Photography by jessica turner

On a Tuesday afternoon, a beaming strawberry-blonde teacher stands outside the Lake Highlands High School classroom where she has taught history for 24 years.

Passing teens pause to chat. She tells one she is sorry, but he’s not eligible for tomorrow’s field trip to a museum Downtown. He hangs his head in mock despair, yet smiles as if he knew what she would say.

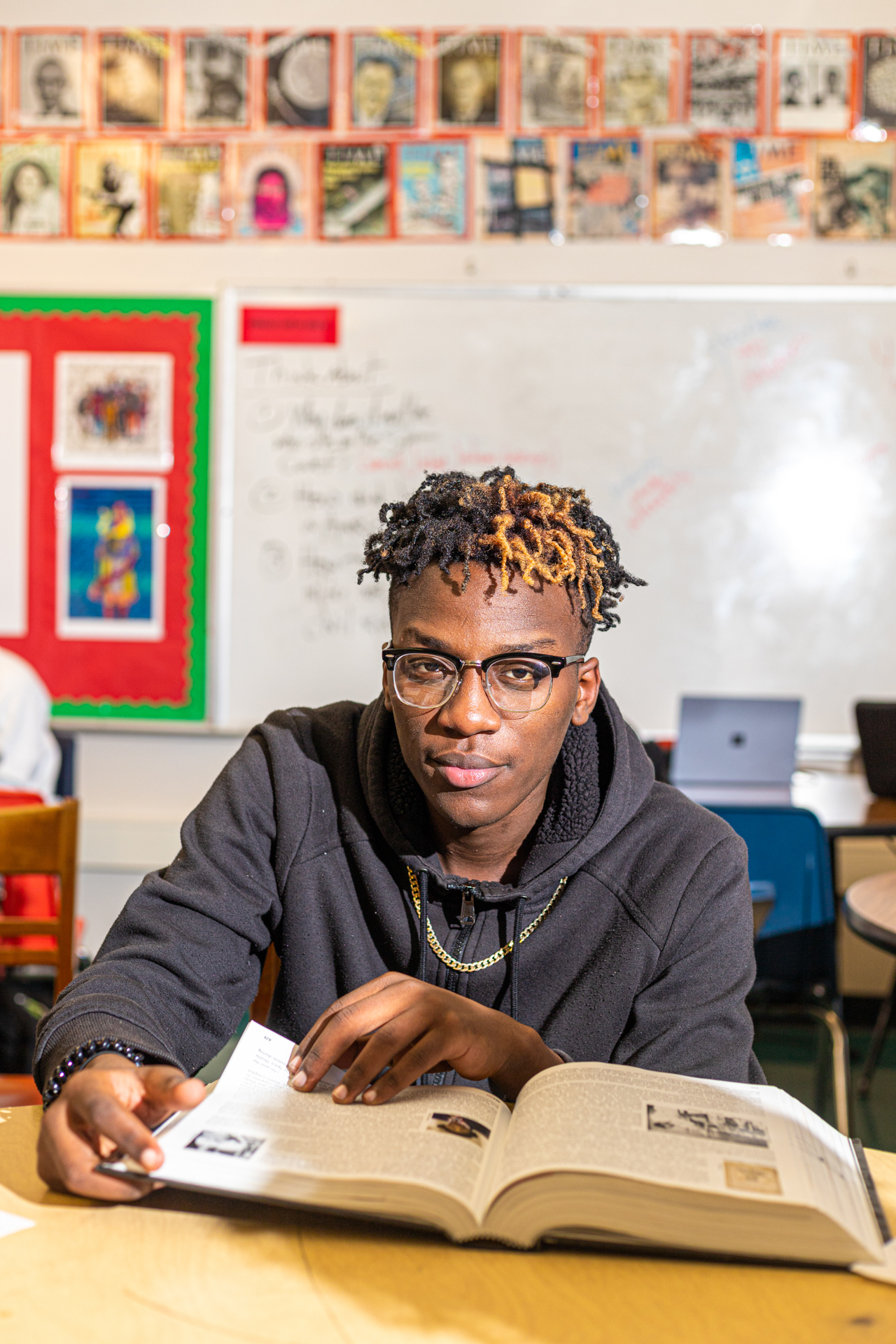

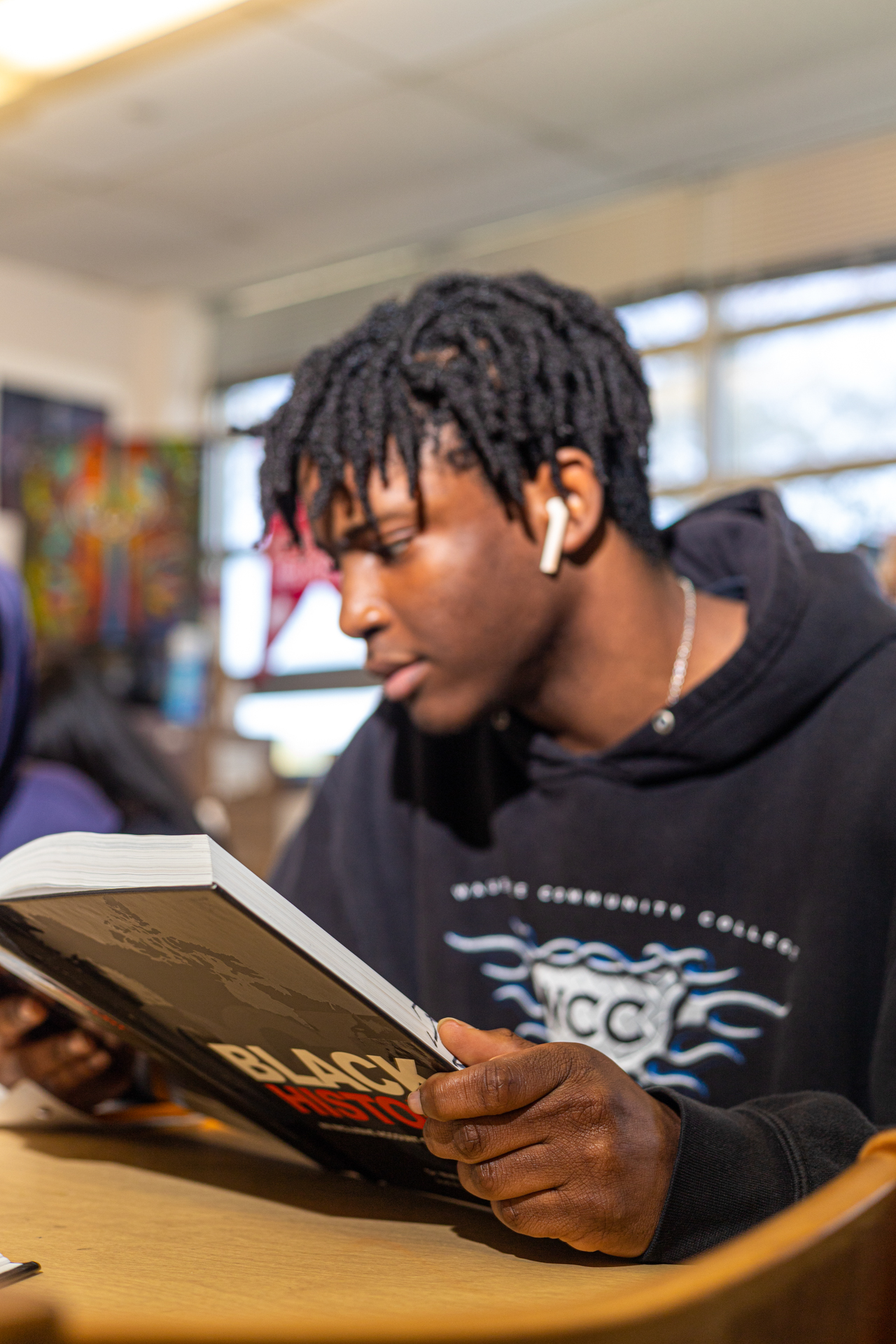

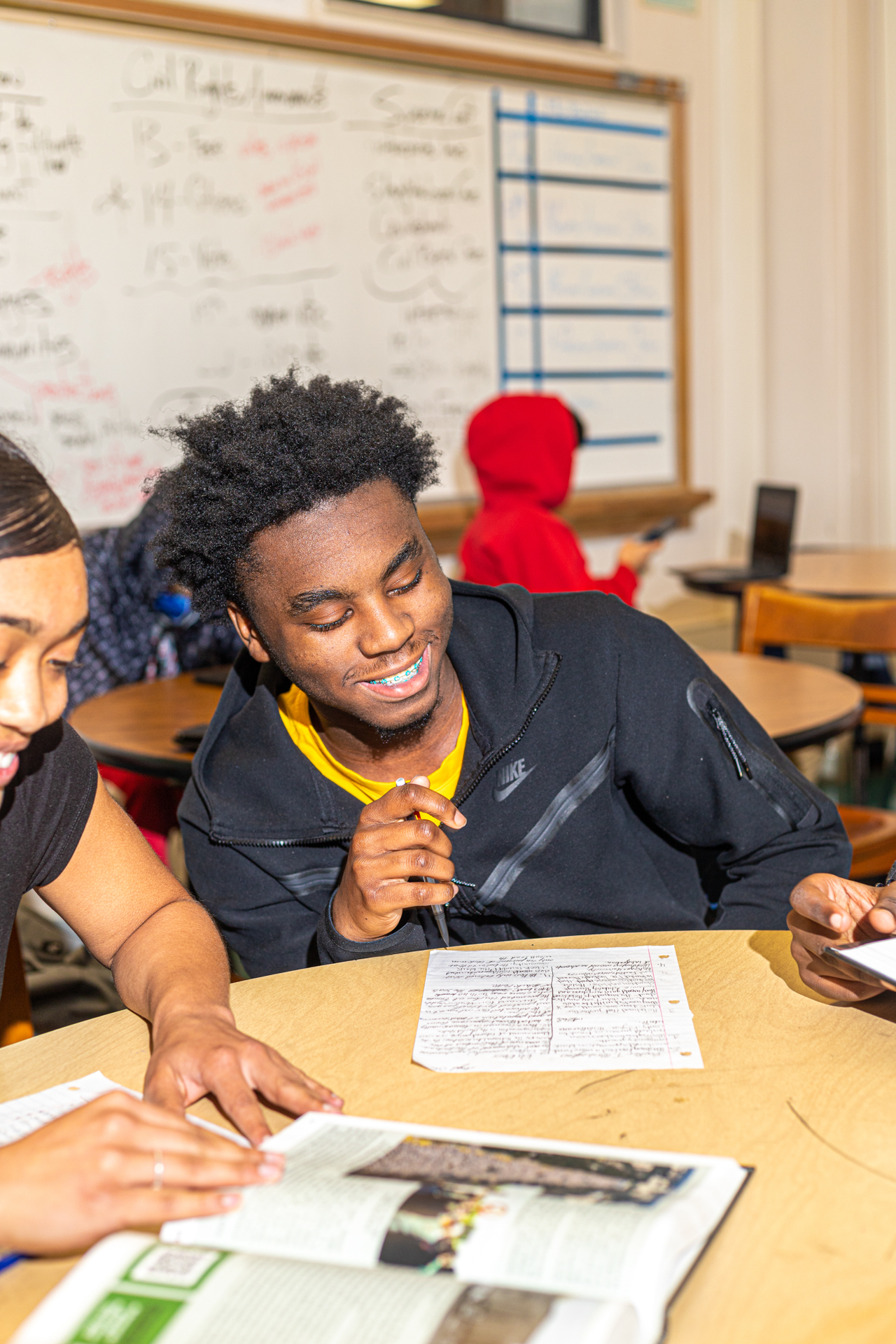

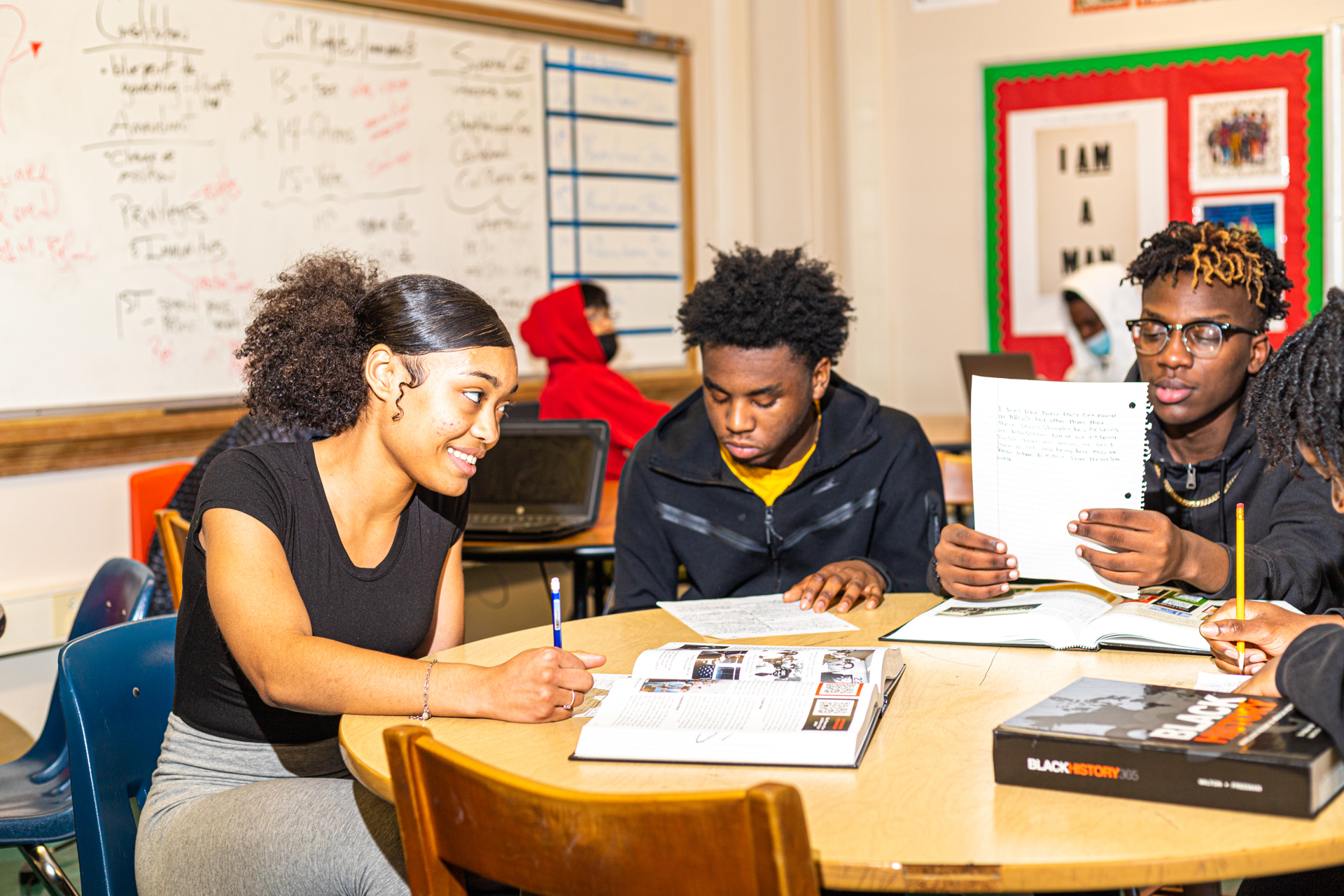

The curriculum Casey Boland teaches on Tuesday and Thursday afternoons — focused on the history and culture of Black Americans — differs from her other courses.

Class starts — today’s lesson is about events leading up to the systematic, state-sponsored persecution and murder of six million Jews by the Nazi German regime.

“Why in the world, as an African American studies class, are we visiting the Holocaust Museum this week?” Boland rhetorically asks the class. “Remember, it’s the Holocaust and Human Rights Museum. The steps that go into producing autocracies and genocides are the steps that also led to situations in America where people of color are treated as second-class citizens.

