Wallace Elementary teacher Juna Saw, a Burmese native, moved to a refugee camp at age 8. She lived in the camp for years prior to emigrating to America at 24. Last spring break Saw decided to visit her homeland, and she asked two teacher friends and Wallace principal Debbie Yarger to come along. Maybe what they saw would help them understand problems faced by a growing number of refugees in Lake Highlands schools, Saw says.

The women visited the Mae La refugee camp where Saw grew up. The camp is surrounded by gates and barbed wire. About 40,000 people live there; pigs and chickens running wild eventually serve as food.

Most refugees stay in the camp because it’s their only opportunity to obtain an education for their children.

“The trip really opened my eyes to my students’ life experiences before they walk into Wallace,” teacher Ashley Nick says.

Children living in Burmese refugee camp.

“The kids [in the camps] are happy. Their life is very simple. Do they have all the things that we have? Absolutely not. They don’t have electricity. They don’t have running water. They don’t have flushing toilets. They don’t have a lot of materials in the schools. It’s just different,” Yarger says.

Carmen Casamayor-Ryan, who oversees Richardson ISD’s Newcomer Center that helps refugees adapt to new surroundings, says stories like this help personalize the hot-button issues of immigration and refugee resettlement.

“Every day here, you connect with them, and you are in awe,” she says. “I have the filter of good experience every time I hear a negative news story.”

More than stats

Refugee resettlement in the United States and Texas, by and large, is unprecedented and contentious.

“We are witnessing the highest levels of displacement on record,” states the United Nations Refugee Agency. The White House plans to accept 110,000 refugees from around the world in fiscal 2017 — that’s 30 percent more than 2016’s 70,000.

Texas from October 2015 to October 2016 resettled more than 7,200 refugees, according to federal records.

Dallas Mayor Mike Rawlings has said Dallas will embrace refugees, while Texas Governor Greg Abbott promised to withdraw our state from the United Nations Refugee Resettlement program.

Federal officials have responded that refugees, who undergo stringent security screenings, will continue to resettle in Texas through federal programs.

Maybe you align with the open-arms style of Rawlings or side with Abbott’s plan to prevent refuge in our state. Perhaps you fall somewhere in the middle, or just don’t know anymore.

But your status as a Lake Highlands resident means odds are good that the matter is neither obscure nor remote — for us, refugees and asylum seekers have familiar faces and names.

You probably work, study, worship, volunteer alongside or send your children to school with those who have fled Burma, Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Ethiopia, Venezuela, El Salvador and other war-, poverty- and violence-embroiled countries.

We are witnessing the highest levels of displacement on record.

This month, meet some of these refugees, and learn about what brought them to the United States and how people in our neighborhood are helping them chart a new life.

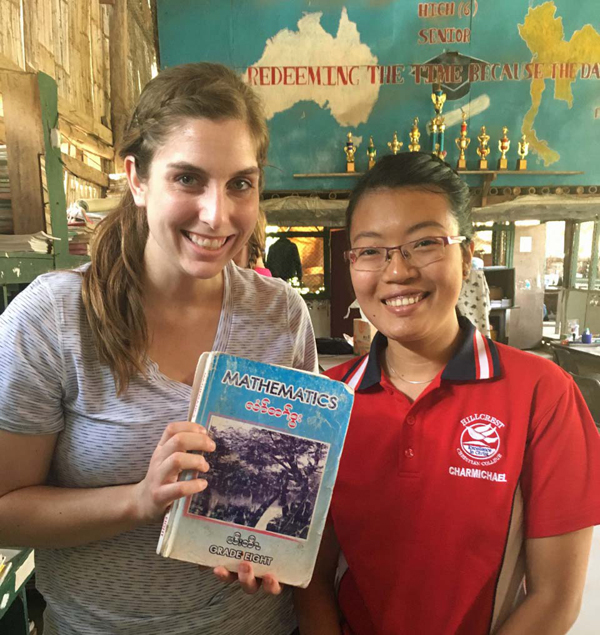

Wallace Elementary educators — teacher Ashley Nick, principal Debbie Yarger, ESL teacher aide Juna Saw and teacher Diane Royer — visited a large refugee camp in Mae La, Thailand, near the Burma/Myanmar border.

