What it means to be part of The Greatest Generation

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=umwFsYX5wDQ] We wait alongside them in the grocery checkout line and hurry past them on the street. They are members of our churches and grandparents to our children, but how often do we pause to ponder the content of their lives?As teenagers and 20-somethings, they traveled to distant countries, knowing they might die there, and returned to lives forever altered by their experiences. They risked their lives, left jobs, and cast passions and aspirations aside until their missions were fulfilled.

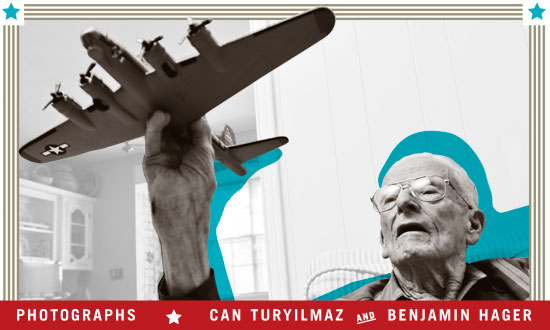

Indeed, all who served in World War II — in battle or supporting roles — deserve unyielding gratitude, but as each Veterans Day passes, the time for thanks dwindles. We can still shake their hands and hear their stories, but for how much longer?

According to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, the ranks of World War II vets are shrinking by about 1,200 a day nationwide.

A few of those who have retired in the Lake Highlands area take time to recall, for those of us who weren’t there, an era that shaped the world.

If you run into one of them today, it might be the right time to say “thank you”.

“It got so close that I was face to face with the German pilot.” — Morris Todd

Germans had just shot down his fighter jet, and he was parachuting into hostile territory. His vision was obscured by blood, but he made out an Me-109 aircraft heading his way.

“It got so close that I was face to face with the German pilot. I could see his eyeballs, and I know he could see mine. Maybe he saw all the blood and didn’t want to waste ammo — I don’t know what it was — but he didn’t shoot me. He waved at me, I waved back, and he was gone.”

This narrow escape was just the beginning of WWII tribulations for Morris Todd, a lead navigator for the Air Force on a mission to bomb an enemy synthetic oil refinery. After bailing at 24,000 feet, Todd, with a “flattened” nose and bloody face, landed in a wheat field where he was greeted by an intimidating cast. “What I first saw was a civilian with a rifle, a soldier with a pistol and a little fat girl holding a sickle,” he recalls. “Even if I’d tried to run, I don’t know where I would have gone. One of them, I don’t remember which one, said to me, ‘For you, the war is over’.”

Todd and the surviving members of his crew — two didn’t make it — were taken prisoner and thrown into a pig pen for the night. “The ground was covered with droppings; we couldn’t lie down. Just stood there through the night.” While waiting, Todd shifted his broken nose, acquired sometime during the attack, back into place. The next day Germans put the American POWs on a train to Stalag Luft in Barth, Germany, which would be their home until the war ended about 11 months later.

Todd remembers details from the ride: “They put us in this compartment of the train … the guards on the train wore Nazi armbands. Out the window, you could see this beautiful forest. A reindeer with a full rack of horns ran alongside the train for a few minutes; then he ran back into the woods.”

In prison, some American soldiers traded their allotted cigarettes with guards in return for radio parts. After several months they were able to tune in to BBC, and learned when the war’s end was imminent.

“The Germans and their news stations kept reporting that they were winning, but we knew the truth,” Todd says.

When it ended, “it was an amazing deal,” he beams. “We flew to France to camp Lucky Strike. They threw our clothes in a pit and disinfected us in the shower.” After about two weeks at the camp, he and a buddy withdrew their accumulated military pay, about 5,000 francs, and toured France, stayed in hotels, and ate at cafés. “Clean sheets, good coffee, bacon and eggs: We were living in luxury.”

Following his service, Todd attended college at Oklahoma University and worked as a petroleum engineer until retirement.

It was just after the war, on a visit with a friend to the Naval Air Station in Norman, Okla., that Todd met Molly, the Navy WAVE who, later that same year, would become his wife.

“I’m here to take the place of a man.” — Molly Todd

Molly Todd was a communications officer at the Naval Air Station in Norman, Okla., and a member of the Navy WAVES, a division of the Navy comprising only women. WWII did not change the lives of only those who fought, but also of an entire generation, Molly Todd says. This was especially true for women who began working on farms and taking jobs in factories, on assembly lines and in non-combat military positions. Women were expected to stand in for men who went to the front, she says. “We were told, in the Navy, that the women would replace the men for sea duty, so when I reported, I told the officer, ‘I’m here to take the place of a man.’ That made him laugh.”

