Darwin Payne was a 26-year-old reporter for the Dallas Times Herald the day President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas. Assigned to the rewrite desk, Payne dashed to Dealey Plaza and wound up being one of the first to speak to Abraham Zapruder about the home video that vividly froze the assassination in time.

Now professor emeritus of communications at SMU, Payne is author of several books, including the university’s recently published history, “One Hundred Years on the Hilltop: The Centennial History of Southern Methodist University” and “Big D: Triumphs and Troubles of an American Supercity in the 20th Century.” He was one of the researchers who helped create the Old Red Museum of Dallas, and he occasionally speaks about the assassination at the Sixth Floor Museum and the Dallas Historical Society.

His recollections of Nov. 22, 1963 actually begin in October.

The Stevenson incident

“We expected something might happen, because we’d had all these right-wing extremists for more than a decade making trouble in the city. One month before Kennedy came to Dallas, [then-U.N. Ambassador] Adlai Stevenson came, and I went to hear him. A lot of the right-wingers were there, members of the National Indignation Convention. I’d seen in the paper the night before that leaflets had been distributed announcing Kennedy’s visit, and I told my wife, ‘Something’s going to happen. We’ve got to go down there tonight.’

“There was a huge crowd of people who took command, and they wouldn’t let Stevenson speak when he was introduced by [Neiman Marcus legend] Stanley Marcus. The leader of the group had a bullhorn and shouted, ‘Mr. Ambassador, we demand answers to these questions.’ About half the people supported the protestors and half supported Stevenson. The police had to come drag the organizers away. They had upside down flags and would cough incessantly while he spoke.

“After the speech, he went out a side door to Stanley Marcus’ car, and there was a gang of protestors waiting outside with signs, who started rocking the car, trying to turn it over. Stevenson got out of the car and was hit with a sign. He asked, ‘What kind of animals are these?’”

The attack made national news, and Stevenson reportedly warned Kennedy the atmosphere in Dallas was too dangerous for his upcoming trip.

“City officials were terribly worried,” Payne recalls, “and passed a new ordinance regulating how many people could gather. The city tried to make everything safe in the month before he came, and the right wingers didn’t really show up. I admired Kennedy and had voted for him,” says Payne. “He was the first president I had voted for.”

Nov. 22, 1963

Payne wasn’t at Dealey Plaza but was taking reports on the rewrite desk at the Times Herald.