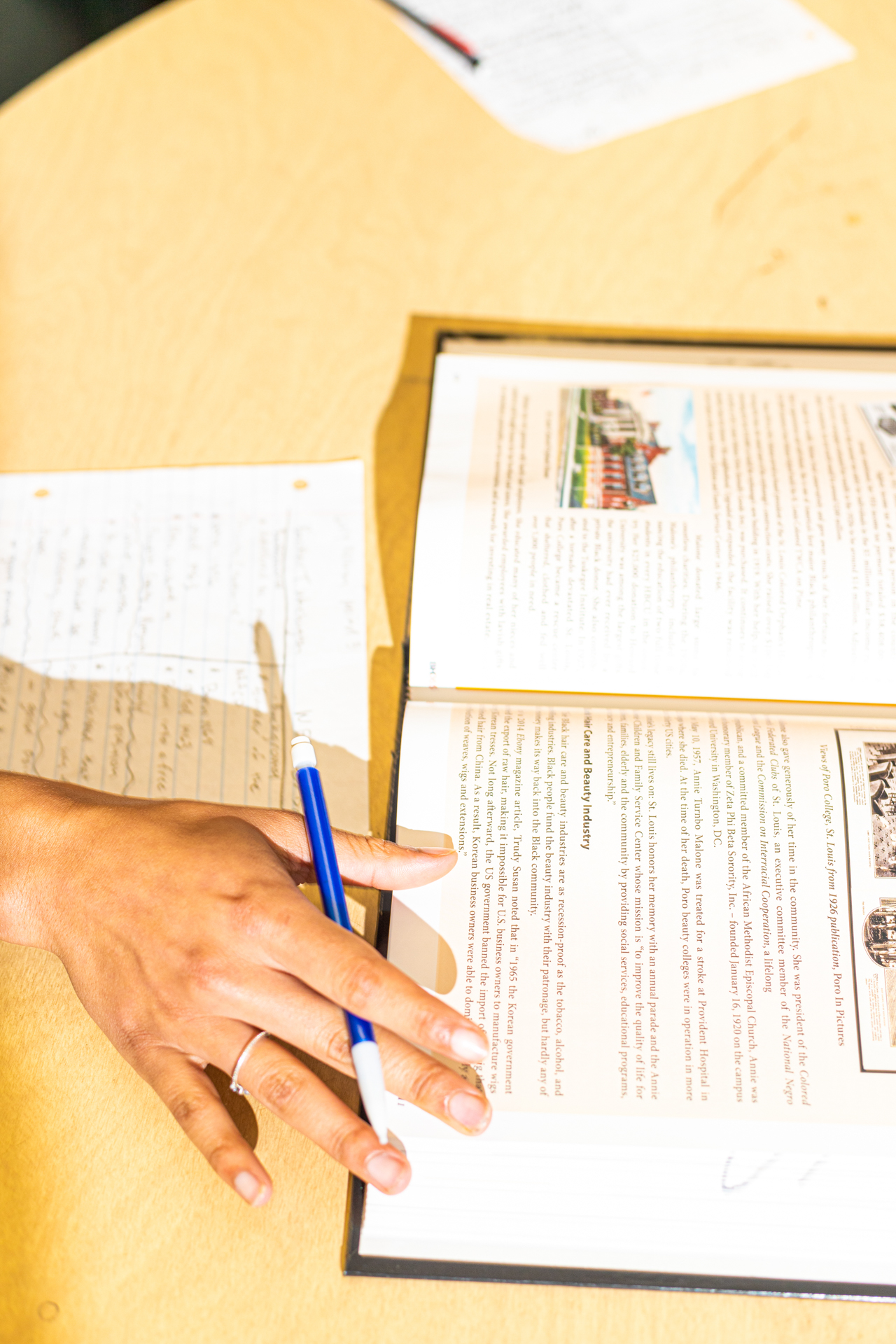

“I want y’all to take some notes. This is going to get deep and heavy today.”

In April 2020 the Texas State Board of Education approved the elective African-American history course for grades 9-12. Berkner piloted it in Richardson ISD last year. This is the first time LHHS has offered it. Boland — who has taught college-level history for decades and believes “Black history is history” — was excited to lead the class, she says. But there was some pushback, because she is not African-American.

Student Fathia Fasasi says when she saw a white teacher at the helm, she almost dropped.

“Honestly, I was discouraged. I thought she was going to be like other teachers I have had, sugarcoating things. Now, I am so glad. She knows what she’s talking about.”

About 100 students, three of them white, are enrolled in Black studies this semester. Fasasi points out that in her other classes, mostly advanced placement, the demographics are the opposite.

“Look around this room,” she says. “The only white person is …”

“Me!” Boland says, smiling, but adding that the last thing she would ever allow is for this class to become a joke. The reason she is teaching it, she says, is that she is the only qualified teacher available right now to lead the class.

“In an ideal world, a Black teacher would teach Black studies class,” she says. “But it came down to, I teach the class or we don’t have the class.”

