When it comes to investigating underwater, zero-visibility crime scenes, they are the best.

They are crucial when it comes to gathering evidence, solving cases and bringing closure to the families of drowning victims — for the police officers whose work takes them to the murky depths of Dallas lakes, a job well done usually involves a horrific discovery.

- Dallas Police Department dive team led by Jack Bragg. (Photo by Danny Fulgencio)

Dallas Police Officer John Boucher spent much of one blindingly sunny May afternoon submerged in White Rock Lake, searching for the “kid” who jumped from Mockingbird Bridge and never resurfaced.

Onlookers said they tried to find 24-year-old Jeremy Daughtry — who reportedly leapt in on a dare — but it was no use. Under the surface lay 8 feet of inky blackness, a glut of debris and limb-sucking sludge that vastly inhibits movement.

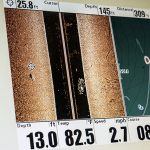

Even with the aid of side scan sonar equipment, Boucher, dive-team commander Jack Bragg and several more dive-team members searched some 16 hours before locating the body. By then, the young man’s parents were at the shore, holding one another; his mother sporadically sobbed.

Divers “bagged and tagged” the young man’s body at the bottom of the lake before bringing him to surface, explains Bragg. They positioned their small boat in a way that would shield the excavation from onlookers.

This is protocol.

“We have a job to do, but we are also thinking about protecting the loved ones, trying to be as respectful as possible,” Bragg says.

Once Bragg and his team are called to a scene such as this, prospects probably are grim. It means Dallas Fire and Rescue has exhausted recovery efforts.

The first dive, technically, is treated as a rescue, says Bragg, but they have never saved anyone.

“We are looking for bodies.”

Dallas police dive team members train in a Lewisville pool for real-world situations by wearing masks with blackened lenses: Photo by Danny Fulgencio

The Dallas Police Department Underwater Recovery team is made up of 22 police officers who also are specially trained divers. Team commander Jack Bragg, Captain Jack to most, works full time as the coordinator of the dive team, a DPD field-service unit that falls under the SWAT department.

The rest of the divers are posted elsewhere full time; two work as patrol officers at the Northwest, others at Northeast, South Central, and Southwest subdivisions, respectively. Others work narcotics or Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR).

When divers are needed — typically for the recovery of a drowning victim, a submerged vehicle or evidence vital to solving a crime — Bragg rounds up available team members. Calls can happen as often as three times in one day or as infrequently as three times in as many months.

Essentially, Underwater Recovery Team members investigate and gather evidence at underwater crime scenes. They wear thick rubber dry suits and about 50 pounds of gear and dive in 20 to 60 minute intervals, depending on conditions. They must be as meticulous and clean as an officer at any other crime scene, even though the environments in which they work are filthy and unforgiving.

“You want to know what it looks like under that water?” asks diver Daniel Hale. “Here you go.” He holds up a “blackout mask.” The lenses have been painted opaque black. “That’s what you see down there.”

Low-to-zero visibility, one of myriad challenges faced by underwater investigators, forces officers to feel for the targeted object.

Imagine a job in which getting your hands on a dead body or a body part means success.

“When you are down there, it is difficult to tell the difference between a foam seat cushion and a human body,” notes Northwest patrol officer/Senior Dive Officer Scott Harn. And there are a lot of foam seat cushions in White Rock Lake, remarks another officer attending a recent certification class.

For our benefit, Bragg asks the group, which also includes Lewisville divers, how many dead bodies they had touched. “I lost track,” one says. “Too many to count,” another notes.

Logistically, training for public safety diving is formulaic and precise.

It is a Wednesday morning in August when dive-team members gather at a Lewisville Fire Department scuba pool for class. Lewisville is home to one of the country’s more sophisticated dive teams, due to the proximity of Lake Lewisville, Bragg explains. Dive officers are learning to use new equipment including surface-supply air tanks, which, compared with scuba tanks, will allow longer dives, and a communication box that allows divers to speak with and hear an operator on land. Until now, communication between diver and his colleagues on the boat and shore has been conducted via a coded system of rope pulls — one pull means, “all is well” while three means, “we found the body,” for example.

Before applying to Dallas’ dive team, an officer must be, at minimum, an International Association of Nitrox and Technical Divers (IANTD)-certified rescue diver. Police divers-in-training then follow a strict curriculum of schooling and certification that is in line with national standards.

Every dive-team member learns every position.

“Everyone knows every step of every operation,” Bragg says, “and it has to happen the exact same way as it will in the field.”

The team formed less than 10 years ago and operates on a limited budget. “We are not a dedicated unit so we get about $5,000-$7,000 of the SWAT budget and beg for grants and money,” Bragg says. Over the years, usually through grants or donations, they have acquired advanced equipment, but they cannot dive with new gear until they are properly trained and certified to use it. So they continually are brushing up on their skills and learning new practices.