Forced to flee Afghanistan after working for the U.S. Army

Mohammad Haroon Anwayi grew up in a Taliban-terrorized area.

“They used religion only as a cover, but their actions were in no way related to our [Muslim] religion. Their violence has nothing to do with religion.”

He witnessed destruction, killing of civilians and government workers for no reason; he saw women confined to the home and girls denied school.

In 2001, American and Afghan military started working together to make things right, as he saw it, for his countrymen.

In 2008, when he graduated from high school, where he had learned basic English, he wanted to do something important, he says.

He applied for a job as a translator for the U.S. Army. The Army added him to the Provincial Reconstruction Team (PRT), a U.S. government unit working in war-torn and politically unstable states. Later, he became a cultural advisor.

“This was never a safe job,” Mohammad says. “It was war. A lot of people, a lot of translators, died.”

Stationed in the South Province, where the Taliban was still powerful, violence steadily increased, he says. His parents, three brothers and four sisters feared for him.

He sympathized but was certain he was taking the righteous path, he says.

“I knew I was on the good side. We are trying to get stuff straight and establish government in the country,” he says. “I was seeing the threat, and I knew only one way to fight it was to establish a rule of law. That is what I was trying, with the team, until the last moment of opportunity.”

If your hands were soft and clean, they assumed you worked for the U.S. government, and they would kill you.

Mohammad’s wife, Maghfera, is a wide-eyed, soft-spoken, frequently smiling and impeccably polite young woman from his hometown. Like his family, she urged him to return to the safer capital. But he knew the PRT was slated to disband in 2014 and he intended to stick with it to the end.

Staying alive that long would prove difficult, he says.

Not only did he see many of his team members — both Afghanis and American soldiers — suffer casualties and death, but each time he traveled to see his wife, he risked life and limb.

“We usually traveled in convoys, the safest, though there was the potential of bombs. You could take a flight, not usually available, or taxi — but in taxis you stood a good chance of being pulled over, dragged from your seat and executed.”

The Taliban, the only terrorist group on his radar at the time, had ways of knowing who worked for the Americans, he says. For one thing, word got around in a small town. Or they could drag you out and examine your hands.

“If your hands were soft and clean, they assumed you worked for the U.S. government, and they would kill you.”

Two years before the PRT shuttered, the American military began the process of applying for refugee status for Mohammad.

He hoped to live in Kabul, and he remained there for a couple of months.

“But it was no life. I can’t go anywhere. Can’t even visit my father’s village.”

He could trust his family and closest friends, he says, but as for everyone else, he didn’t know who approved of his efforts and who saw him as a traitor.

Though he spent seven years working, living and entering combat situations with American troops, and though those very Americans launched his refugee resettlement application, Mohammad says he still underwent strict vetting — “examining your work history, background checks,” he says. “I had to take tests, including a polygraph, just to work for the U.S. in the first place.”

And by this time, the couple also had a child, 2-year old Ahmad, whose security was essential.

The family of three resettled through the International Rescue Committee, which has offices in our neighborhood. They were placed in a tiny apartment near Richland College.

Life in America started out depressing, he says, but soon the American soldiers with whom he’d worked in Afghanistan began contacting him — calling, texting and even visiting to see how he was doing.

“With my Army friends coming to visit, it felt good. It reminds you that you were part of a big thing, and that is good.”

And he began working right away — doing what?

“Everything,” he replies with a barely perceptible laugh.

He worked every odd job he could find that matched his skills and wound up working long hours as a mechanic at a body shop. Now, in order to spend more time with his family and to help in-laws moving from Afghanistan to the United States, he’s working as a pizza deliveryman.

He has moved to a bigger apartment in the Lake Highlands area so he can temporarily accommodate his wife’s brother, Abdul, and Abdul’s wife, Shrifa, and their young child, Masi — that family also is part of the UN Refugee Resettlement program.