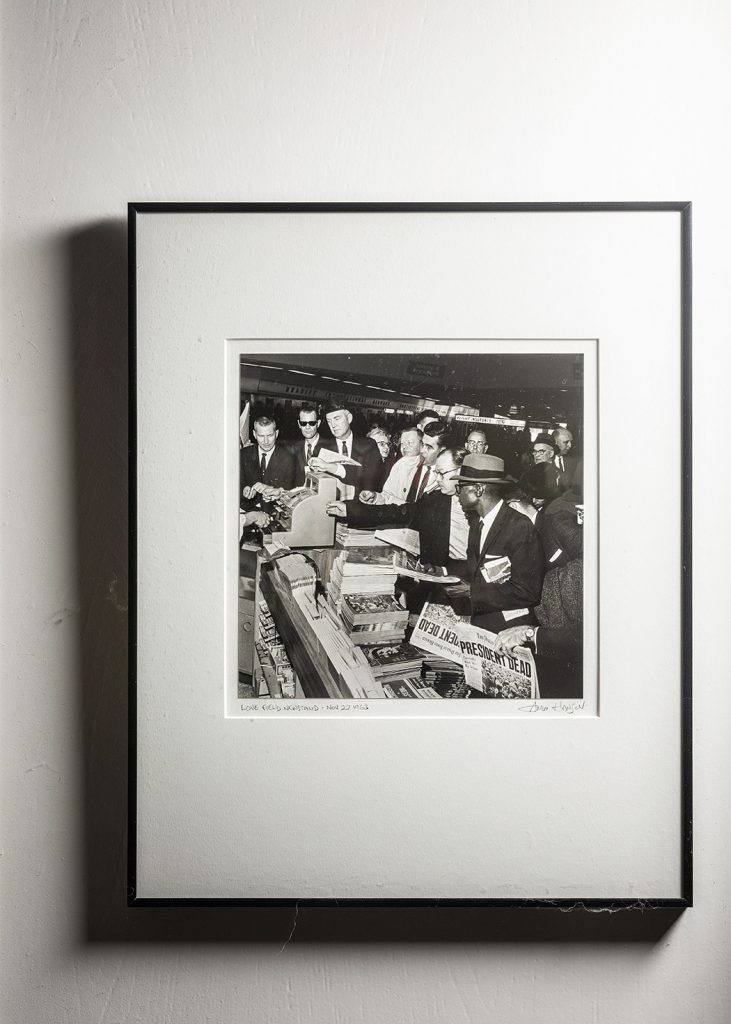

“I was going to do a color story based on what two women reporters were going to tell me. One at Love Field was going to tell me about Jackie — what she was wearing and how she interacted with the crowd. We were past deadline — the Times Herald was Dallas’ afternoon newspaper, and the president’s arrival time at Love Field was about 11:30, so we were holding up the presses. I had taken notes from Val Imm, the society editor who described Jackie’s pink suit, and I was waiting for Connie Watson at Dealey Plaza to tell me what happened there. I was having trouble coming up with a [lead sentence].

“Our city editor and our city reporter were closely monitoring the police radio. They said, ‘Code 3 Dealey Plaza’ which indicated sending police with lights and sirens. When I heard, ‘The president’s been hit,’ I wondered ‘What with?’ I thought of Adlai Stevenson being hit with that sign.”

Payne and Paul Rosenfield, editor of the Herald’s Sunday Magazine ran four blocks to Dealey Plaza.

“It was terrific bedlam there — people not knowing what had happened, and many who saw him hit, of course. I started interviewing eyewitnesses and found several women who said, ‘Our boss took pictures, he was filming. We’ll lead you to him. He’s in the next building.’”

The women took Payne next door to the Dal-Tex Building, where Abraham Zapruder owned and operated Jennifer Juniors, a clothing manufacturing firm.

“Zapruder was frequently in tears. His camera was sitting on top of a filing cabinet in his outer office, and he had the TV set going. I talked to him and tried to get him to go to the Times Herald office to get it developed. I had no idea how good it would be.

“We were watching TV and we heard Walter Cronkite say, ‘The president has been shot, perhaps fatally.’ Zapruder said, ‘No, he’s dead. I was watching through my viewfinder. I saw his head explode like a firecracker.’”

Payne may have been a cub reporter, but he was a dogged negotiator. He stayed at Zapruder’s office for 45 minutes trying to secure the video, but Zapruder wanted to give it to the FBI or the Secret Service instead.

“I called the Times Herald office and said, ‘Get me Chambers, this man has film.’ James F. Chambers Jr., publisher of the Herald came to the telephone – I’d never met him, I’d only been there a few months. I suggested he send a car with Dallas Times Herald on the side so Zapruder would feel comfortable and also offer to pay him, but Chambers was noncommittal.

