Buffalo Bills safety Damar Hamlin, 24, collapsed following a tackle in Monday’s game versus the Cincinnati Bengals, and he did not get up.

He suffered cardiac arrest and his heartbeat was eventually restored on the field, the Bills reported in a Twitter statement.

Damar Hamlin suffered a cardiac arrest following a hit in our game versus the Bengals. His heartbeat was restored on the field and he was transferred to the UC Medical Center for further testing and treatment. He is currently sedated and listed in critical condition.

— Buffalo Bills (@BuffaloBills) January 3, 2023

For some athletes and coaches in Lake Highlands, the event will likely bring reminders of a similar terrifying event that happened at the Lake Highlands Junior High Track six years ago.

In January 2017, we published a story about then 13-year-old Joe Krejci who collapsed during a track workout. Fortunately his coach Craig Titsworth responded swiftly, sending the two fastest track runners to the school nurse. Runners Blessed Divounguy and Max Orvik and nurse Annie Young returned to the track with a portable A.E.D. device, an automated external defibrillator designed to shock an arresting heart back into rhythm.

In 2007, Texas passed a law requiring an A.E.D. in every Texas school. That’s because what happened to Hamlin on the football field is a common occurrence in gyms, pools, tracks and other places where athletes train. In fact, we learned when reporting that story that sudden cardiac arrest is by far the leading cause of death in student athletes.

About one or two in every 100,000 athletes experience sudden cardiac arrest each year, according to the Sports Institute. Males are at a greater risk than females and Black athletes are at a greater risk than white athletes. The risk is higher in football and basketball.

At every Richardson ISD campus, teams of five-to-10 staffers, usually front office personnel and coaches, are specifically trained for critical situations, explained Richardson ISD special assignments nurse Alicia Whitehead, who had been coordinating CPR and first aid training for district employees for 11 years.

“We take it very seriously,” she said of the emergency response program, “because we want our students to be safe.”

The district allocates money not only to place and maintain the requisite A.E.D.s in every school (five high schools, eight middle schools and 41 elementary schools) but also to add multiple devices in the bigger campuses and even more at the high schools.

In district sports, team managers carry portable A.E.D.s. Choir and band directors carry them when the groups travel.

“We are required by law to check each once a month, but we check them daily,” Whitehead said.

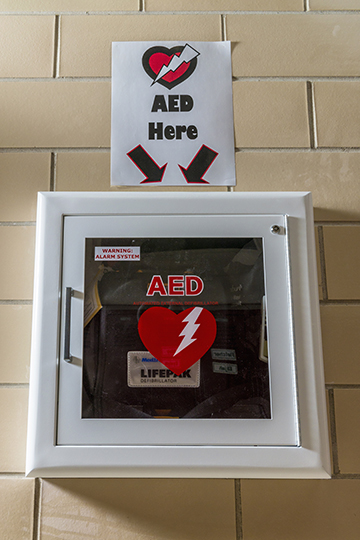

The devices are stored in recessed, reachable cabinets, usually in school hallways, outside a nurse station or the gym. Bright, visible signs, posted around campuses, advertise A.E.D. locations.

Though several employees at each school are trained to use an A.E.D., the machine is user friendly even for a layperson in an emergency.

“It talks to you. It tells you what to do,” Whitehead says. “We want them to be accessible, even if it’s at an event after hours and the nurse is not around.”

Fort Worth mom Laura Friend lobbied for Texas’ A.E.D. law after losing her swimmer daughter to cardiac arrest in 2004, and she created a nonprofit that has donated A.E.D.s and provided training throughout Texas.

In 2017 RISD spokesperson Tim Clark told us A.E.D.s have been used as an emergency response on at least five occasions that he can recall in the district. And most importantly, “we have never lost anyone as a result of cardiac arrest, at least in the 15 years I have been around,” he added.

Blessed Divounguy, Craig Titsworth, Annie Young and Max Orvik surround Joe Krejci, whose life they teamed up to save. (Photo by Danny Fulgencio)

At that Lake Highlands track in December 2016, the track coach, by profession a stickler for time, noted that Joe dropped to the ground at 3:04 p.m. He delivered the shock at 3:12 p.m. The ambulance arrived at 3:15 p.m.

At the hospital that night doctors told Joe and his parents that the shock saved him — that he could have died if they’d waited even a couple more minutes.

In fact, a victim’s chance of surviving this type of cardiac arrest “drops by 10 percent for every minute a normal heartbeat is not restored,” according to the American Heart Association.

Doctors outfitted Joe with a pacemaker, the teen was back at school before Christmas break.

The condition of the 24-year-old Hamlin is has not been updated as of midday Tuesday, but we can hope the first medical responders reacted in time.