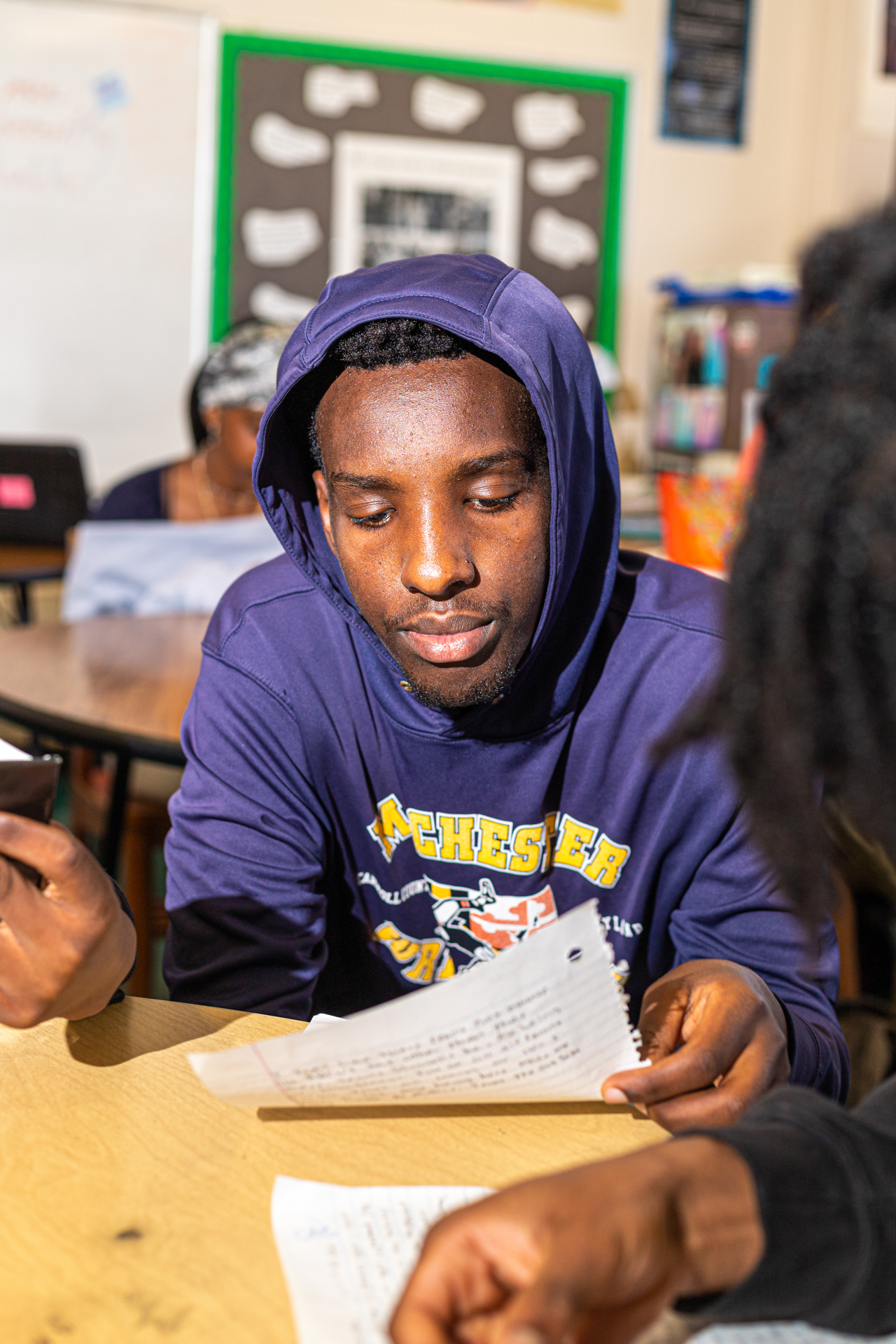

Boland says she has learned as much from listening to her students as they learn from her.

“I love doing this because of the importance of race relations and all the stuff going on in the world right now — all of the reasons that I should — but really, intellectually, academically, I am learning an astounding amount of things for someone at this point in her career.”

Fasasi and the pupils flanking her, La’Miya Sparks and Keyilah Rowe, have mixed feelings regarding the enrollment of more white classmates. On one hand, they like having what Sparks calls a “safe space” for discussions about hard topics. On the other, they think their white peers, like anyone, could benefit from the material.

Fasasi says she is studying the civil rights era in her regular U.S. history class, and this class is different, deeper.

Rowe adds that in other history classes she has been led to believe that America was always right, justified and “the good guys.”

“At a point, I started to realize that if I was in another country, I know we’d learn different stuff about the United States.”

Sparks adds that, before taking Boland’s class, she would often laugh along when her friends made racially charged jokes or comments. Now, armed with more knowledge, she tolerates it less, she says.

When discussions turn to racial inequity, police brutality or systemic injustice, Black studies students say they feel better equipped to engage in intelligent conversation.

“This class gives you so much evidence to help you make your case,” Howe says.

Olivia Fawkes, one of the white students enrolled in the course says that yes, it can be uncomfortable to be in a class where she learns of atrocities committed against Black people by white Americans, but taking part in educating her generation is worth some discomfort.

“Those are my ancestors, and I do not think the people in my class think that that’s who I am, but it is so important for me to know about it, to be here, to do what I can, when I can, to dismantle those (unjust) systems and beliefs in my community.”

Follow the official Instagram of Lake Highlands High School Black history classes at @lhhsblackhistory