Leorah Mims came up with the idea after attending one too many faculty meetings cluttered with empty chairs.

To give teachers something to look forward to at the meetings, she implemented a drawing for gift certificates to area restaurants and movie theaters. The feedback was positive, and Mims – assistant principal at Lake Highlands High School – saw the idea as a way to generate positive results in student behavior as well.

Mims spent the summer tirelessly approaching local businesses to contribute goods and services as prizes. And after many calls to Big Billy Barrett, she finally secured the grand prize – a new Jeep.

Gena Bailey, owner of the Dallas Big Billy Barrett dealership and daughter of Big Billy, admits she was somewhat reluctant when first approached by Mims.

“When someone calls and asks that you give them a new car, your first reaction is to be wary,” Bailey says. “but then I began listening to what Leorah had to say, and I started getting that warm, fuzzy feeling.”

Bailey says her sons – one a recent Lake Highlands graduate and the other a sophomore – encouraged her to be part of the program. And the donation has generated business for the dealership.

“We’ve had people come in from Lake Highlands to buy new cars, and they mention the Jeep. To me, that is the mark of a good strong community – a kind of trading of services among the people who live there.”

In the end, though, she credits Mims’ persistence.

“I decided to go for it because she kept twisting my arm, and it hurt!”

The evolution of incentives

For years, incentive programs have been utilized in the workplace to boost morale, reinforce positive behavior, and proactively address problems. Today, we’re seeing this motivational tactic spilling over into our educational system.

Some parents pay their children for good grades. Gone are the days when you got yourself to school, on time, and behaved appropriately because to do otherwise would have meant punishment. Such negative reinforcement is now seen as arcane, if not inhumane.

How valid is this new approach to discipline in our schools? So far, the results seem to support the theory.

Throughout the Richardson Independent School District, incentive programs are used extensively to elicit, or suppress, a variety of behaviors from students at both the elementary and secondary levels.

Are these programs truly causing children to behave differently and, if so, for what reasons?

Good citizens

Moss Haven Elementary is committed to inspiring students to act as good citizens at school. The school’s incentive plan emphasizes developing positive social interactions by practicing acts of responsibility, courtesy and, most importantly, kindness. Teachers and staff pass out “Good Citizen” slips to students who are observed displaying this type of good behavior.

“We really focus on rewarding acts of kindness and unselfishness, because ‘good behavior’ means so many different things at each individual grade level,” says Principal Carole Kilduff.

“For a kindergartner, simply being still in line can qualify as outstanding behavior.”

Each Friday, one “Good Citizen” is drawn for each grade level. Winners receive a token for a treat at lunch, as well as have their name published in the weekly “Principal’s Report.” Kilduff believes the program positively impacts students.

“This is a program we implemented a couple of years ago,” she says. “We dropped it for awhile, but have recently gone back to it because of the positive feedback from the children.

“When I announce the winning names, all the children cheer for the winner from their group. It builds team spirit.” Other schools utilize incentive programs not merely to encourage positive behavior, but to address specific problems.

At RISD Academy, for example, students last year often didn’t comply with the dress code.

“We are trying a new motivational twist for getting students to wear their uniform,” says Principal Rita Latimer.

“Classes with the highest percentage of students wearing uniforms participate in a drawing for a special field trip to Barnes & Noble to buy books. The winning class receives $200 to buy books for their classroom libraries.”

Latimer sees a benefit to this positive approach to discipline.

“We are hoping that this special way of rewarding classes will help us increase school spirit,” she says. “Last year, dress code violations were dealt with in a rather negative way. We are trying to approach the problem from a totally different angle.”

Lake Highlands Junior High has enjoyed overwhelming success with its program, which combines mandatory detentions and voluntary tutoring opportunities.

The “Saturday Enrichment Program” was developed last year by Principal Bob Duvall. Every other Saturday from 9-11 a.m., faculty members and parent volunteers are available to help students with specific subjects and TAAS skills. Some students are assigned to Saturday Enrichment as punishment, but many come voluntarily to take advantage of the extra help provided.

“I would estimate that at least half, if not three-quarters of the students who come on any given Saturday are there on a voluntary basis,” Duvall says.

He developed the program as a way to address two specific problems.

“For one thing, it keeps kids who have acquired many detentions from being removed from the classroom and placed in In-School-Suspension. They are able to work off the time on Saturday mornings.”

In addition, Lake Highlands Junior High recently was named a priority school.

