On Sunday afternoon, Oct. 11, 2015, Zoe Hastings was on her way to church for a class about becoming a missionary. While returning a movie to a pharmacy at Garland and Peavy, she went missing. When she didn’t show up for her class, friends and family began to search for the Booker T. Washington theater student. After staying up all night trying to get hold of her, Hastings’ parents tracked her phone to Dixon Branch near Lochwood. When they arrived, a crowd had gathered and police were taping off the crime scene. Their worst nightmare came true. Her body and the family vehicle were found down a ravine. She had been sexually assaulted, stabbed and left in the creek bed.

How do parents respond to the loss none should have to experience? How does a best friend progress through life while remembering and honoring her lost companion? How does family support the parents while dealing with their own grief?

Nearly three years after Zoe’s death, the life she led and the impact she had on the people around her is evident each day, a living testament to a life cut too short.

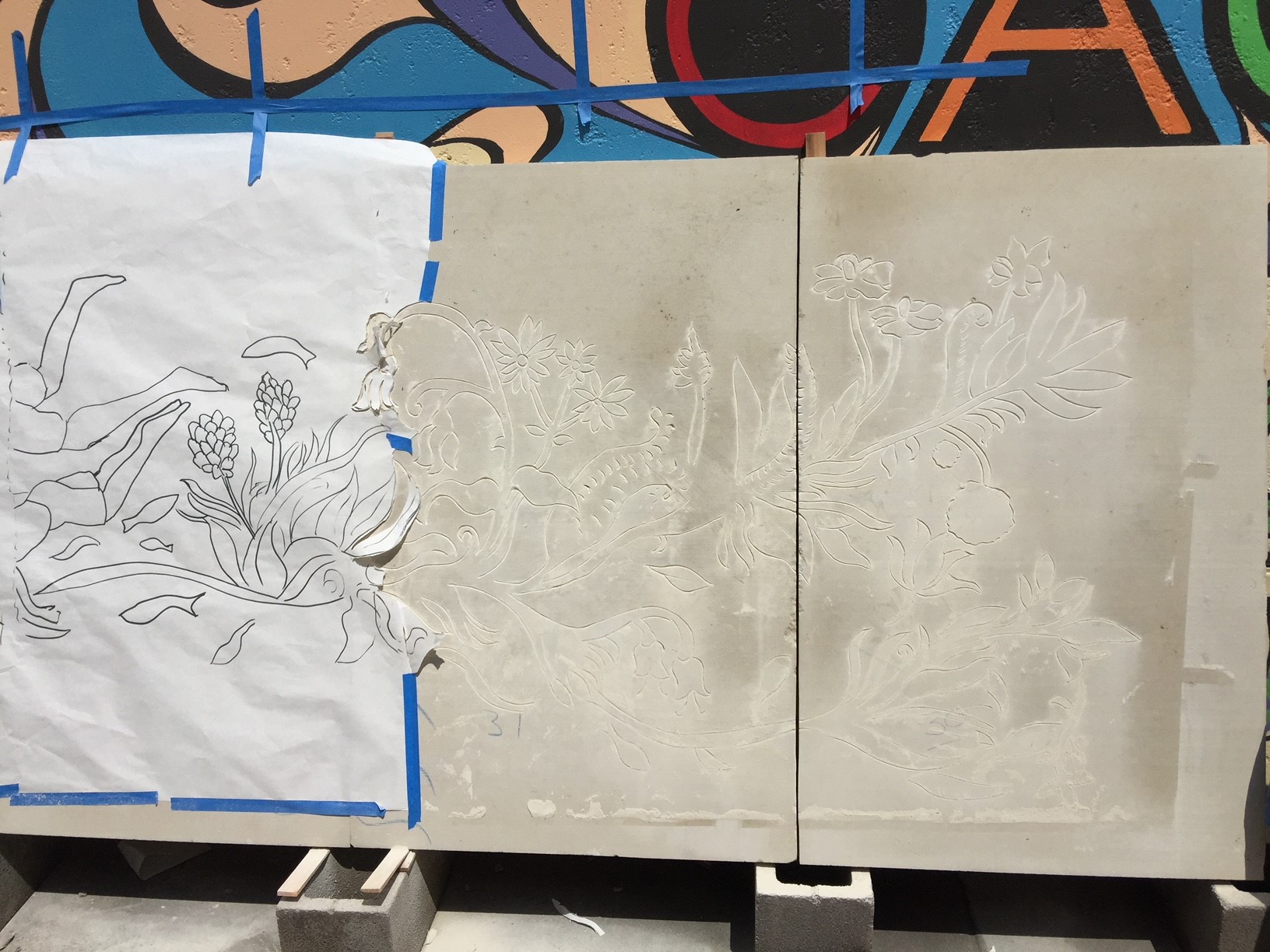

Jim Hastings is creating artwork for White Rock YMCA in honor of his daughter, Zoe (Photography courtesy of Allison Albitz).

