJH disciplinarians assigned him a temporary transfer to Christa McAuliffe alternative school, from which he was booted for possessing weed on campus. He left home to live on a series of friends’ couches, in cars and, sometimes, in laundry mats.

“Home was bad. There was always arguing about bills, parents fighting, stress. I didn’t go home. Ever. Out here [the streets] is where I belonged. I was angry, full of complete darkness. I felt nothing. Only a need for basic survival.”

He and his older buddies carried guns — which are easy to acquire in his circles, he says — and they broke into cars and homes around our neighborhood for money.

The armed robbery, he says, came after his drug inventory was confiscated, and he was in “a tight spot” and owed money he couldn’t pay back. He says that day in 2008, which he says included multiple crimes, marked the first time he pointed a gun at someone.

Jonathan spent two weeks in jail before authorities transferred him to a juvenile facility. There, he learned he would be sentenced to a minimum of three years in a Texas prison, and Jonathan says he deserved it.

However, late one night, the judge sent for him.

“She wasn’t even wearing judge clothes when she spoke to me,” he recalls, “but she told me I was going to be released. That I was on probation.”

Jonathan suspects certain members of the LHJH community were working behind the scenes on his behalf, though he doesn’t know for sure, and he chalks the prison deferment to, officially, “a miracle.”

“I guess someone saw something in me that was worth saving,” he says. “But I couldn’t find it yet.”

The gratitude and attitude-change the judge and whomever were hoping for didn’t take hold of Jonathan immediately.

“I got high again. Went to my first probation appointment and flunked my drug test.”

Lake Highlands Junior High football coach Zachary Garza’s first impression of Jonathan was of a “kid who just didn’t care”.

“His first eighth grade year, he was on the football team and in one of my classes,” Zachary says, “but he often didn’t show up, if he did he was late, and he was always in and out of suspension.”

If there was such thing as a lost cause, the coaches concurred, Jonathan embodied it.

“It was shocking to hear about his arrest. Not surprising that he had been arrested, but we were not aware of the extent of his problems,” Zachary says.

But on the first day of his second eighth-grade year, Jonathan visited the coaches.

“He came to our office wearing a shirt and tie and told us he’s changed and that he wanted to play. Of course, we were suspicious,” Zachary says.

After failing the drug test and being threatened with prison for a probation violation, Jonathan says he stopped using drugs and worked up the nerve to implore coaches Garza and Gibson to put him back on the team.

“Through all the mess, I always loved football,” Jonathan says. “And those coaches — they gave me a chance. They became like dads to me.”

Jonathan’s turnaround floored his coaches.

“I have never seen anything like it. He went from a gang-banger flunkie to a straight-A leader, hard-working team member,” Zachary says. “He spent a ridiculous amount of time working out. He later told us that spending tons of time at the gym was his way of staying safe.”

Jonathan went back home, too, and through sober eyes, he saw a family that needed a savior.

His dad was sick, diabetic and hadn’t worked in years. Mom and Dad fought and even separated temporarily. Jonathan took a job working alongside Mom at a factory.

“I was an able-bodied 14-year old now, a big kid — always been big. Always had this [touches beard on chin] — and the work at that factory almost killed me.

“It was 120 degrees in that place, and the work was tough. It hit me that my mom had been doing that job for nine years. That motivated me.”

At Lake Highlands High School, he joined AVID (a program to help kids prepare for college) and the football team. Dad stopped drinking, and father and son forged a relationship.

“He never was exactly the [traditional] father, but we became friends,” Jonathan says.

Things became more peaceful at home. A sort of healing seemed to be taking place. Even Jonathan’s older siblings, who had bailed long ago, started coming around.

“We were finally the family I always wanted,” Jonathan says.

Jonathan was inducted into the National Honor Society. His dad attended the ceremony — a first.

“No, he had never come to anything before,” Jonathan says, “That was big.”

