High school and our experiences there often leave lifelong memories. Or scars. Imagine navigating those formative and frequently frustrating years while bearing an extraordinary burden — illness, disability, poverty, homelessness, parental abandonment or death, for example. The graduating seniors featured herein have endured a lifetime’s worth of adversity in their 18 years. In spite of, or possibly partly because of these challenges, they have managed to shine.

Meet tomorrow’s leaders.

‘Richard! Richard! Richard!’

He was sitting in class when he heard the announcement. “Tennis team tryouts will be held this week …”

At the time, Richard Thawng was not overly concerned about having never held a racket. He had studied the game on TV. He envisioned himself, small frame darting across the court — lunging, swinging, smashing — his spiky jet-black hair restrained by one of those cool terrycloth headbands.

“And, I thought it might help me get into college one day,” he says.

He had endured so many hardships in his young life — fleeing his birthplace, years of poverty and oppression, and culture shock among them — that tennis seemed a cinch. He convinced a friend to join him. They did not have rackets, so they watched videos.

On tryout day, Coach Bob Williams stuck the boys on the farthest court to minimize “the risk of sprayed balls.”

Williams recalls them “banging, swatting, generally running around the court.”

But what grabbed Coach’s attention most was their “abundance of energy.”

It was summer, Williams recalls, “and as the veterans began to lumber in for water and shade, Richard and his partner doggedly continued hitting balls in the general direction of each other. They seemed to be swift on their feet, and they certainly had the drive.”

Richard laughs at the memory of the day. “I lied and told Coach I had played before because I wanted him to give me a chance. Everything I hit just flew, crazily.”

Williams remembers that the boys struggled with English.

“I peppered them with questions and learned they were Burmese refugees. Then Richard turned a question on me — ‘What must I do to have a spot on the team?’ My heart swelled …”

Williams knew what he had to do — Cutting the unskilled was part of the job. But he found himself giving them another week to practice.

“What was I thinking? I knew I was only postponing the inevitable. But I just couldn’t let the axe fall. There was something different about these two … They had earned the right to a little more time to prove themselves.”

So each day Richard and his friend walked to the courts by their apartment and played, with rackets on loan, until the lights went off at 10 or 11 p.m.

After dark, they analyzed YouTube clips of Roger Federer and Andre Agassi.

They returned the next week with “remarkably improved mechanics,” Williams says. Amazed, he and the assistant coach agreed — the boys had earned a spot on the team.

[quote align=”right” color=”000000”]“It was the best feeling we ever had,” says Richard of the day he and his mom finally gained entry to the United States, via a refugee program and a helpful uncle, a pastor at Dallas’ Chin Revival Church. They did not know any English, but Richard studied the dictionary furiously and became fluent within a year.[/quote]Four years later, Richard is ranked second on the Wildcat varsity tennis team and is team captain — the squad earned a place in the all-region tournament last year and is on track to do the same again. One night, after Richard won a particularly tough match, his teammates lifted him to their shoulders and carried him around the court while shouting, “Richard! Richard! Richard!”

When Richard was a child in Myanmar, then Burma, his father fled to America, assisted by a smuggler.

“He nearly died — several of his traveling companions did,” Richard says.

Richard and his mother moved in with an aunt in the city’s capital, but Richard says the woman took advantage of their inability to speak the country’s official language and pocketed the money Richard’s father sent for schooling.

So, during his formative adolescent years, Richard went three years without school. He used the time to self-learn the official Burmese language, and he and his mom moved away from his officious relative, Richard says.

“It was the best feeling we ever had,” says Richard of the day he and his mom finally gained entry to the United States, via a refugee program and a helpful uncle, a pastor at Dallas’ Chin Revival Church. They did not know any English, but Richard studied the dictionary furiously and became fluent within a year.

He still felt awkward speaking English and found it hard to make friends — noting his brilliant smile and infectious affability, it is difficult to imagine.

Today there is a large population of Burmese refugees in the Wallace Elementary School zone, but his family was among the first, so it was lonely.

Because Richard remembers what it felt like to feel completely lost, he is determined to help others in the same predicament.

“I will help people fill out job applications, insurance papers, go with them to their bank …” He says he thinks it especially important to help immigrants figure out finances, so they can become independent and not a victim to those who would take advantage.

Thus, his plan after graduation is to study finance at one of several universities to which he has already been accepted, including University of Texas at Arlington and Texas A&M Commerce.

His parents’ sacrifices drive him. “My dad risked his life. He came to America so I would have a chance at an education. In my country there is no way for a poor person to go to high school, college. My parents were unable to finish school, but it is all they want for me,” he says. “I have applied for every scholarship. I know I have been given this great opportunity and I will do everything I can to meet the challenge.”

