Hamilton Park agents didn’t approve Dymris McGregor and her then-husband Jimmy Johnson’s application to buy a home the first time they applied in 1959. At only 20 years old, McGregor didn’t meet the minimum age requirement.

“I was so worried they were going to build them all, and I wasn’t going to get any,” she says.

The day of her 21st birthday, the couple drove to a small office at the intersection of Schroeder Road and Campanella Drive. They perused five floorplans before choosing a three-bedroom model on the last available lot on Glen Regal Drive.

“For most of us, this was the first house we ever owned,” she says. “We were so proud. We worked so hard and saved our own money. To be able to buy your own house was a dream come true.”

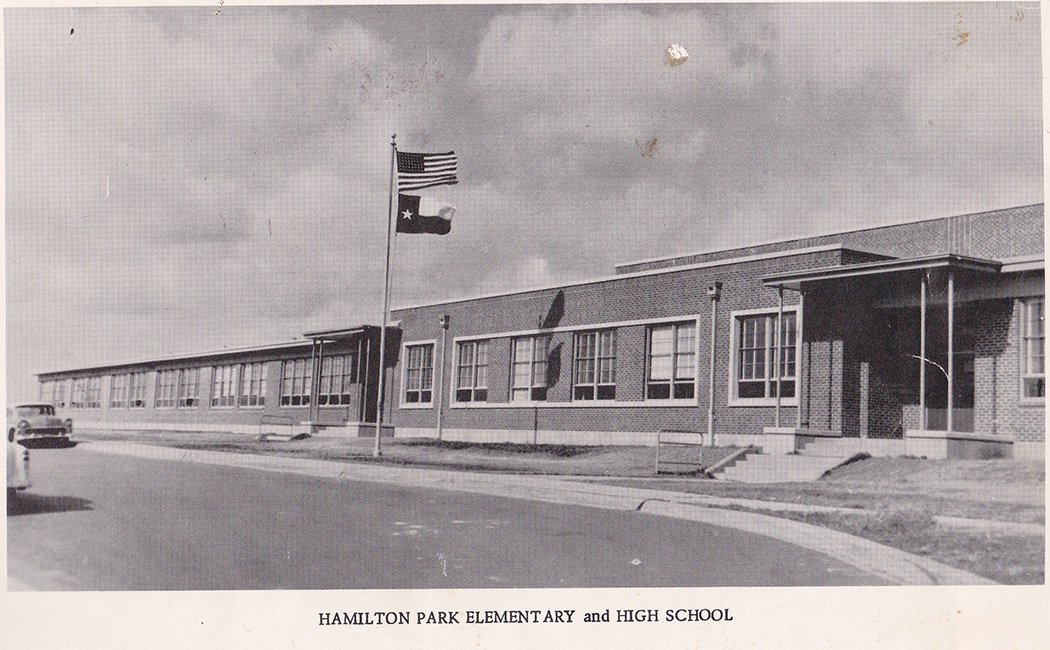

Named after Dr. Richard T. Hamilton, a prominent African American physician, the neighborhood was Dallas’ first planned black subdivision. The Dallas Interracial Committee and the Dallas Negro Chamber of Commerce (now the Dallas Black Chamber of Commerce) created a joint committee to establish the neighborhood.

The growing African American population in the 1940s was squeezed into a handful of residential developments, including Bonton in South Dallas, a predominately white neighborhood at the time. The white residents were hostile to their new neighbors, and a bomb campaign targeting blacks soon emerged — with projectiles thrown from cars and porches and onto roofs of black family homes. The neighborhood often was referred to as “Bombtown.”

Hamilton Park’s creation was two-fold. It solved the black housing crisis, but it also kept families from moving into white neighborhoods.

For Hamilton Park’s residents, the subdivision was a piece of the American Dream, historian William H. Wilson wrote in “Hamilton Park: A Planned Black Community in Dallas.”

The neighborhood marked “the dawn of a new day in Dallas,” former Mayor R.L. Thornton announced at its 1954 dedication, according to Dallas Morning News archives. Five developers sold about 750 houses. The 179-acre neighborhood also featured a shopping center with a grocery store, radio shop, drugstore and beauty salon, as well as three churches.

Hamilton Park’s primary source of pride was its school, which served elementary, junior high and high school students.

Although the school had fewer resources than its white counterparts, the school felt like a family. Students didn’t call teachers Mr. or Mrs.; they called them “Aunty” or “Uncle.”

But the lifespan of the school at Hamilton Park was short. The same year Dallas applauded its own efforts to provide black families with segregated housing, the United States Supreme Court ruled segregation in schools was unconstitutional.