The end of felony probation and related drug tests came and went, without incident.

“Honestly, I had planned on smoking [weed] when I got off probation, but by the time it rolled around, I was too busy. And anyway, I had begun to enjoy getting attention for positive things. I knew that would go away with the first high.”

Things were looking up in all aspects when Jonathan’s father was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. The summer before senior year, Jonathan, his mom (who is 20 years his father’s junior) and older siblings took care of his rapidly deteriorating dad, who died several months later.

The Wildcat football team members and coaches kept Jonathan afloat, he says.

“I cannot say it enough. These people are amazing. I owe my life to them. They supported me. When I say they helped me, I mean they helped me. They gave us money. I just want them to know. Thank them … ” His voice trails off.

The loss of his father was crushing, Jonathan says, but the people around him have, in no small way, empowered him.

And he, them.

His stunning reformation, for example, impacted coach Zachary Garza.

“When you see something like what happened with Jonathan, it gives you faith that anything is possible. It taught us to never give up on a kid.”

Jonathan’s mom has developed lung cancer, a result of cigarette addiction, Jonathan says. She had to quit the factory; it’s not a job one can do with a collapsed lung, the young man notes. The development is bittersweet.

“Now she is a mom to me and my little sister (5). She packs lunches. She is the mom I always wanted. The mom my sister needs,” he says.

Jonathan needs to say something about his past.

“I don’t regret it. The crime that got me arrested. It was the best thing that happened to me… I became a man.”

He says he understands that people will hate him for what he did — the robberies, the break-ins. So he tries to give back, hold his head high and share his story to help others. He’s a living example, he told 700 RISD teachers at a pre-semester assembly, of what can happen when you refuse to believe in lost causes.

Now, he’s planning his high school graduation. With his football prowess, glut of extracurricular credits and straight As, he could have a pick of universities. Instead, he will enlist in the Marine Corps.

He has it all mapped out: “I will serve five years, then, using the GI Bill, I will attend Sam Houston State University, where I will study criminal justice, possibly become a probation officer, buy a house here in Lake Highlands for me and my mom and sister.”

As he told the teachers at that fall assembly, he realizes he has an important purpose. Not many embracers of gangs and drugs return to the world of the living, and he wants to be the breathing example of possibility.

“Those older guys I was running with are doing real time — decade-long and even life prison sentences.”

It is a life, he notes, that generally ends in prison or premature death.

“That is my plan, my goal — to change even one life — to do or say one thing that will turn it around for one person.”

Anxiety and betrayal took Nicole Alozie down a dark road, but today she is sprinting toward the light.

To say Nicole Alozie came from a rough neighborhood would be an understatement. Chaos ruled Lagos State, Nigeria, in the 1990s. Nicole doesn’t remember, but her parents tell the story of being robbed by a gang en route to the hospital the day she was born. In addition to rampant robberies, a religious war that threatened her Christian family was underway. Soon, Nicole’s father arranged for her and her mother to move to the United States. Because of immigration laws, he could not join them.

Mom struggled, working multiple jobs, to give Nicole and her brother, who came along after the relocation, a fulfilling life, and she became a U.S. citizen. Nicole worried about her father, and she endured bullying at school, but developed a thick skin. She blossomed into a girl of unique loveliness — as a high schooler, she’s athletically built and welcomes new acquaintances with a firm handshake. Her long braids are pulled into a thick bundle, and — donning a men’s Hawaiian shirt, a thick gold chain, jeans that snap above the ankle and orange Converse All Stars — her dress stubbornly strays from all known fashion trends. She says the teasing lasted through eighth grade. “Let me show you,” she says, pulling a pair of spectacles from her bag and putting them on; behind the lenses, her deep brown eyes swell. “Yeah,” she says. “Bug eyes.

“Kids made fun of these. They made me antisocial. I can’t see without them, and my eyesight is progressively deteriorating.” Then she removes the glasses, puts them back in the bag, and moves on to the next topic.

