Photography courtesy of DALLAS CITY HALL | Map courtesy of DALLAS MORNING NEWS

Northlake Shopping Center and homes to the west, east and north of the strip center sit along the streets of Shoreview and Ferndale; that’s where the core of Little Egypt existed for nearly 100 years.

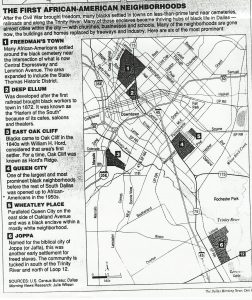

Little Egypt was one of Dallas’ eight freedmen’s towns, neighborhoods where newly freed slaves lived after the Civil War.

“Just a couple of years after Little Egypt was gone, I actually lived in Lake Highlands,” says Clive Siegle, a Richland College professor leading the ongoing excavation of an empty lot that was Little Egypt.

“My parents bought a house about half-a-mile from the house that I’m in now.”

A freedmen’s town is a historically Black community, typically located in the South and “founded via cash purchase or adverse possession, often in flood-prone bottomlands on the edges of plantations and city boundaries,” according to the Texas State Historical Association.

Following the Civil War and Reconstruction, formerly enslaved African-Americans sought places to live and raise their families. Few of these communities survived Dallas’ transformation into a bustling metropolis, except for some churches and cemeteries.

“When it comes to freedmen’s towns, usually you’ll find a cemetery, especially a Black one, and you’ll find an older congregational Black church,” says Dr. George Keaton, a genealogist and historian.

Photo courtesy Little Egypt Church

“Even though they may not be there, like Little Egypt, the congregation that’s there still exists when they moved in the mid-‘60s. And then you’re going to have some evidence of some type of business because [residents] had to be self-sufficient.”

Little Egypt was a pocket that was once a small, yet significant, part of Lake Highlands. The name of the community alludes to the slaves finding freedom from Egypt in Bible stories.

The 35-acre land was deeded by former slave owners to freed slaves Jeff and Hanna Hill in 1865 for $300. One of the original buildings was the Little Egypt Baptist Church. The community grew to about 200 as residents built their own houses.

The Hill family pioneered the community, but the McCoy family also was influential. Theirs was the only house in Little Egypt with a telephone line. The community was centered around the church and had no running water nor electricity, Siegle says. Though lack of city services was often a characteristic of Texas rural communities at the time, it was especially common in freedmen’s towns because they generally were established away from city centers and more valuable developments.

“Take a look at the landscape in 1930: It’s pretty deserted land, but you’re looking at the same land that pioneers were looking at in the 1850s,” Siegle says.

“There was no plumbing anywhere in that development. (Residents were) still using outhouses,” Siegle says. “If you are familiar with the sticks in rural Texas, you’ve got these water tanks up on stilts kind of behind the house. That’s what they’ve got here. It was still rural, in its own way.”

On a single day — May 15, 1962 — all of the Little Egypt residents moved out of the neighborhood, and the entire community was bulldozed. A year earlier, the residents had agreed to sell their homes and community to a developer for a few thousands of dollars apiece, and they looked forward to life in a neighborhood with utilities.

“It was commercial real estate development that took over the neighborhood,” says Collin Yarbrough, a Lake Highlands resident and author of Paved A Way. “It was a little more peaceful than some of the others.”

The Little Egypt exodus made national headlines. An archived clip from New York’s Oneonta Star newspaper says William Hill, 87 at the time, was concerned about something other than his future: “The community’s patriarch, William Hill … worried about his long unused sets of mule harness.”

The Little Egypt Church relocated to Oak Cliff in 1962, because that’s where the church congregation and many of the former residents moved, taking a piece of their former home with them.

The McCoy house was built on the now-empty lot behind East Lake Veterinary Hospital, Yarbrough says.

Photography courtesy Richland College Media

“That’s where their family home was, and it’s the only hub that was never built on top of,” Yarbrough says. “So, it’s kind of the only last vestige of Little Egypt facilities.”

Surviving McCoy family members in the Dallas area helped Richland students working on the excavation find more “Egyptians” and descendants to interview. Jerry McCoy and his siblings gave students contact information for other residents who grew up in Little Egypt. The McCoys also drew a map of the area and provided more family names.

Richland students excavated the McCoy lot from 2015-2019, but the project slowed significantly as a result of the pandemic. The technological part, including building a virtual reconstruction of the McCoy house, is still in progress.

There’s now a historic marker for the site that has yet to be put up due to health and safety protocols created by the pandemic, Siegle says.

“There’s a ceremony that goes with it. It’s a state historical marker; it’s a big deal,” he says.

In the future, Siegle also hopes a museum can be established to showcase excavation finds, articles and other items related to Little Egypt and McCree Cemetery, where many residents are buried.

“What we’re trying to do is keep going … and eventually have it to the point where we reach a critical enough mass that we could actually have a museum exhibit.”

For more information about Little Egypt and other freedmen’s towns in Dallas, visit Freedmen Towns of Dallas County: An insight Presentation and Discussion on Facebook.