- Photo cred: Danny Fulgencio

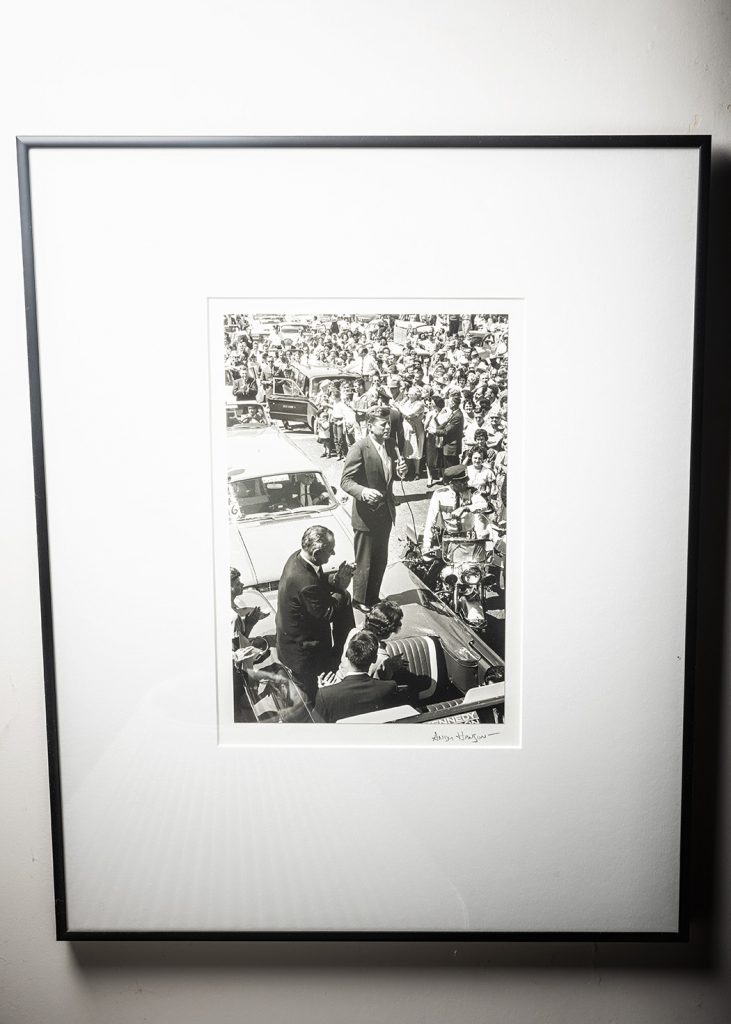

- Photo cred: Danny Fulgencio

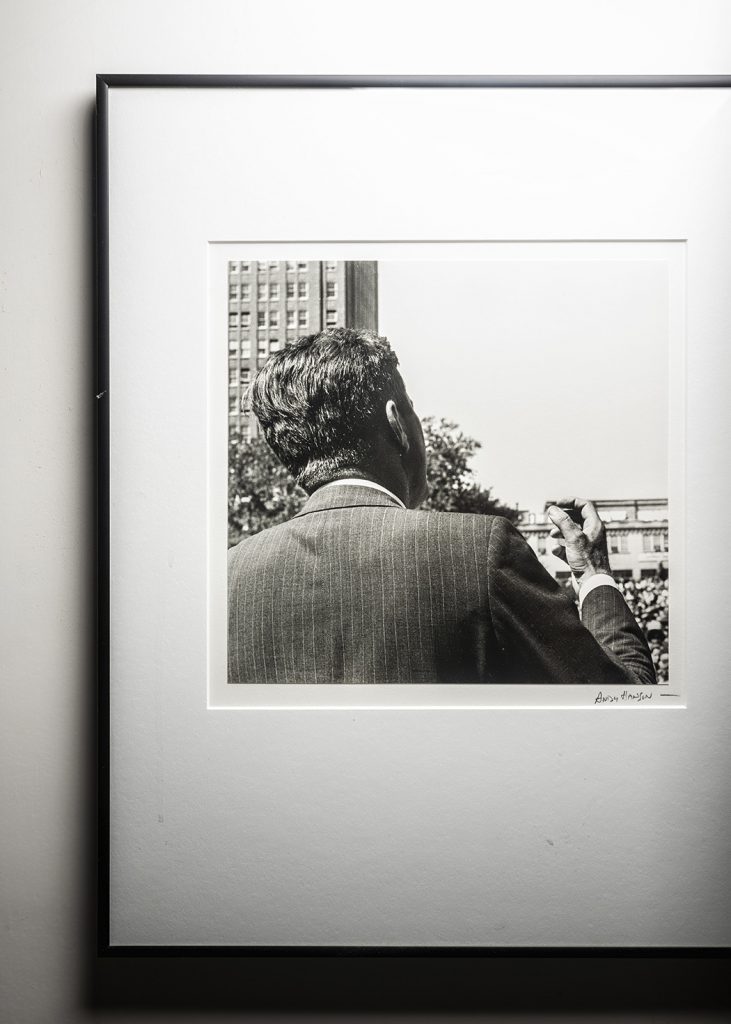

- Photo cred: Danny Fulgencio

Competing for Zapruder film

Soon, three or four men from the FBI and Secret Service showed up with veteran Dallas Morning News reporter Harry McCormick.

“Harry was legendary. He’d covered Bonnie and Clyde, and when he had a secret lead on their location, he didn’t think anyone would believe him, so he got Clyde to put his hands on the windshield to collect fingerprints to prove it.”

When the men all began walking into a private room, they blocked Payne from entering.

“I said, ‘There’s Harry McCormick of the Dallas Morning News, and I’m with the Times Herald. If he’s in there, I’ve got to be in there, so they kicked McCormick out. Then they took Zapruder down to Kodak to have his film developed.”

Payne went back to the Texas School Book Depository and interviewed more people. Amazingly by today’s crime investigation standards, he was allowed to walk through the building and tour the sniper’s nest on the sixth floor.

J.D. TippIt and ‘O.H. Lee’

“[Reporters] John Schoellkopf and Joe Sherman were saying they heard a policeman had been shot in Oak Cliff, but I didn’t want to go out there. I wanted to stay where the action was. I didn’t connect the police shooting with the assassination.”

Later in the day, Times Herald city editor Ken Smart got a lead on the killer’s address and sent Payne to 1026 N. Beckley to gather information on the assassin, known to his neighbors as O.H. Lee.

“It was a rooming house, and I spoke to roomers staying there and to the manager and the owner and her husband. They described him as a standoffish sort of person who got on the telephone and spoke in a foreign language — they thought it was German or Russian. They didn’t know who he was talking to, but it must have been Marina [his Russian-born wife.] They said he didn’t mix and mingle with the rest of them in the evening when they watched TV in the living room during the six weeks he was there. On the radio, I later heard he’d been identified as Lee Harvey Oswald, and he’d spent time in Russia.”