By the time she started Lake Highlands High School, she had made both social and academic progress, but things crumbled during sophomore year, she says.

Mom had wanted to start a business, but sensible Nicole had begged her not to do anything to jeopardize the job that paid the bills. Nonetheless, Mom came home one afternoon and announced she had quit the job and used her savings to buy equipment to start a catering company.

A constant fight to make ends meet ensued.

“For a year, we had no money for electricity bills, food, school supplies … anything.”

Around this time, Nicole says, a male acquaintance of the family abused her. Nicole says that her mom cut contact with the accused, but had a hard time accepting the situation and became depressed. Nicole, too, battled depression, anxiety and suicidal thoughts.

Nicole escaped the nerve-wracking environment at home by hitting the track. Track sports are in her blood, Nicole says. She dreams of the Olympics, because of how happy it would make her dad.

She spent hours training every day. But she had a job that sometimes interfered with track and school work. “I make all A’s and B’s,” she says. “I know it could be all A’s, but I get too sidetracked.”

As a teen, she began making her own clothes. “It is a cultural thing in a way — [Nigerian] women sew and make clothes. I made my prom dress,” she says. Not a burden, it brings her joy and a sense of accomplishment, she says. Last year, Nicole and a group of Lake Highlands students voluntarily sewed and shipped hundreds of dresses for Ugandan women.

Nicole and her mom have mended their relationship. “I see how hard it has been for her,” Nicole says. And Nicole has confided in her track coach and guidance counselor, both of whom she professes to “friggin’ love.”

The fondness is mutual, Paula Moore, Nicole’s counselor, says. Nicole often used Moore as a sounding board for both academic and personal issues, but was tough and always hid her troubles from the masses. “She is not afraid to ask for help,” Moore says. “And while she is facing a lot of stressful situations, she’s not going to let the people around her know what’s going on.”

Most of her peers probably don’t realize she faces problems with things they take for granted — she couldn’t afford to take the SAT when she wanted to, or driver’s education, for example; and when she finally took the SAT, she says, she didn’t test well. But, she assures, “It’s OK. If I have to go to community college before I go to a university, I will.” Both will lead to the same destination, she says: medical school and becoming a doctor.

“Maybe a neurosurgeon. I want to do something that will bring a lot of fortune to my family. As a neurologist or neurosurgeon I will move my dad here, travel and see the family I have never met … I will open a hospital and shopping center [in Nigeria].”

Shopping center? Of course, “because the design career will follow the doctor career,” she says.

Paul Holden was troublingly mute during his early years, until his first word saved his life.

Paul’s parents were worried: Their 2-year old hadn’t spoken a word — not “mama” or “dada” or even “baba.” Was something wrong? Their previous two children “were babbling away by 10 months,” mom Anne Cameron says.

But when it counted, Paul spoke.

“Moke. Moke!” 2-and-a-half-year-old Paul said from his crib. Startled by the boy’s first verbalization, the babysitter hurried to the room. Paul was pointing at the ceiling, at a cloud of smoke creeping toward his tiny fingers. The story has been told time and time again, Paul warns, so there exists the possibility of embellishment for dramatic effect: The sitter scooped up Paul and hit the hallway at the exact time the home’s attic fan, all ablaze, came crashing through the ceiling, flames nipping at the sitter’s heels as she rushed the toddler to safety.

“I said my first words the night our house burned down,” Paul says.

The “expressive language delay” had worried Paul’s mom — a clinical psychologist who later became the pastor of Lake Highlands Presbyterian Church — to the point that she and her husband, George Holden, nearly sought out a specialist to evaluate him. She believes it might have been a precursor to difficulties Paul experienced beginning a few years later with pronunciation and reading. With the help of a speech therapist and Montessori-school educators in Arkansas, where the family lived, Paul addressed his problems with words. When the family moved to Texas, when Paul was in seventh grade, the painfully shy young man says he had trouble making friends. He says he went a couple of years, actually, without a friend.