Richardson ISD ignored the Brown vs. Board of Education ruling until the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) guidelines were put into action. Racial attendance zones were banned entirely. Because Hamilton Park was the only black school within the district, students were separated, even within their own families, and sent to schools throughout RISD.

The district considered shuttering Hamilton Park entirely, but neighbors fought back, Curtis Smith says. He served on a biracial committee tasked with desegregation.

“Being in it and being more or less neutral, my job was to desegregate the school district and have a school district at the same time,” he says.

Instead, in 1969, the high school closed, and students were sent to Richardson and Lake Highlands high schools. The junior high shuttered the following year. In 1975, Hamilton Park transformed into Hamilton Park Pacesetter Magnet, a school whose student body was required to be 50 percent white and 50 percent black.

“They moved all the black teachers out of the black school. … They made it a school that has everything so white people would drive over and bring their kids here,” longtime neighbor Ladell Jernigan says.

“They did enough to pacify the federal government.”

As Hamilton Park residents reflect on the school’s closure, they recognize that, in some ways, desegregation’s effects contradicted its intent to treat all students equally. The plan not only curtailed the school but unraveled the tight-knit neighborhood. Families stopped attending football games and activities together. Children weren’t close to their neighbors because they no longer went to school together.

Now, 50 years later, Hamilton Park is once again at the center of discussions about race and education. Former school board member David Tyson filed a 2018 lawsuit stating RISD’s at-large school board violated the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

RISD settled the lawsuit with Tyson in January, and now two minority-majority districts will elect a representative from Hamilton Park for the first time in the district’s history.

“We’ve had ups, and we’ve had downs. … This is the best ‘up’ that I could ever see, and I’m so glad to be a part of it,” Hamilton Park civic leader Thomas Jefferson said during January’s community meeting.

As the effects of desegregation linger, we asked longtime neighbors to reflect on the process — what was lost, what was gained, and what could’ve been done differently.

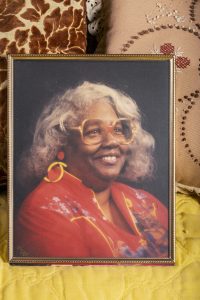

Dymris McGregor

Photo by Danny Fulgencio.

The day that Dymris McGregor bought her house on Glen Regal Drive, she told her then-husband, Jimmy, that she was never leaving.

“I meant it, and I still mean it,” she says.

Now 85, McGregor never moved from the yellow three-bedroom house that the couple bought in 1959. McGregor met Jimmy at a high school football game in South Dallas. They married when he returned from the U.S. Air Force. They later split, and she fell in love with Willie McGregor, who had two children of his own. They married in 1963 and raised the boys on Glen Regal Drive.

Dymris McGregor started her career as an assistant at James Madison High School before becoming a secretary at Hamilton Park school. When the court order came down, she was sent to Lake Highlands Junior High to work in the attendance office. She retired a decade later.

McGregor made lifelong friends with her Lake Highlands coworkers — who ensured she was included — but her sons were separated, bullied and ostracized by their peers. Hamilton Park families stopped meeting for football games and attending school events together. For McGregor, the loss of camaraderie was the biggest consequence of the school closure.

“I knew all the kids because all of them lived right out here. Where Medical City is, there used to be houses. Everybody knew everybody. You didn’t have to worry about your children. It was interesting because if some parents had to work late, all they had to do is call. ‘Dymris, I have to work late tonight. Can you take so and so until I get home?’ I’d say, ‘Yeah.’ We always looked out for each other.

I was there until they integrated. Then, they sent me to Lake Highlands Junior High. When I went there, they had no black kids, no black teachers. There was nothing in that school black but me.

I didn’t even know where Lake Highlands Junior High was. When they sent the letter telling me where I was going, I had to get in my car and go find it. When I went over there, everybody over there did not know I was a black lady.

I lucked out because the principal and the kids and the people all accepted me. It was not hard for me. But a lot of my friends did not fare well. Their kids didn’t either. I will not lie about that.

Ever since I’ve remembered, the four girls who work in the office gave me a birthday party. I retired, and they were still working. We’d meet once a month for lunch. They would always pick somewhere I’d never been and places I shouldn’t have been. Whatever was going on, they included me and made sure I went with them. I was never excluded.

[Desegregation] really surprised us. We had heard it was coming. We just never figured RISD would do it because they never had anybody black here but us.