“The dark side of why we have to do all this training is that [police departments nationwide] have killed so many divers,” Bragg says. “The last thing I want to do as a dive team commander is send a live person after an inanimate or lifeless object and lose him. Guys have been hurt. One of our dive captains had a lung embolism that ended his diving career. We do everything we can [to narrow every chance of injury], even though sometimes you can do everything right and still have something go wrong.”

Bragg lifts his pant leg to reveal a severe burn-like scar, the result of a cut that became infected in contaminated water.

Team members pride themselves on operating pragmatically even in the most outrageous situations.

In summer 2010 the dive team launched a hunt in a Preston Hollow pond for evidence linked to a 1983 murder.

“In that little pond, we found six or eight motorcycles and motorcycle parts, a safe, and several weapons including assault rifles and a handgun,” Bragg recalls. “None, by the way, were what we were looking for.”

The job demands painstaking levels of patience. It requires a deeply rooted understanding of procedure and the critical thinking skills necessary to apply it to an infinite variety of high-stake situations, Bragg says.

“We are very methodical. We are grandmas when it comes to collecting evidence — slow and meticulous. We aren’t going to be the reason some guy gets off because evidence was mishandled.”

The psychological demands of police diving, one could argue, are as grueling as the physical requirements.

Senior diver John Boucher is smoking a cigar. He says he finally quit smoking cigarettes, but he still likes the occasional cigar, and sometimes a drink or two, to help quiet his mind, especially after a tough underwater search.

“The worst, for me, was the first body I personally found. It was a few years ago at Lake Ray Hubbard. Party Cove. The guy jumped off a boat and never came up. I was the second diver and I found the body. When I touched it, at first I thought it felt like a roll of carpet. Then I realized it was the kid. There was an initial rush of anxiety but then the training kicks in and you go right into action.”

Sometimes, due to the darkness, divers experience what they call “mind monsters” — that is, the anxiety and dread that threatens rational thinking, Boucher says. Only a large dose of mental toughness can slay these beasts.

Usually, because of their high levels of skill, experience and training, divers like Boucher are able to launch into action even in the face of horrific circumstance — this Dallas dive team has located a murdered baby, drowned children and a bucket containing a human head, to name a few particularly disturbing cases, and all of these operations were handled perspicaciously and by-the-book, Bragg says.

Sitting at home, alone with his thoughts after long hours in dark waters looking for a body or a murder weapon, however, Boucher sometimes feels haunted.

“I’ll tell you, it messed with my head,” he says recalling the drowned man at Lake Ray Hubbard.

Like war buddies, divers often turn to one another for support.

“There are always two divers that bring up a body,” Boucher says. “That night we texted each other back and forth.” It doesn’t take much, he says, because each understands what the other is feeling.

Captain Jack’s worst day has to be the day, last May, when the dive team got the call about former assistant police chief Greg Holliday.

“Greg was a friend,” Bragg says. “I worked with him for 35 years. That’s about as close as you can get to having to look for your own family.”

Holliday, 63, had been missing for days. Police, in a Critical Missing Person alert stated that Holliday was possibly suicidal.

Bragg’s men, along with Texas Parks and Wildlife Department divers, found Holliday’s body, with a self-inflicted gunshot to his head, in a shallow creek near the Preston Trails Golf Club.

“Of course every guy out here has a different worst day, but I’ve gone through some of our police photos from that day, and you can see the stress on our guys’ faces. That day was hard.”

“The police department has psych [-ological counseling services], but this work is not typical,” Bragg says. “Regular patrol officers, they don’t really understand exactly what our guys go through.”

Several members of the team concur that the bonds they share among themselves are therapeutic.

“We are all friends. They have to be comfortable with and trust the other guys they are down there with,” Bragg says.

“Body recovery is stressful,” Boucher says, “and you get home and try to talk to your girlfriend about it, she doesn’t want to hear it. So you text the guy who was [on the job] with you. That’s sometimes how you get through the night.”

Private donations Captain Jack Bragg says he works hard to secure grants and donations and that the team frequently borrows necessary equipment from Dallas Fire-Rescue or from other nearby departments such as Lewisville. The side-scan sonar equipment used to recover Jeremy Daughtry, for example, was borrowed from Dallas Fire-Rescue, Bragg notes. He says private donations — which go directly toward purchasing equipment and training that makes public-safety diving more effective and less dangerous — always are welcome. For more information, email jack.bragg@dpd.ci.dallas.tx.us.

- Divers in 2014 prepare to enter the water in a training exercise. Photo by Danny Fulgencio