Some people read with effortless pleasure and make friends without trying; Paul, however, had to work diligently at both.

In ninth grade he made the tennis team and joined band and found friends. He plays the saxophone, enjoys band immensely, he says, and recalls the exact moment, playing in concert at a Richardson gym, when he realized he would for the rest of his life love music and performing.

By his senior year at LHHS, the former speech- and reading-hindered, shy kid has become an admirable athlete, a musician, a motivator of classmates — 1,300 students voted in the mock election he and a fellow student of the opposing political party organized during the 2012 presidential election — and he ranks third overall academically in his class.

He says the teachers, coaches and staff at LHHS contributed to his success. The struggles he once faced, he says, “don’t even feel like part of this same life.”

Paul just learned he has been accepted to Yale, where he will follow in the footsteps of his two older siblings, and where he hopes to study science and possibly, thereafter, medicine, he says. He would like to be a doctor, he says, learn a foreign language and help people who need it free of charge.

“I am aware that I am privileged. I want to help people who don’t have those same privileges.”

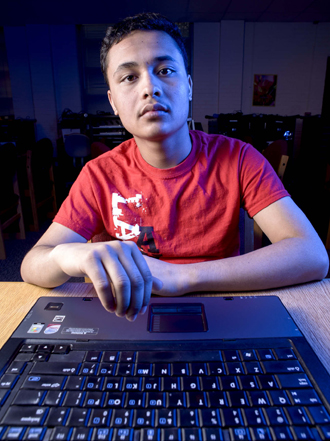

Until eighth grade, Bhupendra Karki had never lived in a home with electricity or running water; now he’s a technology and social-media wiz kid.

Unlike most of the 2013 graduating seniors, Bhupendra Karki didn’t grow up with a cell phone or a video game controller in his palm. In fact, until seventh grade, when he moved from a Bhutanese refugee camp to the northeast Dallas area, he lived with his family — parents, grandparents and younger brother — in a thatched hut with no electricity or plumbing.

They relocated, Bhupendra says, with help from the International Organization of Migration. His new home in the Vickery Meadow area of Dallas had better accommodations, he says, but the social transition was tough.

“It was kind of depressing,” says Bhupendra, a young man of few words but frequent smiles. Through English as a Second Language (ESL) classes and Frisbee club at Sam Tasby Middle School, he was able to foster a few friendships, but for much of the time during the first few years, the soft-spoken, slight-statured Bhupendra says he felt alone in a confusing new world.

It wasn’t an entirely negative time, though. There were things about the new culture that excited Bhupendra. On an almost daily basis, for example, he discovered basic technology that he found “thrilling, surprising,” he says.

By his sophomore year, Bhupendra’s family had moved to an apartment complex in the neighborhood, and he was attending Lake Highlands High School. He joined Wildcat International, a club for ESL students, and began tutoring others. “It made me feel good to help,” he says. He joined the Japanese Club and excelled academically.

Weeks before his high school graduation, Bhupendra is still quiet.

As he introduces himself to the Advocate team, an office staffer passes and reminds him to use his “loud voice” (the directive elicits a grin).

Initial shyness belies the self-confidence and determination driving Bhupendra’s achievement in school. He is an ROTC member and has completed a coveted health-profession internship as well as the driver’s education course. He is an A student — a member of the National Honor Society and Mu Alpha Theta — who has his future mapped out. He will attend the University of Texas at Arlington, he says, where he will study software engineering. His goal: to do something for humanity. To create something, through software and technology — something like Facebook or Google — that will make a significant impact on the way we live.

For him, social networks are more than toys. Those who view Facebook and Twitter as time wasters “don’t fully understand the value of having a connection,” he says.