‘I had to start my life all over.’

She has a mind for numbers. Especially dates. Dec. 23, 2005: Grandmother died; Nov. 18, 2011: Uncle died; Nov. 14, 2014: tore ACL; June 7, 2015 at 4:30 p.m.: Will graduate from high school.

Since early childhood, growing up on the harshest streets of southern Oak Cliff, meticulous organization — of drawers, closet, calendar — was how Leona Michael-Makelfa coped with chaos. At age 5, she developed a rare salivary gland cancer. Surgery saved her life, but left a scar on her neck. Due to a skin condition, the scar grew into a massive, protruding keloid. Her classmates teased her.

“Kids at school said I had worms in my neck,” she recalls.

Today Leona is beautiful with deep wide eyes, long eyelashes and an athletic physique. Aside from the discoloration on her neck — noticeable when she points it out — her skin is clear.

But self-consciousness and timidity about her looks has plagued her. She lived with her grandmother because her mom drove a taxi and worked long hours. “My grandmother was my rock. She was the one who helped me when going through the surgeries, when I felt hideous.”

Her father left when she was 2. “He has his own family, haven’t seen him in years,” she says.

But her grandmother died suddenly, shockingly at age 50. “It broke me and my family, and I had to start my life all over. She kept the family together. When she died, everything went wrong.”

Leona ate her pain and weighed 156 pounds by the time she was in fifth grade. She moved in with her mother, who had adopted the child of a former boyfriend and worked 12-hour shifts most days.

At Forest Meadow Junior High, Leona acted out. “Got in fights with boys, that kind of thing.” Leona’s mom lost her job and married a man who had twin sons.

[quote align=”right” color=”000000”]Drugs were always around, she says. It was part of life in her circles. She dabbled in such things herself, she says. “For a little while, it became my coping mechanism.”[/quote]“So it went from me, my mom and a little sister to having a stepfather and two brothers,” Leona says. “This made my struggle worse.”

Drugs were always around, she says. It was part of life in her circles. She dabbled in such things herself, she says. “For a little while, it became my coping mechanism.”

An uncle, one among a close-knit group of relatives, used heroin. He died in 2011 of an overdose.

Leona loves her family, but she wants a different life. Things started to change when she picked up basketball.

“I wasn’t the best player, but I loved it. I started to lose weight and become more confident.”

She endured radiation and regular steroid injections to treat the scar tissue — a grueling regimen, but it worked. During her freshman and sophomore years she flip-flopped between being the ostensibly ideal student — a member of AVID (a college preparation program) and starter on the basketball team — and slipping back into depression and self-medication.

She had always maintained good grades, but during the last two years her efforts sharpened. In the basketball team and AVID, she found a family. Razor focus on sports and academics kept her mind off the pain and anarchy that was her personal life. She tutored other kids in her spare time, and she worked as a teacher’s aide for AVID teacher Pamela Gayden.

“I love that girl,” Gayden says. “I didn’t want any student but her for the job. She is organized and hardworking, but more importantly, I can trust her … she understands integrity, honesty and character. She is invaluable to me, and she is a mentor and role model for all of my students.”

Leona was excelling on the court this year, preparing for a tournament in Orlando, Fla., when she suffered a serious knee injury, a torn anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) that knocked her out for the remainder of the season. It is a hard blow — after all, basketball and training had become a healthy way of coping with trouble — but she is taking the setback in stride. She still travels with the team and tries to be a positive influence from the bench. Schoolwork and her job at Fiesta grocery keep her busy. Her calendar is full, detailed and color-coded.

“I am a little what some people call obsessive compulsive,” she says.

Every element is planned — after high school, she will attend Lamar University where she will study American Sign Language. She does not know anyone who is deaf. She says a family friend who knew sign language sparked her interest. Specifically, she wants to be able to communicate with deaf teenagers in her possible future job as a juvenile probation officer.

“I’m interested in criminal justice, but I want to work with juveniles because I think they have a better chance of changing. Like I did. I think they need someone they can relate to.”

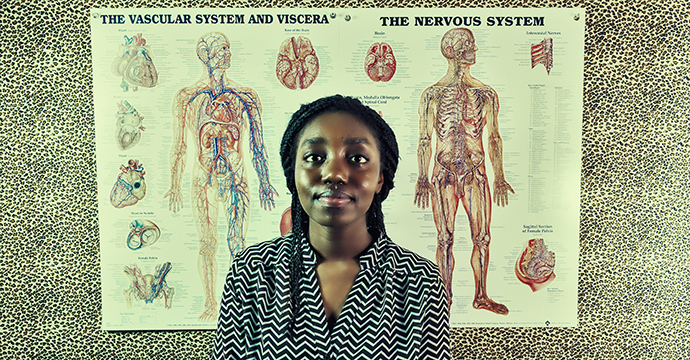

This American life

“Fancy.” That is how Diana Monyancha describes her first American home, a small apartment near Abrams and I-635. To Diana, electricity and running water equaled luxury.

