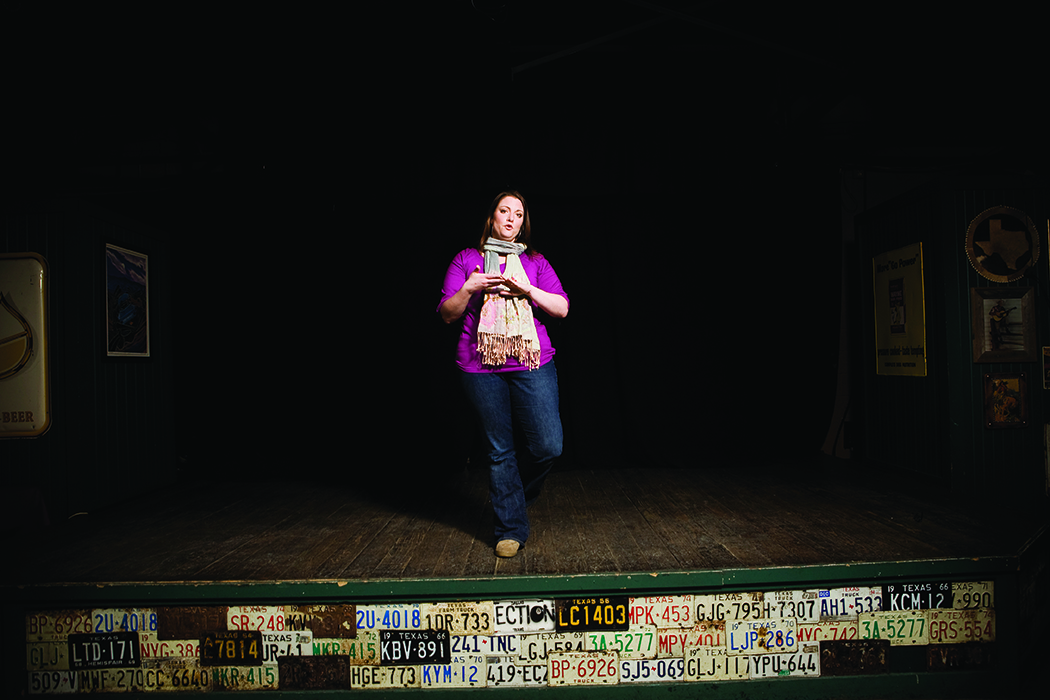

Sharon Flatte, a White Rock-area homeowner, represents women’s significant roles in Deep Ellum’s revitalization. (Photos by Danny Fulgencio).

In the early 1990s, White Rock resident Sharon Flatte was an eager young artist. Accompanied by an inked-up guy (her human portfolio, if you will), she walked into Tigger’s, Dallas’ first mainstream tattoo parlor, and asked Mark “Tigger” Liddell, for a job.

“I don’t hire girls,” the shop owner told her.

None of them knew she would own the place a few years later.

She’d grown up in Amarillo, Texas, with five brothers and few resources. She barely graduated from high school; a counselor figured administrative work was the pretty students’ lot and placed her in secretarial classes. But Flatte possessed talent and smarts beyond shorthand and typing. And she was resourceful.

She hightailed it out of Tigger’s and found Alice’s Asylum, an underground, bare-bones operation.

“It was freestyle, guys tattooing with their shirts off,” she recalls. “There was no air-conditioning, and they were really serious.”

Sharon Flatte (Photo by Danny Fulgencio)

That’s where she met her husband and business partner, Jimmy Flatte. In 1994 they opened Taboo Tattoo, a few doors down from Tigger’s.

They bought Tigger’s next.

“[Liddell] had been living over the shop, and the first thing I did was rent a dumpster and start gutting the place,” Flatte says. She’s since transformed the upstairs into sterile-meets-hip workspaces for her artists. Downstairs imitates an art gallery, one specializing in voluptuous, sword-wielding nudes.

Over the next few years they acquired shops in Dallas, New Orleans and Oklahoma. Sharon soaked up business acumen from Jimmy and others she admired. But when her husband died, everything changed.

“Cancer,” she says. “Jimmy died 12 years ago.”

A dark time ensued.

“We had built everything together,” she says.

Deep Ellum, the effervescent area she so adored, was dying, too. Throughout the once vibrant district, businesses shuttered until almost nothing remained. Flatte’s son Cody Biggs, a celebrated artist in his own right, who had been running one of her shops in Oak Cliff, suffered a serious motorcycle accident and couldn’t work. After a long battle aided by his personal injury attorney, compensation and support has been won. Now at least the basics are covered.

An acquaintance from Los Angeles — “a big huge name in the business”— offered to help, came to Texas and told Sharon he’d take care of things while she “recovered.” She says it was “clear from the get-go he just wanted me out of the picture … His old-school way was not my way, so I fired him.”

He did not take it well. Things heated up until Flatte, donning her favorite thigh-high platforms, says she kicked him so hard he slid across the floor.

Ever pragmatic, she made the strategic decision to streamline, selling every studio except Taboo and Tigger’s.

Whitney Barlow, along with spouse, Clint, revived Trees, Bomb Factory and Canton Hall. (Photo by Benjamin Hager).

Art, music, wine

Frank Campagna, the charismatic owner of Kettle Art Gallery rattles off names: “Rebecca [Bogart] at La Reunion, Lauren [Levin] at Urban Paws, Kathleen [Evett] Upper Paw, Giselle [Ruggeberg] at Jade & Clover, Paula Lambert at Mozzarella Cheese Company, Susan Reese of Madison Partners: Women running the show in Deep Ellum.”

With Kettle Art Gallery as her home base, White Rock-area resident Paula Harris founded Discover Deep Ellum and Wine Walks, where tourists buy a local-art enameled wine glass before visiting various venues.

“Jade & Clover took the neighborhood by storm,” Harris says. “People come in the gallery just looking for Giselle’s store.’’ Harris is dropping names where Campagna left off. Catherine Jacobus at Stonedeck (Lake Highlands resident), Whitney Barlow who, with husband, Clint, re-opened Trees, The Bomb Factory and Canton Hall.

“Whitney,” Clint told us a few years ago, “she’s the one you need to talk to.”

Of her first look at Trees, Whitney recalls, “It was a disaster. Five years’ worth of water damage. You could see sky through the ceiling. There were roaches on the floor. I said, ‘This is awesome’. I think Clint thought I would say, ‘No way,’ but there was just a great vibe.”

The re-opening of Trees in 2011 kicked off a renaissance of Deep Ellum, according to the late Barry Annino, former Deep Ellum Association president. “Once they opened, people got excited and wanted to be around them. They are pioneering the comeback of Deep Ellum.”

Barlow doesn’t see it that way, because so many are working to nurture the venue and the neighborhood.

“We couldn’t be successful if we acted like we knew it all, like we could do it all ourselves,” she says.

Like Tigger’s, the Barlows’ concert halls have preserved the ambience of the past, but all have matured.

Consider Lake Highlands’ Amanda Austin, who, against the odds, made a success of Dallas Comedy House on Main, then fought off developers to keep her space from becoming a barbecue joint.

“We need people around us,” Barlow says, “and we are not afraid to ask for help.”

Amanda Austin (Photo by Sean McGinty).