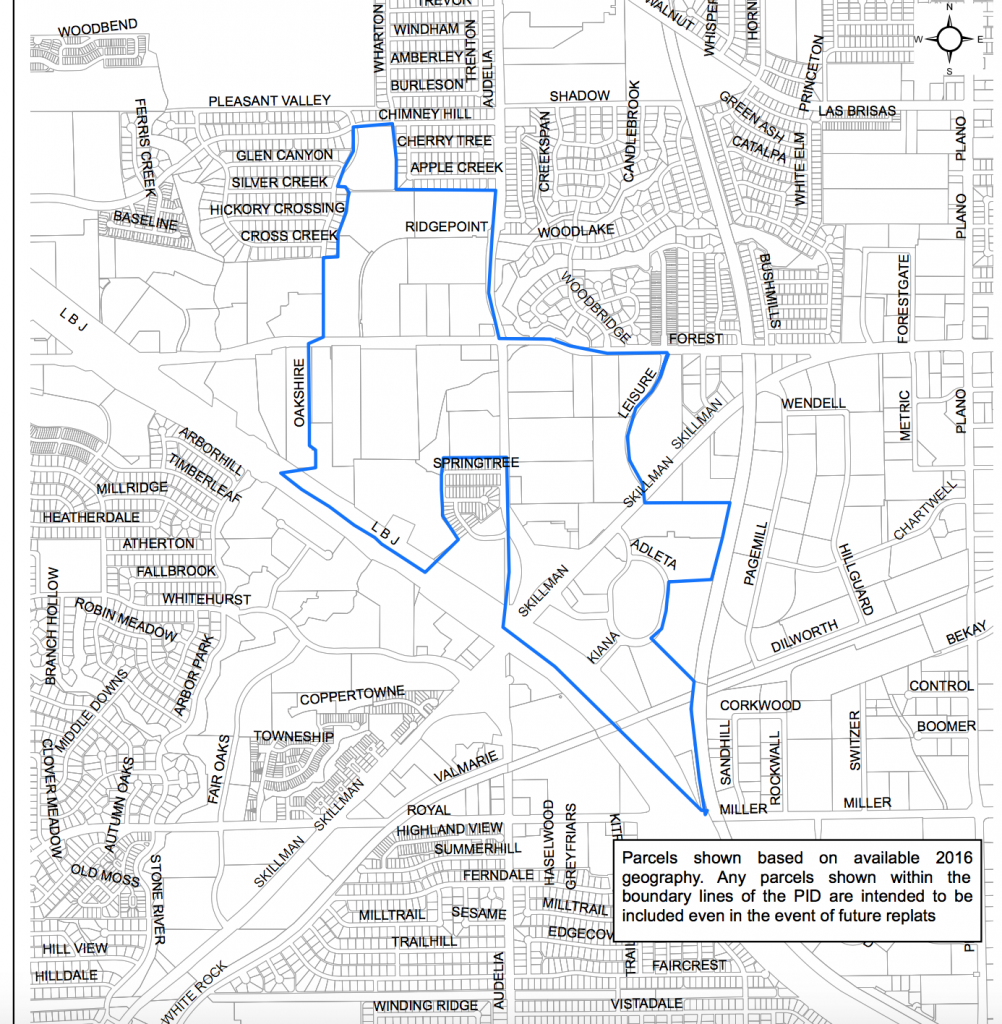

The boundaries of the newly formed North Lake Highlands Public Improvement District.