Molly Todd is still quick-witted. She answers the door of her Lake Highlands home — where she and Morris have lived for 10 years — wearing the Navy WAVES cap that was part of her uniform in the 1940s. The service in the Navy gave her a chance to do what she felt was her part to support the war effort.

“Everyone was involved. Everyone felt the need to do something,” she says. “I feel like I did my duty.”

She spent many years following the war teaching kindergarten, and this month, the Todds will celebrate 65 years of marriage.

“‘My God, there are about seven of them back there.” — Stacy Naftel

It was July 4, 1951, and young pilot Stacy Naftel, flying a B-45 Tornado, was on his second-ever mission. Under the cover of night, he and his crew were to gather data about a supposed military complex in northeastern Manchuria. The men were 250 miles from their destination and 35,000 feet in the air when something hit the window.

“It looked like a Roman candle bounced off the glass and then another off the wing,” Naftel says. “I looked below us. There was nothing but darkness. So I asked my co-pilot to turn and see if anything was behind us.” A few seconds later the co-pilot responded grimly, ‘My God, Stace. There are about seven of them back there.’ ”

The next 30 minutes were spent avoiding the fire of seven MiG fighter jets. “They were lined up in an echelon formation, where one would shoot until it ran out of ammo, then another would take its place,” Naftel explains. “We went into a series of corkscrew maneuvers, varied speeds and altitudes, and we generally tried to shake them and spoil their aiming stability.”

It worked.

“The only fireworks we saw that Fourth of July were enemy fire,” Naftel quips.

As traumatic as the experience sounds, it’s what he wanted. For his 25-year-old self, he says, “this was an adventure.” He aspired to be a photographer, but soon realized that the service paid better. Plus, his buddies were signing up in droves, and he didn’t want to miss out.

“All of my classmates were enlisting — they told me not to accept anything other than the Air Corps.” Freshly graduated from his New York State high school, he took his buddies’ advice. Within a year, Naftel was in a pilot-training program. He flew jets throughout WWII, the Korean War and Vietnam War, and mentored new pilots. In all, he served 33 years, and retired as a colonel.

Today, in the closet of his Lake Highlands home — where he has lived with his wife, Bette, since 1974 — he hangs his pilot uniform, which still fits him; and he displays a Silver Star, the military’s third highest decoration for valor in the face of the enemy. The citation that accompanied the medal notes that Naftel fulfilled his call to duty and never backed down, even when backing down would have been acceptable because of the extreme danger. It reads: “The technical proficiency, exceptional courage and devotion to duty displayed by Captain Naftel were in keeping with the highest tradition of the service, and reflected great credit on himself and the United States Air Force.”

“I worked hard, learned a lot, and saw the world.” — Howard Riggs

In 1943, when the military was drafting his high school classmates, Howard Riggs joined the U.S. Navy — thankfully, he says, he was allowed to finish his senior year before reporting for active duty. Today, after living 40 years in the White Rock Hills area of Lake Highlands, he lives with his wife, Glenn Eva Riggs, at C.C. Young retirement community in the White Rock Lake area.

Straight and tall, wearing a neatly pressed polo-style shirt, Riggs walks into the cafeteria and offers a firm handshake. He clutches an antique brown leather-bound photo album. Inside the book are images of smiling 20-somethings in uniform, Chinese children in a shipyard, beautiful beaches, vast Naval ships and striking examples of Asian architecture, including Bejing’s Forbidden City.

In China, Riggs supervised a coal storage plant, and although the warehouse in his area once burned to the ground in an impressive fire, Riggs says destruction and fear were not much a part of his World War II experience. Though it interrupted his education and career, Riggs says he was grateful for the opportunity to travel and to learn leadership skills and decorum.

“I did what I had to do,” he says, “worked hard, learned a lot, saw the world, and had fun.”

He was recalled for the Korean War in 1952. By then, he had graduated from college at Washington University, just married Glenn Eva, and was climbing his way up the corporate ladder at Safeway, where he eventually worked 40 years in advertising.

He says, bluntly, about his Korean call to duty: “I didn’t like that; but I just had to do it.” Riggs spent 24 months loading ships in the Philippines before finally returning home.

“When I returned to work, I found I’d been replaced by a guy I’d hired,” he says with benign irritation.

He remained in the reserves, and retired from the Navy as a commander in 1962 — in the ensuing years, he and his wife had two children, five grandchildren and four great grandchildren.

In October, Riggs traveled to Washington, D.C., courtesy of the Honor Flight program, which allows WWII vets to see the WWII memorial.

Read about the Honor Flight of Dallas, an organization that aims to give veterans an all-expense paid, overnight tour to Washington, D.C., to see the National WWII Memorial.