(Photo by Danny Fulgencio)

The funds are in place, and many lake advocates support this boathouse. So why hasn’t it been built?

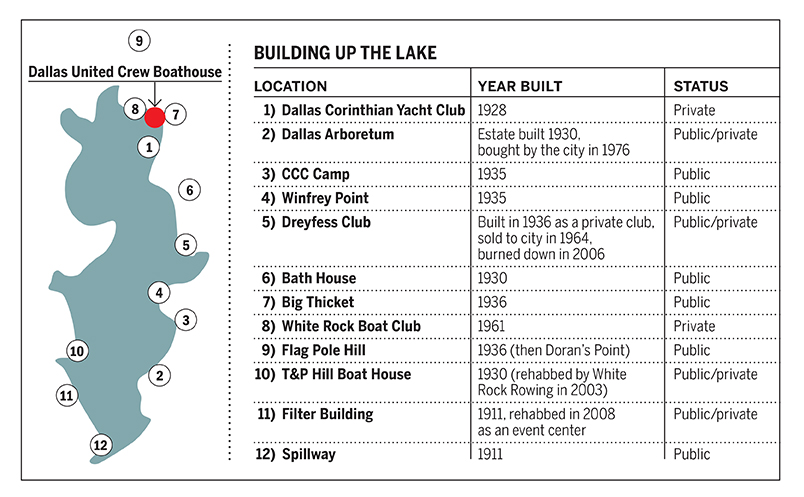

White Rock Lake is 1,015 acres of water and surrounding parkland open for public enjoyment.

Except for the spots that aren’t.

A handful of private facilities around the lake, and even upon its waters, are off-limits except to those who pay a rental fee or join a club. These private havens on public land came into existence over the course of decades, most of them before the prevailing sentiment in the neighborhoods circling the lake’s shores evolved into its current state — that public land (and water) should remain open to all.

So it’s nothing short of miraculous that the lake’s most vocal advocates, who lambasted Dallas United Crew five years ago for trying to build a watery party palace for its private rowing club, are now singing the praises of DUC’s latest White Rock Lake proposal and the inclusive way it was conceived.

The result: A kinder, gentler boathouse open to the public, floating on the northeast side of the lake, and half the size and a fraction of the original version’s cost.

The new idea seems to have won over all of the original naysayers — except one.

Councilman Mark Clayton finds himself at odds with his own political appointees and concerned about “selling off” a part of the lake.

This month, the project heads back to the White Rock Lake Task Force for another review and chance for public input. The future of the DUC boathouse — and perhaps all future development on and around the lake — hangs on the question of who and what defines “private” and whether building anything on the lake sets a precedent that can’t easily be undone.

The other rowing team

This story has been told before, when another crew team on the other side of the lake faced the same problem.

Boats have long been a staple on White Rock Lake; the boathouse at T&P Hill was built on the southwest side in 1930, where crew teams launched in the 1980s.

That was about the time John Mullen got into the sport. As the co-founder of The Container Store and an architect by trade, he knew how to build big things. Working with partners Sam Leake, David Payne, Chip Northrup and Keith Young, Mullen wanted to bring rowing back to White Rock Lake in 2003.

They set their sights on the Art Deco boathouse at T&P Hill, which was used by SMU’s rowing team in the ’90s but then left to crumble. After obtaining nonprofit status, White Rock Rowing secured an agreement to rehab the building at no cost to the city.

“There were problems with drugs and crime there,” Mullen says. “We wanted to secure it and make it useful. The city respected that there was a group that wanted to take care of that building.”

Now known as “the Boomerang” because of its shape, the site quickly filled up as the sport grew in popularity. By 2008, the club was looking to expand. Eager to keep its footprint small, the group’s leaders asked the city if they could repurpose the neglected, graffiti-covered sedimentation basins built back when the lake served as the city’s main water source.

The basins are located about 100 yards from the Filter Building, a 1920s industrial brick building with an iconic tower. It, too, had fallen into disrepair, and though the city crafted many ideas over the years to use it, none carried water.