Back in the newsroom

By the time Payne returned to the Times Herald offices, it was dark and reporters were busy working on the Saturday edition.

“Dick Hitt was a prized columnist at the time, and he was going to do the main story on Oswald, but they gave it to me because of all the info I had. I worked until very late and expected to see my byline, but when the first editions came off the press, my story on page one didn’t have a byline. When Ken Smart saw that, he put my byline in, so later editions have it, but microfilm copies do not.”

Saturday was Payne’s regular day to cover the police station, and he was there with a gaggle of journalists when Oswald was brought in for questioning. Only two reporters were still there at midnight when they heard police might have an eyewitness who could identify Oswald as the assassin.

“We needed to confirm it, but [Dallas Police Chief Jesse] Curry had already gone home for the night. It was 1 a.m., and I hated to call him at home after all he had been through, but it was getting close to our deadline. His wife answered the phone, and she was obviously sound asleep. She handed him the phone and he was too asleep to comprehend what I was saying. I tried to take notes, but they made no sense.”

In the end, rumors of an eyewitness turned out to be untrue.

Payne went on to earn a master’s degree from SMU and a PhD in American Civilization from the University of Texas, to write biographies and histories about people and subjects in Texas and to teach journalism for 30 years at SMU. Many of his students never knew about his close connection to the assassination of JFK because he rarely mentions it if he isn’t asked. But he still remembers after 56 years.

“I recall, as I stood in Zapruder’s office looking out onto Dealey Plaza, feeling depressed. I really liked Kennedy. It was painful. I knew it was a huge moment in history I was participating in.”