“When I came, we had no one. We want to give our family something to come to.”

Maghfera, clad in a colorful veil and a dress over black pants, smiles and nods, popping up from the couch to attend to the baby or to deliver a gorgeous tray of fruits and nuts.

With Mohammad translating, she says she is grateful that her family has security and that her brother is here.

“If it was safe, though, I would be home,” she says.

Mohammad turns so he isn’t facing his wife’s sad eyes, or maybe so she doesn’t see his.

“There doesn’t seem like much of a chance of going back.”

Alejandra Valbuena, middle, and other students learn English from volunteers at Pamper Lake Highlands, a nonprofit benefitting local women and children. She takes adult literacy classes three days a week and recently began working at the charity’s childcare center. Photo by Danny Fulgencio

Refuge from lesser-known conflicts

Afghans make up more than 50 percent of the refugees coming to Dallas, according to Anne Marie Weiss-Armush of DFW International, a refugee support network based in our neighborhood. Syrian refugees represent the most recent influx.

Turmoil in Latin countries such as Venezuela also brings asylum seekers to our neighborhood.

A few years ago, Alejandra and Ruben Valbuena were living modestly in Venezuela. Both earned bachelor’s degrees — Ruben was working as a quality assurance engineer at a food-producing factory and his wife wanted to pursue a master’s degree in civil engineering.

After they married, Alejandra says through an interpreter (Yaneth Lopez, a volunteer), the couple planned to have two children. “But now, the situation is different,” she says.

In recent years, an economic crisis and a food and medicine shortage, not to mention suppression of free speech, has made Venezuela a dangerous place to live.

Venezuelans today are given a number and a shopping day — that’s one day every week to 10 days when they are allowed to purchase groceries, medicine and toiletries. But queues at the markets, no matter the day, stretch down streets and wrap around buildings. People begin lining up at 4 a.m. Most shoppers are met with bare shelves by the time they enter the store.

“As Venezuela’s lines have grown longer and more dangerous, they have become not only the stage for everyday life, but a backdrop to death,” the Associated Press recently reported.

Several dozen people have been killed in line during the past 18 months, including a 4-year-old girl caught in gang crossfire.

“An 80-year-old woman was crushed to death when an orderly line of shoppers suddenly turned into a mob of looters — an increasingly common occurrence as Venezuela runs out of just about everything,” the AP reports.

Ruben joined a protest against the government — a decision that changed his life.

“I was seen protesting,” he says through the translator, “and word got back to the factory.”

The first time, his pay was reduced and he was demoted, he says. “We were obligated to support the government.”

The government has taken over formerly worker-controlled factories. As conditions worsened, he feared for his safety.

“Anyone can go and kill you and justice will never be served,” Ruben says.

Alejandra and Ruben Valbuena sit with daughter Alessia, 2, at their Lake Highlands apartments. Photo by Danny Fulgencio

The young couple was surviving, and Alejandra was grateful to be part of a tight-knit family with loving parents.

But Ruben, unable to sit quietly as his country suffered, continued to protest.

In a December 2015 report, the Venezuelan Violence Observatory estimated that 27,875 killings occurred that year. Venezuela now rivals El Salvador as the world’s deadliest country, according to a New York Times article.

When Ruben and Alejandra learned they were going to be parents, they decided to seek asylum, even though it meant leaving behind people they love — among them, Alejandra’s father, who lost his job as a university professor due to his denunciation of Venezuela’s President Nicolás Maduro.

Alejandra is an olive-skinned beauty with long black hair and striking eyes that water when she talks about her family in Venezuela.

“Mal,” she says when asked how it feels to think about her loved ones still there. “Bad.”

Now she has to do best by Alessia — the 2-year-old hops from one toy to another, giggling and clearly content as her mom sits on a couch at the Pamper Lake Highlands charity, which provides services to women including childcare, supplies for babies and English classes.

Alejandra discovered Pamper Lake Highlands, founded by Lake Highlands resident Caren Bright, as she was scouring the city for affordable English classes.

