The police officers, secretaries and chairman work two 20-minute shifts per day. So does the sheriff, banker and translator. They save their paychecks to exchange them for $5 gift cards.

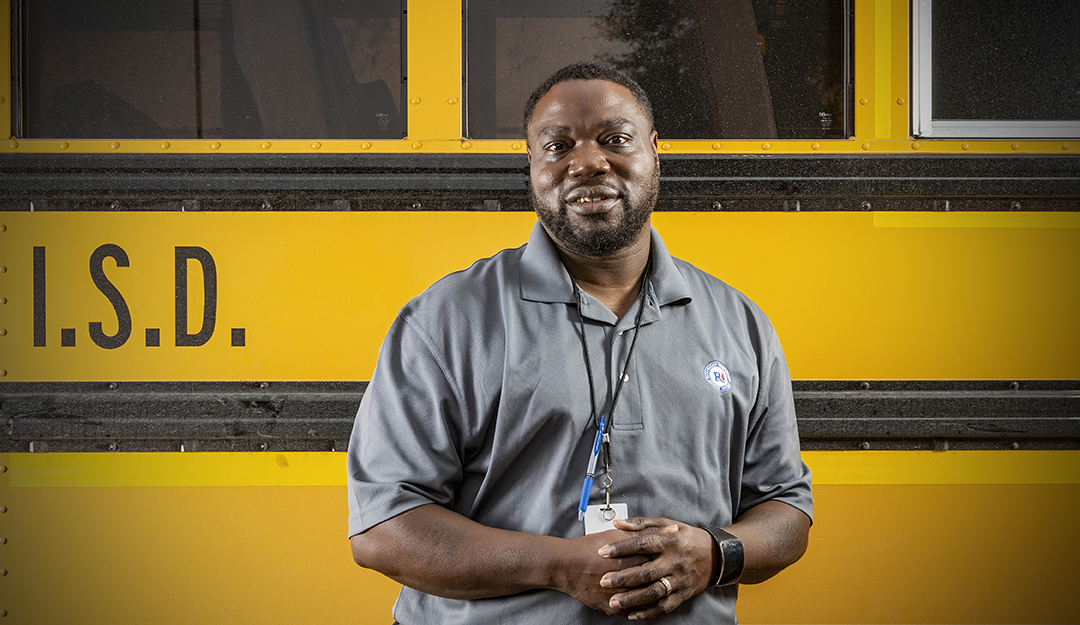

Their boss, Curtis Jenkins, is nothing if not reliable. He picks them up in the morning and takes them home every afternoon. He never asks them to work overtime.

They are, after all, elementary school students.

The 46-year-old Lake Highlands Elementary bus driver has created a community inside bus No. 1693. Students apply for their jobs and earn “bus bucks” that Jenkins designed himself. Children who don’t work receive a weekly stipend, but they’re taxed $2.

Students are fined when they break Jenkins’ rules, which are centered around respect and compassion.

“I’m teaching love,” he says. “If you don’t love, it might cost you some things.”

It’s no classroom, but Jenkins plans daily lessons that he worries are otherwise neglected. Girls get on the bus first in bad weather, he says, because they’re “queens of the future.” He shows students how to fly paper airplanes and tie a tie.

“I want to put imagination back in children without desensitizing them,” he says.

Students campaigned for president in March and were tasked with creating a budget to add more jobs. But multiplication is tricky. So is public speaking, which is why one fifth-grader dropped out of the race.

“Look, all you need to say is some fancy words, and something that’s going to make everyone excited or something,” one second-grader advised him. “Then they’re going to choose you. It’s not that hard.”

Jenkins has held an assortment of jobs, from owning a plumbing and electric company to truck driving. Then, eight years ago, his mother became sick. He needed a flexible job to take her to appointments.

“Everybody always asks me why I drive a school bus,” he says. “I tell them I’m on a mission from God.”

Since December, he’s collected hundreds of thank-you cards and articles. One January afternoon, he sets a stack of stories on a table at Panda Express. In a rare turn of events, The Huffington Post, People, The Christian Post and even far-right nationalist outlet Breitbart share similar headlines. A generous Dallas bus driver bought Christmas gifts for all his students.

Jenkins pulls his phone out of his pocket and pulls up another story featuring his photo. He doesn’t recognize any of the words — or the alphabet.

“I don’t even know what language this is,” he says.

Jenkins has been inundated with phone calls from nonprofits, TV stations and talk show managers since he and his wife bought dozens of presents, meticulously wrapped them and gave them to students for the holidays.

The act was not out of the ordinary for Jenkins, who makes each student a birthday card and buys turkeys for families in need on Thanksgiving.

Lake Highlands Elementary thanked Jenkins on Facebook that Friday, clueless that the post would be shared 13,500 times and his story would run across media outlets in 20 countries.

By the time Jenkins and his family were at church Sunday, the act of kindness went viral. Jenkins transformed into an internet sensation within 48 hours.

“Everybody capitalized on what I did,” he says.

Jenkins wasn’t prepared for the nonprofits who claimed they donated to him, even though he’s yet to receive any money. A company is turning a profit by sending thank you cards to him on behalf of their customers. His daughter wasn’t ready for the 2,000 Instagram followers who flooded her inbox in search of her dad’s contact information. Jenkins didn’t expect to buy a P.O. box or hire a lawyer to establish a nonprofit.

Jenkins didn’t return phone calls immediately. He fasted—only eating once per day — and he thought.

“Some people call it praying. Some people call it meditating,” he says.

If I have a platform now, why not use it, he decided.

Jenkins’ nonprofit, Magnifying Caring and Change, is an extension of what he does for the students on his bus. He’s looking for other people to help him, although he’s skeptical of their intentions. He partnered with Cozy Coats for Kids to buy jackets for students. Ideally, one day, he’ll have a community center for them after school.

Jenkins grew up in Crowville and Winnsboro, Louisiana, which was still segregated in the mid-1980s. He wasn’t allowed inside his childhood best friend’s house because his father was a member of the Ku Klux Klan. He couldn’t play on certain baseball fields, and he was taught which streets to avoid walking at night.

These memories aren’t something he mentions to the students, but it’s why most of his lessons revolve around acceptance. Jenkins’ goal is to be the mentor he never had, he says.

“If I had a mentor when I was young, I would’ve run for president at age 21,” he says.