Each of us remembers important days differently. Some recall in great detail where they were at the time the Berlin Wall fell or a president lost his life, while others rely on grainy video, old snapshots or history books for understanding. But eyewitnesses to history are all around us. Their first-hand stories add another dimension to the tales and images so ingrained in our minds.

Here are some of their stories.

As told by Scott Spreier, who was in Washington, D.C., for the dedication of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial

“I was in college during the Vietnam War, goofing off and making bad grades. In the town where I went to school, if you dipped below a C average, you were eligible for the draft. Because I was young and stupid, instead of waiting for the inevitable, I joined the Air Force and volunteered for, but was never sent to, Vietnam. Instead, I spent the war years working in Intelligence from Washington, D.C.

I grew up in a small town where patriotism ran high, but after two years of the war, I began to sense there was something terribly wrong with it, especially as friends and colleagues of mine began to return from Vietnam and discuss it. Though I was against the war, I had always felt a little bad that I wasn’t sent, and grateful to those who went and fought. In 1982 I learned the Vietnam Veterans Memorial was to be dedicated. I lived in Florida, but it seemed necessary that I go. I flew into D.C. the day of the dedication, and what struck me, and what I will always remember, was how bittersweet it was. It was very much a ceremony by the veterans for the veterans. Politicians and probably much of the public seemed to want to forget rather than remember. The highest-ranking politician to speak at the dedication was a senator, I believe it was Sen. John Warner, but it didn’t seem fair or right that others were not there.

There was a parade, though, and what got to me was the sight of veterans — many in uniform, in wheelchairs and obviously bearing the scars of the war — cheering other veterans. It will always stick in my memory as an important day. I know I would have felt regret if I had not attended. To this day, the Veterans Memorial in D.C. is a powerful and healing monument. I think its presence has contributed to the respect and honor with which we view veterans now, and time has allowed for the bitterness and anger to subside.”

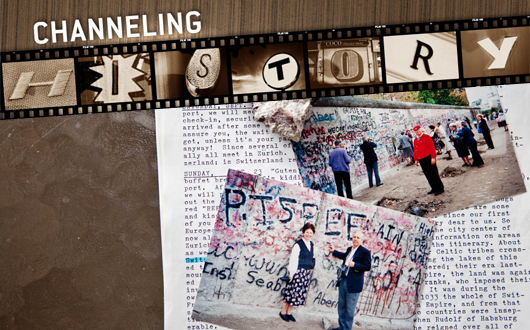

As told by Elinor Pace, who was in Berlin when the Wall came down

“My late husband, Madison, and I arrived in Berlin the day after so-called “Checkpoint Charlie”, the point at the Berlin Wall between West and East Berlin, was torn down. We were with a tour group at a hotel in Dresden. At some point we heard what sounded like gunfire, and we feared that violence had broken out. But soon, it dawned on us that it wasn’t fighting but rather people celebrating in the streets. The people were overjoyed with their newfound freedom.

We had the opportunity to witness the incredible difference between the two sides of the country. Crossing from the east side to the west side of Berlin was like crossing into another world. The western side looked like something out of the early 1900s. Everything was badly in need of paint and repair; it was dark and soot covered. But the people were so excited to be reunited that they flew flags from every window — it was the most wonderful thing. Every house flew the German flag, which was something they were never allowed to do under the communist rule. Having lived through WWII, we all understood the magnitude of what was happening. We managed to chip a bit off the wall and we were surprised at how difficult that was, even with a hammer. ”

As told by Don Lee, who grew up near historical train tracks

“Friday, April 13, 1945, just before noon, I stood across from the Southern Railway tracks in Buford, Ga., and watched the train go by that was carrying the body of President Franklin Roosevelt. I will always remember that event. The train was moving very slowly, and people lined the railroad tracks for as far as you could see both ways. As I recall, his casket was positioned on the back of the train with soldiers surrounding it. He had died the day before in Warm Springs, Ga. — he was sitting for a portrait when he fell over dead from a stroke. His funeral was held the next day, Saturday, April 14, 1945 in Washington, D.C., and he was buried in New York.

These were the same train tracks that ran many, many troop trains during World War II. We lived very close to the tracks. When a troop train came through, we kids would run down and wave at the soldiers. No air conditioning then, so the windows would be open, and the soldiers would wave and throw out candy and chewing gum to us. This was a real treat because these items were rationed then. I have often wondered how many of those soldiers never returned from the war.”

As told by Scott Causey, who was at Parkland Hospital the day John F. Kennedy died

“I was in the ninth-grade when my mom took my brother, sister and I to the corner of Lemmon and Mockingbird to watch John F. Kennedy’s motorcade pass. After waving at the president — I was so close I could have reached out and touched him, it seemed — we returned home to make lunch, and soon after heard a report that Kennedy had been shot and that his motorcade was headed to Parkland hospital. My mother took my brother and sister to school, and somehow I talked her into not taking me to school at Cary Junior High but to work with her. A social worker at Children’s Medical Center at the time, my mom had an office almost directly under Parkland’s emergency room.

We were one of the last cars allowed inside the back, gated entrance before the area was cordoned off. I spent the next two hours or so sitting in the emergency room with the likes of Sen. Ralph Yarbrough and CBS’s Dan Rather. With no internet and no cell phones, reporters fought each other to use the two pay phones in the room. The bloody convertible limo sat just outside the window. Eventually, a hearse parked next to it. No one ever asked who I was or asked me to leave.

I am 60 years old now, but I will never forget that day. Several months later, the event was being discussed on a local radio station. I called in and told them about my experience. They didn’t believe me. Even some other callers said they doubted I could have been there. I suppose a 14-year old kid just doesn’t have that much credibility. My mother is now 83, and she can still tell you about it.”