As soon as Alejandra received a permit to work, Bright gave her a job in the day care.

We want to show our daughter hard work. There, hard work was not valued and strong opinion was persecuted …

“She is so beautiful, and we are lucky to have her,” Bright says. “She never misses a day of work.”

Her husband is trying to learn English on his own.

He was cleaning pools for a living, but after breaking his leg while playing soccer (“I love sports,” he says), he works at a check-cashing company.

He says he knows opportunities will increase as he improves his English.

“I don’t want to be a load on this country,” he says. “I feel I want to give back to the country where I will live.”

Ruben says he sold everything they owned to pay someone to help him fill out necessary paperwork to secure political asylum in the United States.

“I don’t care about all of that. She is the most important thing,” he says, referring to his daughter.

The second child they planned for will have to wait, Alejandra says, and her boss, Caren Bright, cries when she overhears this.

“What a sacrifice you have made,” Bright says. “And an intelligent choice.”

Alejandra is just grateful Alessia doesn’t have to go hungry, as so many in Venezuela do.

“[Here] we have milk, food, diapers,” she says. “And if you work hard, you will have a car, house.”

She adds that the freedom to speak your mind here and hold your own opinions is invaluable.

“You are not forced to vote for this politician with a gun to your head,” she says.

When she first arrived, she says she felt isolated and homesick, but as soon as she realized there were so many people here in Lake Highlands going through similar or worse situations, as she came to know other women through PLH’s English classes, she “felt happier and more motivated and comfortable.”

She is determined to learn — “I will not be one of those who lives here and does not learn the language,” she says.

An essential thing one must muster when coming to America as a refugee or asylee? “Humility,” Alejandra says definitively.

You might be a doctor, lawyer or engineer where you came from, and a pool man, check-cashing clerk or day care worker in the United States. You might be viewed as unintelligent if you do not speak the language well, and Ruben and Alejandra both say they can live with that, for now.

Ruben Valbuena at his job. (Photo by Danny Fulgencio)

“We have self-reliance, a marriage at peace, we can sleep at night,” Alejandra says. “We want to show our daughter hard work. There, hard work was not valued and strong opinion was persecuted — so one could not grow. How can you be allowed to grow when they will kill you for thinking or speaking your beliefs, just as they will kill you for a pair of shoes? You cannot grow when you are in constant fear.”

Ruben and Alejandra say they aim to apply the same drive here that earned them honors at their Venezuelan university.

“Even if it takes five more years,” Alejandra says.

To be eligible for asylum in America, people must have fled their home countries in fear of persecution due to race, religion, nationality or politics. Once in the United States, those who apply for asylum may legally stay in the country while their application is evaluated, a process that can take years.

How can you be allowed to grow when they will kill you for thinking or speaking your beliefs, just as they will kill you for a pair of shoes? You cannot grow when you are in constant fear.

It is during this period of limbo that neighborhood nonprofits and churches offer essential services.

When Ruben broke his leg, for example, he went to the QuestCare Clinic, operated by Watermark Church on Skillman at I-635. He gave them a $10 donation, and the doctors there patched him up. Same thing when Alessia bumped her head and needed a couple of stitches. Ruben also attends a group at Watermark where immigrants, refugees, asylees and others get together to help one another with résumés and offer support.

While they are aware of the negative news and political views in Texas related to refugees and immigrants, Ruben and Alejandra say they have felt mostly kindness since arriving in Dallas last year.

“People help each other,” Ruben says.

Alejandra adds that she wants refugees seeking resettlement here to have a chance, because the ones she has met are the most hardworking and grateful people she knows.

“They might be the next doctor to find a cure. They might be a person to make life better. Chances are important.”

Refugees, a subset of second language learners in the Richardson ISD

Richardson ISD’s Newcomer Center ideally is the first education-related stop for all families who speak a language other than English at home; 74 languages recognized by the Texas Administration Agency are spoken at RISD campuses plus an additional 15 other languages/dialects, says Sara Fox, compliance coordinator for second language learners in RISD. Spanish, Arabic, Vietnamese, Amharic and Urdu are the five most spoken this school year.