“You flush the toilet and see it fill back up with water — that’s a sense of hope.”

She had seen a shower before, but never one that worked. And flowing hot water? It was a miracle. Her gratitude is immeasurable. She appreciates how close she came to not receiving an education, not having a teacher who would, for free, work with her after school on math, her toughest subject.

To this day, she eyes with wonder and skepticism freely offered bottles of spring water.

She is determined to take advantage of this unlikely opportunity — a life in America.

As a child, Diana lived in Kibera, a sprawling slum in Nairobi, Kenya where clean water, electricity, education and general safety — not to mention opportunity and hope — were scarce. “When it got dark, you needed to be inside,” Diana says. “If you had a job, you made sure no one knew your salary day.”

[quote align=”right” color=”000000”]As a child, Diana lived in Kibera, a sprawling slum in Nairobi, Kenya where clean water, electricity, education and general safety — not to mention opportunity and hope — were scarce. “When it got dark, you needed to be inside,” Diana says. “If you had a job, you made sure no one knew your salary day.”[/quote]Diana and her brother Timothy attended Kenyan school, but logistics were debilitating. “We had to use public transportation, and a lot of the time the bus drivers didn’t want to pick up kids, because we could not pay. Sometimes they would just pick us up on their last route, so we would get to school late.” The teachers often chastised them for their tardiness, Diana recalls.

After-school tutoring was for paying clients. Diana went to extraordinary lengths in her quest for a decent education, and she recalls promising teachers that her parents would pay for math tutoring, knowing they could not. “Then when I could not pay, it was so embarrassing, and I felt guilty.” Homework also was problematic. “We had to get it done before the sun went down, because we had no lights.”

Recounting the day she found out that her family had been selected for the United States government’s Diversity Immigrant Visa Program chokes her up. She looks at the ceiling and a tear trickles down her cheek. “I was so happy, so scared something would go wrong.” After 14 years of abject poverty, relentless fear and strife, she would have a new life. “We thought of America as a magical place,” Diana says. “At first I didn’t even believe it, and I told very few people.” She recalls sitting at the embassy, studying the other families, imagining their stories, praying nothing would go wrong for any of them.

Today, instead of waiting around for a bus, Diana drives a car she and her mother share. Over one shoulder she carries an oversized tote, laden with manuals and paperwork related to college scholarships. She hauls it everywhere, and people wonder: “ ‘Why are you carrying that thing around?’ they ask me all the time.” But in a way she is proud of her bag. She says she sees it as a sort of metaphor for the weight she’s carried all her life. Something good will spring from it, she knows.

America has not been perfect. In those early days, the friendless freshman spent numerous lunches hiding away in the library. But she used her time there to write, a lifelong passion and outlet. She also discovered the internet and social media, which, considering she had never owned a cell phone, blew her mind.

She scored a 38 on one of her freshman math exams. But pursuant to her mantra — “try, try again, try again” — she strived.

She did not learn the fundamentals of math when she was in Kenya, which made the transition to high school math exceedingly difficult. But Diana came in every day after school, formed study groups, and rose to the top of her advanced algebra class, math teacher Katie Williams says. “Diana is without a doubt the hardest working student I have ever had,” Williams says, adding that she is “clearly a respected leader among her peers.”

Diana joined groups such as AVID, which prepares students for college, and gained friends (“her disposition is one that attracts many,” Williams notes). She earned accolades and appointments — the Exchange Club’s Youth of the Month Award and Texas Leadership Forum among them.

Now a member of Mu Alpha Theta, an honors math society, she tutors struggling students “because I was once in their shoes,” she says.

To date, she has been accepted to University of Texas at Arlington, Texas Tech, Stephen F. Austin and Baylor universities. She’d prefer Baylor, she says, but cannot afford it. Applying for scholarships (and she thinks she’s found all of them) often requires attending interviews, which make her “a little bit nervous,” she says. “You tell your story and the memories hit you in the head, but the people are nice, and I know they want the scholarships to go to the right person. If I don’t get one, try, try again and try again.”

Adversity has given Diana an advantage over many young people — perspective. “The thing is, a bad day here is nothing compared to life there. So it is easy to stay optimistic.”

She anticipates setbacks and knows how to handle them.

“When life knocks you down, try to land on your back,” she says, quoting motivational speaker Les Brown. “Because if you can look up, you can get up.”