“We have some specific factors here, such as a high mobility rate, which cause our students to be more at-risk. Also, our TAAS scores needed some extra attention.”

Duvall believes that bringing everyone together on a Saturday morning makes more sense than traditional after-school programs.

“At the end of the day, everybody is tired. On Saturdays, the atmosphere is more relaxed – the teachers and I are in blue jeans, which is not how they usually see us. It seems like there is a little more bonding on Monday morning for the teachers and students who have come to Saturday Enrichment.”

As a reward for hard work, Duvall opens up the basketball gym for free play from 11 a.m. to noon. The program has seen great results so far – an average of 70 students show up on any given Saturday morning.

From treats to wheels

Of course, pizza parties, treats and gym time are a far cry from winning a new car. But then, what could possibly mean more to a teenager?

And according to the students and faculty at Lake Highlands High School, a chance to win a Jeep has measurably changed attitudes and behaviors at the school.

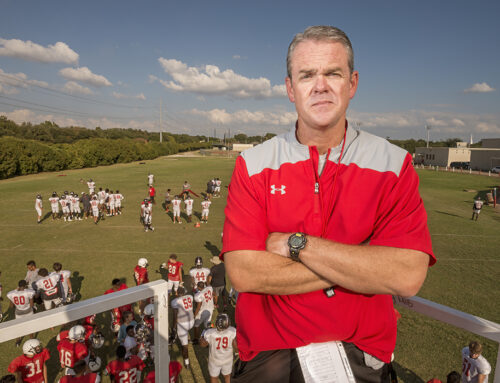

Once she had the Jeep prize donated, Mims was ready to implement the program. To be successful, Mims wanted to ensure that all criteria required to win are in the students’ full control.

“The criteria are that the student can have no tardies, no unexcused absences, and no suspensions for a six-week period,” she says.

That way, she says, students don’t need to have perfect attendance to qualify.

“A student can’t control factors such as getting sick or a family trip, and I didn’t want those students penalized for those types of excused absences.”

At the end of each six weeks, the names of qualified students are entered into a drawing for prizes such as dinners, gift certificates and cash. Each six weeks offers a new chance to qualify, and all students who qualify during various six-week periods throughout the year are entered in the year-end grand prize drawing.

Mims believes it’s important to give students a new chance to qualify every six weeks, and the students agree.

“I think it’s good that every six weeks you get a new chance. Otherwise, a student may get one tardy and just give up because they wouldn’t have a chance to win,” says Lisa Flach, a senior who has both qualified and won a prize.

Paying attention to the bell

Junior Carolyn Westfall describes herself as someone who fell victim to the “occasional tardy.” She says the incentive plan has changed the way she schedules her time at breaks.

“Before, I would try to get something extra in before the bell rang,” she says, “but now I look at the clock and think: Uh-oh, I’d better get going to class, or I’ll be late!”

Westfall says her attitude is the prevailing one among her classmates.

“You overhear people in halls saying things like: I’ve gotta run, I can’t be late.”

Such respect for the tardy bell hasn’t always been the case, and junior Kelly Kepley believes the incentive plan has visibly changed things at the school.

“There are not near as many people loitering in halls,” she says, “and there are hardly ever any hall sweeps.”

A “hall sweep” was used last year to clear the halls of lingering students: Anyone caught in the hall after the bell rang was given “Saturday School” – a Saturday morning detention/study hall.

Although Kepley didn’t experience a problem with tardies, she prefers the new system.

“Positive reinforcement works better,” she says. “Both teachers and students are excited about the new plan.”

What is the problem?

Is there a down side to reward tactics at school?

“You bet,” says Dallas based family psychologist Honey Sheff.

She’s firmly opposed to practices such as parents paying for grades.

“The philosophy is that you do not want to extrinsically reward someone for a behavior you want them to intrinsically develop.”

While it is perfectly acceptable to reward good behavior, Sheff says, the goal should be to help children find internal motivation for such good behavior. Certain types of incentive programs can work contrary to this goal.

“There is a concern that if you always give a child an external motivation to do something, you can kill their ability to internally motivate themselves. They lose the desire to simply do something good for themselves.”

Are the students at Lake Highlands grappling with that fine line between external reward and internal incentive? While it’s hard to predict the long-term effects of this new approach to discipline, the short-term effects are clearer.

Senior Shanelle Guillory says she’s trying hard to mend her ways in order to qualify for the Jeep, and although she hasn’t qualified yet, she remains optimistic that she will qualify in future six-week periods.

“I’m going to try my best and hardest to make it next time,” she says.