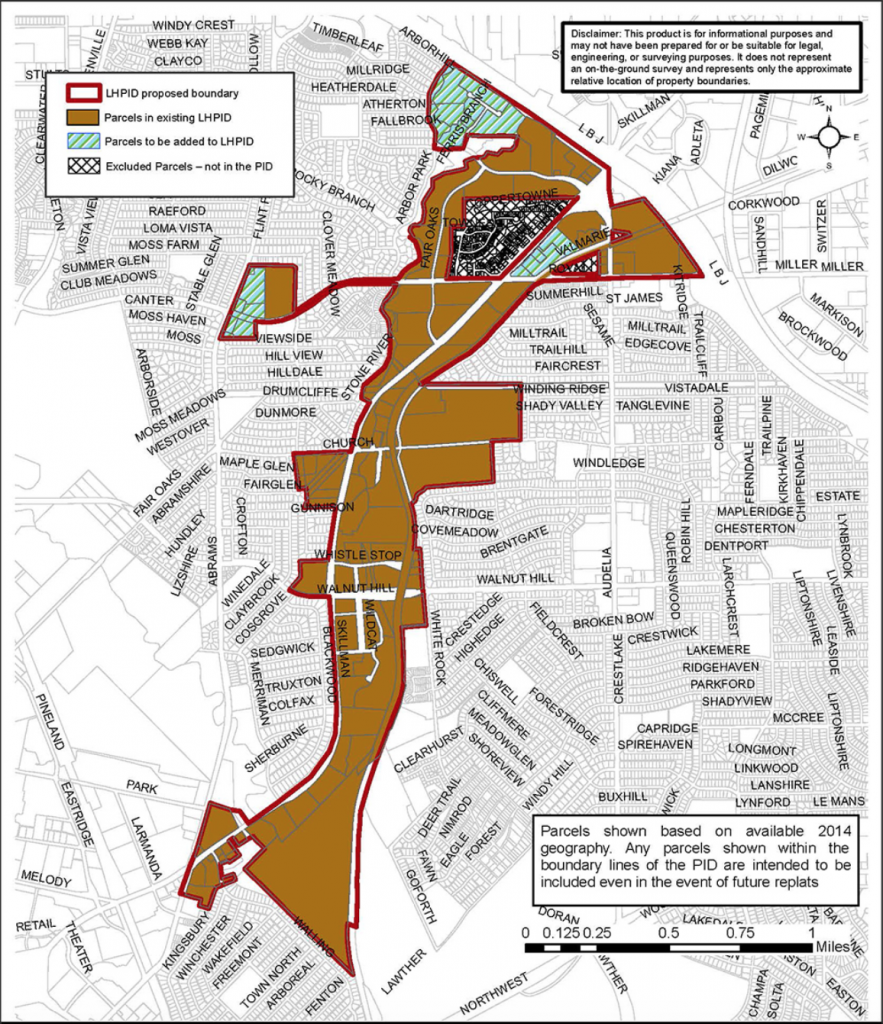

In 2006, the area now covered by the Lake Highlands Public Improvement District (PID) saw 1,358 crimes, including burglaries, rapes and car theft. That was before the PID began operations in 2009. As of 2015, the most recent stats available for the area, that number dropped to 571.

“There are a number of factors that contributed to the drop in crime – like the old apartments at Walnut Hill and Skillman being torn down in 2007, as well as the work of DPD,” says Kathy Stewart, executive director of the LHPID. “But, we know our work has been a factor as well.”

Stewart and her team are now planning to take that work north of LBJ with the newly launched North Lake Highlands PID, which goes into effect on Dec. 1.

It’s been months in the making, however, since a PID can only be proposed with buy-in from property owners who represent 60 percent of the area’s total land valuation. Stewart has been busy targeting big property owners to explain the benefit of paying an extra tax to support everything from crime reduction to beautification to special events.

“We’re focused on improving quality of life in the neighborhood,” Stewart says.

In a PID, the city’s office of economic development sets the tax rate based on property values. In the new North Lake Highlands PID, property owners will pay 12-cents for every $100 of valuation, resulting in an annual budget of $360,000 for 2018. By comparison, the recently renewed Lake Highlands PID charges property owners 13-cents (per $100 assessed value) for a $600,000 budget in 2018.

Flanking either side of LBJ, Stewart said each PID will exist on its own but the two will also find ways to benefit each other. Both will exist under the umbrella of the nonprofit Lake Highlands Improvement District Corporation, but each PID will have its own advisory board focused on the issues specific to that neighborhood.

“Every PID is totally different, we have to adapt to what’s around us,” says Vicky Taylor, public safety coordinator for both PIDs.

Boundaries of the Lake Highlands PID, which went into effect in 2009 and was renewed for another seven years in 2015.

Stewart and Taylor, along with their business partners, agree that crime reduction is a critical goal of the NLHPID, which will dedicate 60 percent of resources to safety initiatives in its first year. They will work with Dallas Police and city prosecutors on strategies to target high-crime areas, but add that building community is equally as important for crime reduction. In the LHPID, that began with giving kids something to do.

“You have all these kids just hanging out during the summer, wreaking havoc,” says Taylor. So they created a massive teen job fair to help kids find work over the summer, which drew nearly 2,000 youths this year. They also helped support a new boxing gym to provide another healthy outlet.

On the northern end of the neighborhood, the need for youth activities is even greater, Stewart explains. “There’s not a library north of LBJ. There’s not a rec center. There’s not a park,” she says. “When we saw that lack of city resources and the crime, we knew we could do something.”

Taylor has also seen success in the LHPID by working with the apartment complex managers and owners, bringing them together to find common ground. Where before a problematic tenant could be evicted from one apartment only to get new one across the street, now the complexes notify each other to keep such people out of the neighborhood. Quarterly meetings with the 24 complexes in the PID and weekly crime reports keep the conversation going.

“It’s mostly about getting people talking and identifying common problems,” Taylor says.

Beyond crime reduction, PID’s provide neighborhood beautification, most commonly in landscaping. While they can’t always afford to do the initial installation, like the one coming to Wildcat Way by the Lake Highlands Town Center, they can provide ongoing maintenance to keep the area flourishing.

“The city doesn’t have the budget to maintain things like that, so that’s where PIDs come in,” Stewart says.

They’re also the force behind activities like our neighborhood’s Trunk or Treat, which drew hundreds of families from around the neighborhood last week for a safe night of Halloween fun.

“It’s anything that builds community,” Stewart says.

In the coming months, the NLHPID will solidify its advisory board and establish goals, with the hope of replicating some of the same success seen in the LHPID.

“You’ve got to start by listening,” Stewart says.