Knowing White Rock Rowing wanted the basins, the city offered a deal: Take the basins, but in exchange, fix up the Filter Building and make it profitable. The nonprofit was offered a contract to turn the run-down building into a multi-use events facility with parking; manage it, including hiring all staff; insure it; and give 10 percent of the revenue back to the city’s Park Department. The contract included a 19-year use agreement with two 10-year renewal options.

“[The Filter Building] was a big part of that deal,” Mullen says.

In 2007, WRR raised the $2.7 million in donations needed to both build their boathouse and enhance the Filter Building. Everything they did met original design standards, earning a Historic Restoration Award from Preservation Texas in 2010. The Sam S. Leakes Boathouse (a.k.a. “the Big Boathouse”) opened in 2008, right around the time the Filter Building began hosting weddings, fundraisers and business events. By 2012, the club had raised more than $50,000 for the Park Department, money earmarked for lake-based projects.

Today, Filter Building rental rates range from $500-$3,500 and are set to rise annually, meaning it should be a financial juggernaut for years to come. The funds support WRR’s operations, which includes a slew of successful youth teams, SMU Crew and adaptive rowing for injured veterans.

This successful public-private partnership could set the stage for Dallas United Crew’s boathouse, but one major difference exists between the WRR and DUC projects: existing infrastructure. It has always been more politically palatable to repurpose something built long ago than to construct anything new at the lake.

White Rock Rowing’s boathouse effort was more politically popular because it used existing infrastructure on the lake.

(Photo by Danny Fulgencio)

A floating Shangri-La

If you want to rile up the neighborhood, try building something in White Rock Lake Park without sufficient public input.

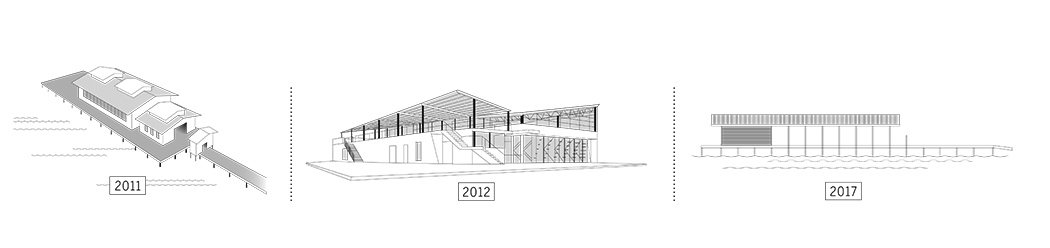

This was the case in 2012 when, after what many considered to be minimal scrutiny, the Park Board approved a contract with DUC to build a $4 million, two-story boathouse and special-event space.

Many neighbors cringed.

“The city suggested public meetings that were announced to a private email list. … The incredulous explanation was that the whole world was informed of the project and everyone was happy,” says Hal Barker, one of the most vocal critics of the original DUC project.

On the surface, it looked like DUC was following in the footsteps of White Rock Rowing at the Filter Building in 2012, but with a new structure for special events instead of a historic space.

“After an open records request, we found that the plan was for a city-sponsored adult party facility with children added, including an alcohol permit and specific use by the city for events several times a year,” Barker says.

Willis Winters, the current director of the Park Department, says the city wasn’t trying to encourage construction of a floating celebration center that would drive revenue.

“We always are looking for supplemental budget streams, but that’s not a motivator,” Winters says. “We certainly were not trying to supersize any project, especially anything on the lake.”

Ultimately, it didn’t matter. After three contentious years, the club failed to raise the $4 million needed in the time allotted. In 2015, the Park Board quietly canceled DUC’s contract, and hope for the crew team’s own space on the lake began to dwindle.

“It’s a private facility on public land. That’s old Dallas, and it’s a new day,” Councilman Mark Clayton said in 2015, soon after he became the first person living east of the lake elected to represent its neighborhoods.