I cried a lot because my kids would come home, and they didn’t want to go back. It soon got better, but it was not good. When you’ve grown up a certain way and were treated a certain way, you were never made to feel that you weren’t good enough, you weren’t smart enough. They didn’t have any good friends when the going got tough. It was a whole new adjustment for the kids and the parents. You had to worry about your kids getting on the bus. Then if the bus didn’t pick them up, you’re at work and your kids are at the corner waiting on someone who may not show.

They would say ugly things to them. They’d go to sit down and pull the chair out from under them and call them names. It just was not a very good environment.

I was so glad when they graduated. I probably was the loudest of any parent in there. And I said, ‘Thank you, God. They didn’t kill my kids.’”

Photo by Danny Fulgencio.

Patricia Price Hicks

Patricia Price Hicks smiles as she remembers the cake walk at Hamilton Park Elementary School’s carnival. She loved school even though it was rigorous. Hicks grew up in Hamilton Park with her mother, Delores, father, Robert Earl Price, and two siblings. The namesake of the Forest Lane post office, her father was pastor of New Mount Zion Baptist Church and worked for Lomas and Nettleton Mortgage Banking Corporation.

When Hicks was a fourth-grader in 1969, Richardson ISD desegregated its high schools. Hamilton Park High School shuttered, and its students were sent to Richardson and Lake Highlands high schools. One year later, U.S. District Judge William M. Taylor demanded that the junior high also close.

Taylor’s order came down at 6:30 p.m. Monday, according to the Dallas Morning News archives. By Tuesday at 8:30 a.m., 250 students gathered at the school’s auditorium before they were bussed to three RISD junior highs — Forest Meadow, Northwood and Lake Highlands. The process felt hurried, with both students and parents unsure of what school students would attend. Hicks began junior high at Forest Meadow in 1971.

Now a 30-year teacher and member of the Dallas County Historical Commission who secured a historical marker for the school that is now Hamilton Park Pacesetter Magnet, Hicks says the transition affected students’ identities and self-worth.

“A lot of the parents did not find out until the last minute that their children were going to be bussed out, particularly when the junior high school was closed. That was ’70. I went to Forest Meadow in 1971. They didn’t know that they were going that first year to Forest Meadow. When they went to Hamilton Park school, they found out. They put them on busses. One girl told me there was an announcement made as they got off the bus, and they were walking into the school. They said, ‘They are here.’

The white students were already sitting in classrooms in their seats when the black students were bussed over to Forest Meadow. Here’s a culture shock for us. We’d been exposed in shopping centers and stores and libraries, but we’d never been in a classroom setting with white students.

What they did is send Clayton Bell, who was at Hamilton Park, as an assistant principal to Forest Meadow. They sent Frances Money. Ms. Money had worked at Hamilton Park for a short time in the home economics department. That was it.

They did not send any math teachers, any English teachers. That’s what I was needing. I needed a role model. I didn’t have them at Forest Meadow. I didn’t have them at Lake Highlands. We were having to maneuver on our own and then go home and complain to our parents. We depended on our parents to do whatever they could to help us.

Some chose not to go. Their parents chose to transfer them out, in other words, to other Dallas ISD schools instead of Richardson. They did not want them going to white schools.

The teachers at Hamilton Park, they protected us. They were very nurturing, very loving. They were strict, and they would call our parents. At Forest Meadow, the people didn’t know our parents, didn’t care if they knew our parents or not.

It tore down self-esteem. It tore down self-worth because people were insensitive to our customs and our culture. We were like guinea pigs. You understand? It’s like you’re in a test tube, and somebody’s experimenting. That’s how I saw us. The teachers did not know how to teach us. They knew nothing about African American history. And so when they taught it, they taught it in a very negative manner. When I say that, I can distinctly remember one of my teachers. She is deceased now. She said African Americans had big lips. They had big ears, they had babies, they had Cadillacs, and they did not have garages to put the Cadillacs in. Sitting in a classroom and having to listen to this nonsense, I didn’t know people who she was referring to. Who do you turn to? In Hamilton Park, that was not the case. I’ll never forget it.

In the ’60s and ’70s, the teachers did a lot of lecturing. But they really needed to be sympathetic and try to guide us. There was not a lot of guidance from counselors. They didn’t tell you what subjects you really needed to take. After you finished a year, they tried to tell you what you should’ve taken. When it came time for me to graduate, I didn’t take any foreign language, and I should have. Had I known, I would’ve taken extra math, extra science. We were thrust into this new way of schooling. There was fear and frustration.

I learned you grow from all these hurdles. You learn to maneuver your way. I’ve had to applaud myself for my successes.”