Father Jim Hastings:

Drawing through pain

When Zoe died, Jim Hastings had been appointed as bishop of their church. He helped balance the budget, sat up front and taught during services, and he spent one night a week at the 500-member church helping others work through their problems.

“If I had nothing to do, it would have been terrible,” he says. “It took me out of what I was dealing with to know there are other things happening in the world.”

But he couldn’t continue helping others without finding a way to deal with his own emotions. After Zoe died, her father decided to draw every day. He is an art teacher at Merriman Park Elementary in Lake Highlands, and he has painted murals all over Dallas and illustrated several books.

He committed to drawing a picture of one of his family members every day. The other Hastings children are Hannah, 18, Tristan, 15, Ruby, 11, and Olive, 5.

Since then he has made more than 900 drawings of family members, all in simple ballpoint pen, but the emotional range and power of the drawings (which can be found on Instagram @jhastings40) is captivating.

He kept the practice up when his mother was diagnosed with cancer last year, sketching her each day until she died six weeks later. His father had died a few months before Zoe.

Drawing helped Jim realize how much he still has left, and it inspired him to make sure he uses his time productively.

“I see drawings, and they take me to a certain point in life,” he says. “They definitely helped me focus any anxiety, nervousness, worry or whatever. Life doesn’t stop. It was a way for me to keep moving forward. If I didn’t start making pictures I might stop completely.”

Mother Cheryl Hastings:

Nursing through recovery

Cheryl Hastings put her education on hold to have a family, and she became a nurse after the birth of her third child.

She works in labor and delivery at Parkland hospital and was on her way to getting a master’s degree to be a midwife when Zoe was murdered.

In her grief, Cheryl found a new purpose.

She saw an advertisement about the need for sexual assault nurse examiners. With additional training, nurses can examine women who’ve been sexually assaulted, preserving evidence for trial. They could even testify as expert witnesses.

For a mother whose daughter was sexually assaulted before she was murdered, this was an interesting choice. Cheryl says she even surprised herself a bit.

“I thought, ‘I don’t want to do that. Well maybe I do want to do that,’ ” she says.

The role is an important but undesirable one, requiring a balancing act of attention to detail, empathy and emotional distance.

“These people need someone who can help them in that step to recovery,” Cheryl says. “A little voice inside me said try it. They could use you.”

Comforted by community

Nick Hastings saw Zoe almost weekly growing up. He says she was the first one to jump up and give you a hug but also the one to ask how you were doing, a maturity and selflessness beyond her years.

Through Sunday dinners and babysitting his children, Nick got to know Zoe as a young woman who was excited for life. Nick wanted his children to be around Zoe, knowing her authentic generosity of spirit would rub off on them.

When his niece died, Nick was part of the team that canvassed the neighborhood in hopes of finding Zoe’s killer. He was astounded when 300 people showed up to help. Nick lives in the neighborhood as well, and he says he was shocked that something so violent could happen in what he considers a safe place, especially in broad daylight.

Nick says he became a bit more diligent about watching out, more skeptical, perhaps a little less trusting of the world around him. He had conversations with his kids about engaging strangers and being aware of their surroundings.

While it was a trying time, Nick also learned to experience life a bit more deeply.

“It’s not necessarily what you want to tell your kids, but we realized that life is short,” he says. “Enjoy as much time as you have with people.”

Nick feels that Zoe’s murder brought the family together and made them trust in their faith.

“Although we don’t understand everything, we have faith that God is there,” he says. “We spend a few more minutes on our knees thanking God for the time we have.”

Friend Beppy Gietema:

Holding on to Zoe

When Beppy Gietema graduated from Booker T., she and Zoe took a three-week trip to the Netherlands. The two friends listened to music and danced in the aisles of the plane while everyone was asleep, setting the tone for an eventful trip.

Spontaneity and joy drew Beppy to Zoe in the first place. They went to renaissance fairs and made movies together, listened to reggae on the way to Torchy’s Tacos and left googly eyes on hot sauce bottles.

Beppy, who attends the Savannah College of Art and Design, started getting calls and text messages the day Zoe went missing. Finally she got ahold of Zoe’s mom, who told her that her best friend was dead.

“The words will never leave me,” she says. “They are crisp in my mind.”

When she learned of Zoe’s death, Beppy cut off her ponytail, which she keeps in a box of letters and pictures of the two of them. Zoe’s death crushed Beppy’s spirit.

“She was the first person that I lost that I really loved,” she says. “I lost half of myself.”

Beppy is off at college, but moving on from the memory of her friend is not something she wants to do.

“I don’t know how you can move on. I don’t want to leave her in my past. I want to bring her with me wherever I can.”