DUC rowers Anders Ekstrom, Richard Zhang, Kristof Csaky, Robert Dunne, Evan Delagi and John Donahue. (Photos by Danny Fulgencio)

Still, the DUC team grew. Even though Park Cities parents started the team, its members are decidedly more diverse today, with rowers from 54 schools, seven of which are in Dallas ISD, including a full-scholarship team from Bryan Adams High School. At this point, they’re maxed out — the trailer used to store boats is full, and the men’s and women’s teams must practice on different days to accommodate the 300-plus rowers associated with the club. There’s no shortage of interest from athletes, but at this point, the youth are waitlisted.

This bothers East Dallas neighbor Tammy Adams, whose son, a Science and Engineering Magnet student, is on the varsity team. Adams became DUC president two years ago, and has seen the benefit of crew first hand. Statistics show 55 percent of female and 18 percent of male rowers go on to receive college scholarships, often to Ivy League schools where the sport is a strong tradition. DUC rowers have been accepted to Harvard, Penn, Princeton and Purdue in recent years.

“This is a sport that changes lives,” she says. “It opens doors.”

Melody Hamilton echoes that sentiment. She saw a major change after her son Frank, a Bryan Adams student, joined the team: He became focused and driven, finding a place where he thrived.

“My kid has never been more dedicated. As long as he has people behind him, he gives 100 percent,” she says, adding that team spirit makes the sport unique.

“In baseball or football, there’s always a superstar who gets singled out and treated special. The other kids get ignored. With crew, they live and die by the team.”

DUC has had three iterations of its boathouse design, but now favors the most scaled-back option because it’s popular with neighbors. (Illustrations by Brian Smith)

DUC president Tammy Adams is passionate about what rowing can do for youth, especially when it comes to scholarships. (Photo by Danny Fulgencio)

The jambalaya of peace

Adams hates the term “boathouse.” She sees it as a dirty word after the scuttlebutt that surrounded the former failed project. It’s an “equipment facility,” she says.

Currently, the team’s pricey boats sit stacked on a trailer in a parking lot on the northeast side of the lake, where they are exposed to the elements and frequently vandalized. Adams says the team needs a safe space to store the boats used by rowers six days a week.

It’s understandable she wants to sell the facility as small, considering the concerns over the size and scope of the last DUC project. It’s also understandable that neighbors would question any DUC effort after feeling left out of the last design process. Adams knew she had a tall mountain to climb to sell the new plan, but she’s a true Southerner who believes common ground can be found over a hot meal and homemade cornbread.

It wasn’t easy.

Many naysayers refused to take her calls when she began rallying public support in 2015. Armed with her signature jambalaya, she dedicated herself to proving that DUC’s committed to hearing out critics and mitigating their concerns.

“Ted and I suggested the DUC folks should look at the current sailing clubs in that area and copy the design and construction methods to provide a facility that fit the location,” Hal Barker says of himself and his brother, both longtime White Rock Lake watchdogs.

“No party barge, no alcohol sales, just a bare bones facility where they could store boats and get on the lake. We bluntly stated that anything like the previous plans would certainly be rejected by the community. So they did. At probably 10 percent or 15 percent of the original proposed costs.”

The Barker brothers were just two of dozens of former opponents to whom Adams reached out, including heavy hitters in lake politics such as Michael Jung, the White Rock Neighborhood Association president who sits on both the White Rock Lake Task Force and the Dallas Plan Commission, and Becky Rader, a member of the Park Board and president of the White Rock Lake Task Force.

Instead of a $4 million center, the club worked with architects to create an open-air, 18-foot-tall, 8,300-square-foot facility at a price tag of $350,000. It includes a public dock to be used by anyone, along with a locked and covered storage area to protect the DUC equipment.

“This was done the right way,” Rader says. “They listened and came up with a project that we could get behind.”

