A man sits on the bench at the bus stop with his head in his hands as he begins to weep. In the span of two and a half hours, he’s been denied housing, a job and a loan. Down to his last pennies, he doesn’t know what to do.

A man sits on the bench at the bus stop with his head in his hands as he begins to weep. In the span of two and a half hours, he’s been denied housing, a job and a loan. Down to his last pennies, he doesn’t know what to do.

Then the simulation ends, and the man is back to being a Richardson ISD teacher participating in the Cost of Poverty Experience at Mockingbird Community Church.

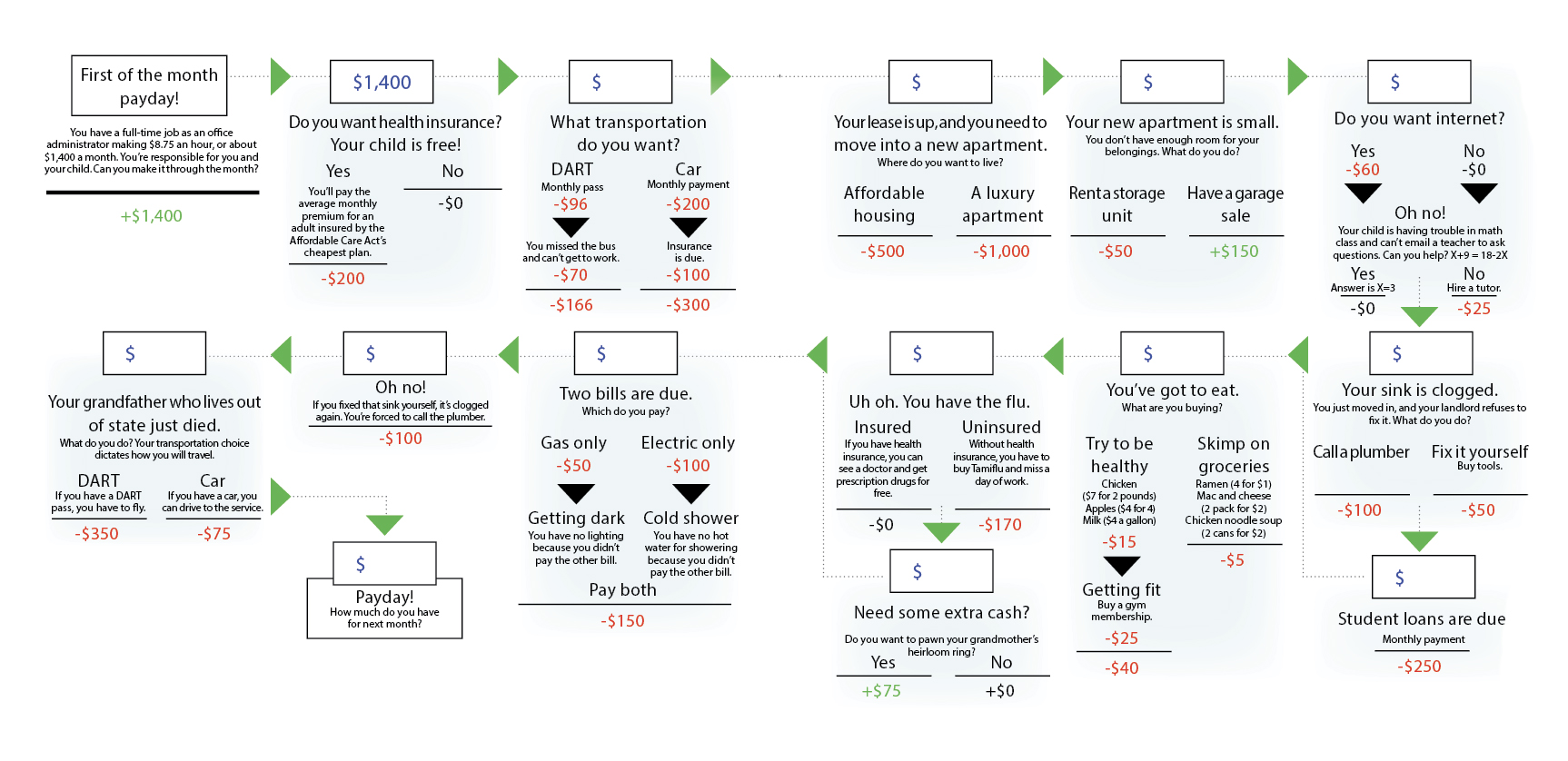

The role-playing exercise assigns participants a new identity, occupation and level of education. They are then asked to live a month in those shoes while navigating obstacles that are common in a low-income environment.

The scenarios that ensue are fake, but the tears shed are often real.

“You have to help [participants] understand what real people are facing,” says Rebecca Walls, who facilitates the Cost of Poverty Experience, also called COPE.

The simulation starts in a large room at Mockingbird Community Church on Ellsworth Avenue. The rooms surrounding the entry have been converted into a school, grocery store, pawnshop, health clinic, bank and more. There, participants face predatory lenders, negligent landlords and discriminatory judges.

“The first few times we did it, every time was so serious,” Walls says. “I could hardly talk when it was over. If I’m a landlord, and people want to pay partial rent, I have to say, ‘I’m a busy person. I’m not going to be here for you to come by twice in a month.’ Then they get evicted, and I have to change the locks and move their junk to the curb.

“It took me a while to follow the rules — to actually do what is supposed to happen instead of giving people a break all the time.”

COPE started in 2016 as a program of Unite Greater Dallas, a nonprofit that connects church leaders with community groups to meet the needs of the city. The first participants were churchgoers, followed by teachers and administrators.

Walls has led the simulation for educators at more than 10 RISD schools, in addition to some in Fort Worth, Carrolton and Farmers Branch. A group of Dallas ISD principals has also completed the experience.

“What I’ve come to understand is that young teachers are reluctant to go into really hard situations because they haven’t been equipped and encouraged to go that route,” Walls says. “If they do go there, they have to develop a layer of protection around their hearts to cope with what they’re seeing. We’re chipping away at that protection.”

The goal isn’t for teachers to lower academic expectations for low-income students, but to rekindle empathy that will affect how they make decisions. For example, impoverished students without money for vacation may feel left out by a writing prompt, such as “Where did you travel this summer?” Armed with that knowledge, teachers could choose a more inclusive topic.

After staff experience the simulation, Walls hopes community partners will come alongside them to provide supplemental volunteers and resources when the schools fall short.

“When a district says, ‘We wish we could do more, but we don’t have the resources,’ that’s exactly what the community needs to hear,” Walls says. “Our job is for the community to come around the families and help them figure out how to make life work.”