He credits his parents with instilling not only scholarly motivation and expectations of success but also compassion for those who come from situations similar to his own. His parents organized a Bhutanese Society in Dallas, to which he, too, has contributed time. He even taught English and civics classes to incoming immigrants, helping them to prepare for the U.S. citizenship test.

Teaching in front of a classroom is no small feat for someone who is by nature introverted, he admits, but he is grateful for his opportunities and therefore is pleased to do his part to advance communication among people. Anyway, he says, “They were not difficult to teach, because they are so eager to learn.”

Everything was in its right place for Hannah Willard, until an unexpected tragedy shattered her world.

Hannah Willard is the kind of girl other girls want to hate — pretty, bright, talented, impossibly perfect — but cannot, because she’s just too sweet.

She probably got her friend-to-all-she-meets personality from her dad. That’s how she describes him — “he never met a stranger,” she says of Al Willard, the gregarious jokester who had nicknames for all her friends.

One senses, even after knowing her just 10 minutes, that Hannah is the same way. Her smile is wide; a dash of freckles peppers her nose and cheeks. Her blond hair is, in a certain light, cherry-tinted. She answers tough questions with the poise of a good politician, but sincerely.

Al also was a hard worker, Hannah says, so when, in 2008, he was laid off from his full-time job, he picked up whatever work he could. Sometimes he had as many as three jobs at one time, Hannah says. “He didn’t complain. Ever.” Al did his part to keep Hannah, her little sister Rachel, and their mom Sharon, an art teacher at Northwood Hills Elementary, secure inside their pretty home near Wallace Elementary.

Heartbreak happened a week before Hannah’s senior year at Lake Highlands High School commenced. It was a Saturday, and Al had risen before dawn to deliver newspapers, one of his part-time gigs. Arriving home mid-morning, he crashed on the couch, which was normal. Doctors later would tell the family it was dilated cardiomyopathy — or heart failure — that took Al’s life while he napped in the living room.

Shock. Chaos. A Crowd. No, a community. This stands out about that day, Hannah says.

“First there were ambulances, and the neighbors were there, and we drove to the hospital, but it was too late then — there was nothing they could do,” she recalls. “But that day our home was filled with people. Fifty or 60 people. From that day until his funeral that next Friday, our home was never empty. This community — Lake Highlands — has been completely amazing. I don’t know how we would have made it without them.”

Since senior year began, Hannah has stayed busy — singing in both the Espree pop choir and a capella choir, participating in church and the Girls Service League and volunteering with children. Her good grades earned her entrance into the National Honor Society and the Mu Alpha Theta math honor society. She played the lead role of Nellie in the spring high school musical “South Pacific,” a charge that required 15 to 30 or more hours of rehearsal a week for months. She admits that staying busy is one way of coping with the potentially paralyzing pain of loss. Despite the fact that the day we spoke with her was Al’s birthday, Hannah shows no signs of weakening.

More than one LHHS staffer, including counselor Pam Mitchell, uses the adage “she lights up a room” to describe Hannah. You can’t blame them. She does.

She feels uplifted by the people around her — her sister and mom and her friends and teachers at school — she says, and she anticipates a fulfilling future.

“I am going to Texas A&M,” she says, “and I am going to study elementary education.” No surprise — she loves kids and has years of nanny work and babysitting under her belt. Until summer, she is interning at White Rock Elementary, where she teaches fourth-graders.

“I love children, and my mom is a teacher,” she explains, adding that she hopes to return to RISD as an educator.

When asked, given her stage experience, if she wouldn’t prefer to give Broadway a shot, she says, in the mature manner of a person much older, that while she wishes to continue singing in college — adores singing and performing — she wants to be realistic. And the idea of teaching young children is expressed by Hannah with the same enthusiasm a less grounded person might use in announcing intentions to be a movie or pop star.

“There’s nothing better than working with kids and seeing that look in their eye, that light bulb sparking when they get something you are teaching. That is it. That’s where I want to be.”