Accommodating second language learners has been a major priority for the district since 2001, when its Newcomer Center opened.

When enrollment papers indicate that a language other than English is spoken at home, an appointment is scheduled at the Newcomer Center. Experts there evaluate the situation, both for educational and counseling needs, which has become essential with the influx of refugee or asylee students — 1,059 so far this year compared to 1,038 in 2015-2016 and 949 in 2014-2015 — who have experienced war or lived their lives in camps.

The newcomer center’s Casamayor-Ryan says it’s important to make second language speakers entering RISD feel welcome.

“That first impression here at the Newcomer Center is so important to letting them know we are helping them. We want them to have cognitive, social and emotional needs met while maintaining dignity, allowing them to feel included.”

The Newcomer Center staff tries to glean as much information as possible about students’ education and experiences so they can pass that information along to teachers and counselors at the campus they will attend, Casamayor-Ryan says.

They might be referred to the RISD clothing closet, where families who have lost their belongings can secure clothes and other necessities for their students.

The movement of people is and will continue increasing, and putting a face to it, meeting people, creates a refined sense of empathy and helps a student grow.

RISD spokesman Tim Clark says he cannot speak for the refugee resettlement organizations and how they place families, but the fact that Lake Highlands is lined with high-density apartment communities means there is more housing for refugee families. Thus, Lake Highlands schools accommodate a fair share of these students.

Specialists trained to teach second language learners move about the district, Casamayor-Ryan says.

Eva Wallace, who is in charge of translation services throughout RISD, says it has been a busy year, “especially as word gets out about our services.” The district placed signs at every campus and even at local hospitals to let parents know that interpretation services are available for school-related matters, she says.

“On the first day of school, four Arabic speaking mothers were trying to enroll their children but they were not sure how to proceed,” says Sarah Greenman, PTA president at Skyview Elementary.

Through earlier talks with District 10 City Councilman Adam McGough, she had met Richland College students who could translate Hindi, Arabic, Farsi, Urdu and Spanish. Greenman gave a number to the Skyview principal, who called one of the student translators at 7:30 that morning and, she says, one little girl’s face flashed a smile when she heard a person on the line speaking her language, Arabic.

The little girl was missing a leg, Greenman says.

“The children we sent into class are missing fingers and other parts of their hands. They, like hundreds of thousands of others, lived through the bombing of their home in Syria.”

Greenman is fundraising for an ancillary translation initiative for schools such as Skyview, where 10 to 12 languages are spoken on campus.

Wallace says the district is working with the business arm of Catholic Charities to keep the translators available, and RISD’s communication department is making an effort to get the word out.

With almost 40,000 students and 10,000 second language learners — 10 percent of those refugees — the Newcomer Center and its small staff entrusts the welfare of families and students to individual campuses.

Ashley Nick at a Burmese refugee camp.

Wallace Elementary, for example, hosts a large population of refugee students from Burma, sometimes by way of Thai refugee camps. Teachers such as Saw and Nick help make the transition easier for students and their families.

Looking back on the trip they took to visit Saw’s former refugee camp home, Nick says it helped her better understand specific needs of the students and families new to America.

“Since our return, we have been able to share our stories, observations, pictures, and video with the staff at Wallace, principals in RISD and at Region 10 training,” Nick says. “We have been able to create an awareness that will hopefully impact educators and students even outside of Wallace.”

And the benefit to American-born classmates of being exposed to other cultures and distant-seeming global situations cannot be ignored, Casamayor-Ryan says.

“The movement of people is and will continue increasing, and putting a face to it, meeting people, creates a refined sense of empathy and helps a student grow.”

Casamayor-Ryan’s daughter is friends with a girl whose parents are from Ghana and who speaks Italian.

“Here is this big family who has put extraordinary effort into one child’s education. She is in AVID [a college-track program in RISD high schools] and works hard, values her education — it’s the finest example of a child I’d want sitting next to my own at school.”