DUC currently launches its boats from a dock, which floods regularly in the winter, on the southwest side of the lake. (Photo by Danny Fulgencio)

DUC’s proposed location on the northeast side of the lake just south of White Rock Boat Club — the site of the former Snipe Club, where sailboats were launched from 1935-95 — is part of the reason many like the project. Like White Rock Rowing at T&P Hill, it means revitalizing something that once was instead of adding something new.

“It could be grandfathered in since boats have been in that location before,” Rader says.

The team also listened when neighbors said they wanted DUC to be good stewards of the lake. The club organizes regular cleanups and has hauled hundreds of pounds of trash away from the lake. The group’s efforts earned them the Presidential Volunteer Service Award from the Dallas Park and Recreation Department and the Lake Star Award from the local nonprofit For the Love of the Lake.

Adams says the speed with which DUC reached its fundraising goal is proof the project has community support.

“We raised $350,000 in four months because people believe in our mission,” she says.

It seems the only thing DUC hasn’t done is win over Councilman Clayton, whose District 9 includes the neighborhoods that circle White Rock Lake.

What is ‘private’?

“To be honest, I don’t like anything that involves selling the lake,” Clayton says. “It’s not a public asset if the public doesn’t own it.”

He looks to the Corinthian Club and White Rock Boat Club, both of which charge members a fee to dock boats on water out of reach of the public. Then there’s White Rock Rowing’s properties, which are also only accessible to members.

“I shouldn’t be put in this position when we have another boathouse that’s supposed to be public but isn’t really public,” he says.

But Clayton gives Adams credit for doing “the impossible” and finding common ground between lake advocates and securing the funding needed. He agrees the team needs a place to safely store boats, and he’s impressed with the team and the doors crew can open.

“Where I see the public benefit of this project is the capacity for local kids to have a fast-track to scholarships,” Clayton says.

But is that enough of a public benefit to fork over a piece of something so precious?

Clayton says he hasn’t decided yet. To get behind the project, Claytons says he wants a contract that would hold the team to certain yet-to-be-defined standards and allow the city to take the property back if DUC doesn’t hold up its end of the deal.

“Let’s say the key is community service. How do we lock that into a contract?” he says.

“The question I have to answer is, ‘Is the community better served in having this project?’ I’m not sure, but [DUC] has done a good job of getting community support, so I know I need to make a decision.”

Despite the consensus built on the water-based project at the former Snipe Club spot, Clayton says he wants to see more options before he’ll consider approving anything. Most recently, he has asked DUC to consider building on land, something Adams says would not be popular with neighbors.

“Honestly, it would save us about $70,000 to build it on land, but that’s not the right thing to do,” Adams says. “That’s not what the community wants.”

While the land options have not yet been vetted, Adams says the proposed locations would mean taking down trees or building in one of the lake’s few parking lots or somewhere teens would have to navigate the 60-foot boats across the crowded pedestrian path to reach the dock. Beyond that, Jung says the White Rock Lake Task Force has concerns about building anything on land around the lake.

“There have not been new buildings added to the lake in decades. If we allow this, then when the restaurants come …,” Jung’s voice trails off. “It sets a precedent.”

It’s why Jung says he’s against any land-based option, a point he has made clear to Clayton.

Clayton bristles a bit when asked why he is pushing for more options when there’s already a project that got the blessing of his Park Board and Plan Commission appointees, Rader and Jung, respectively, along with the White Rock Lake Task Force.

“With all due respect, I am the council member,” he says. “I wouldn’t be doing my due diligence if I didn’t consider every option on land.”

Like Jung, he’s concerned about setting a precedent. But more so, he’s concerned about any perception that the lake is for sale.

“At the end of the day, it’s a private club that wants a piece of a public asset,” Clayton says.

Jung disagrees with that assessment.

“The only thing that will be private is the locked equipment center,” he says. “I don’t see that as privatization of the lake.”

The boathouse options will be discussed on Aug. 8 during the White Rock Lake Task Force meeting at 4 p.m. at Big Thicket.