These rides are anything but average

Some might joke these neighbors have oil instead of blood and a mechanical pump where their hearts ought to be. What many of us see merely as modes of transportation, they view as motorized miracles that might encapsulate engineering marvels or bygone eras. They don’t mind the extra effort their cars demand because they’re keeping a little piece of history alive with every nut and bolt they save. It’s worth the time and expense, they say, because it allows them to live another life every time they climb behind the wheel.

The prodigy

Ricky Estrada is quick to point out he’ll be 17 by the time this article publishes, but he speaks with a passion and maturity well beyond his young years.

“I feel like, with newer cars, there’s no humanity in them. They’re all designed by machines,” he says. “Older cars, they were drawn up in someone’s head. It’s someone’s vision.”

Estrada has always been drawn to vintage things, from clocks to vinyl records. Aside from a few modern conveniences like a cell charger, his room is reminiscent of what you’d find in a 1970s teenager’s bedroom. So when it came to cars, no one was surprised when the modern mechanisms failed to draw his attention. It was vintage Volkswagons that first caught his fancy.

Estrada has always been drawn to vintage things, from clocks to vinyl records. Aside from a few modern conveniences like a cell charger, his room is reminiscent of what you’d find in a 1970s teenager’s bedroom. So when it came to cars, no one was surprised when the modern mechanisms failed to draw his attention. It was vintage Volkswagons that first caught his fancy.

“It started with the Beetle. Every time I saw one of those spunky little cars, I fell in love,” he gushes. “It was the unique shape. That’s always been my personality. It was

more these cars are different, and I wanted to be different.”

He was definitely different. He says other students at his Richardson High School weren’t clamoring for the ultimate compact car. But his love of Beetles led to an overall fascination with VWs, from buses (the 1960s split window, not the bay window-style of the 1970s) to the sporty Karmann Ghia. Estrada was 15 when he started scouring the internet for the right Volkswagon for him, something that would stand out. While there were many cars on the market, most were “farm fresh,” as the gearheads say, and needed extensive mechanical work after being left to rot in the elements for decades.

“You have to be patient with these things,” Estrada advises.

Finally, a family friend found the unexpected, but perfect, vehicle right here in our neighborhood. The cherry red 1971 VW Type 3 was just sitting at the corner of Mockingbird and Abrams with a “for sale” sign.

“I thought it was the coolest thing ever,” Estrada says. “Out of all the unusual Volkswagons, this is the most unusual.”

First manufactured in 1961, the Type 3 wasn’t introduced to the United States until 1966. Despite being the first mass-produced car with an electric fuel injector, the vehicle failed to capture an American audience, and production ceased in 1973.

After finding such a rare make in good working order, Estrada was eager to bring Rosie, as he would name the Type 3, home to his parents’ L Streets house. That’s when the teen learned the joys and pitfalls of classic car ownership.

“I knew nothing [about repairs],” he says. “There was a lot of YouTube videos and a lot of trial and error.”

Working with his dad and relying heavily on vintage car message boards online, Estrada taught himself to work on the suitcase-style engine of his Type 3. When something broke, he figured out what it was and how to fix it.

“That’s the best thing about vintage cars, they’re never perfect, there’s always something they need. It’s almost like they have a personality,” he says. “It’s almost like someone you take care of.”

He became obsessed with restoring the car to its original glory, and remains noticeably bothered by modern additions others have made, specifically the inaccurate tailpipe. Although his car was originally a dull brown, Kansas Beige to be specific, he’s much happier with its current color, even if it isn’t factory authentic.

“I like the red a lot more — it pops,” he says.

Estrada wasn’t just in love with his car, he fell for the whole culture around it. He noticed tons of vintage cars as he cruised around White Rock Lake, and got an idea.

“I thought, ‘What if we got all these people together?’ I want to hear what they have to say,” he remembers.

A simple post on a neighborhood social media page asking other vintage car owners if they wanted to get together was all it took. White Rock Car Club was born. Estrada partnered with area businesses such as Neighbor’s Casual Kitchen and Rooster Hardware to host car shows that include live music, raffles and other activities designed to draw a wide crowd.

The club has allowed him to get to know others who share his passion, although he admits he’s usually the youngest car owner by at least a decade. But that never seems to matter when they’re talking shop.

“Like every car guy, I have a list of cars I’d love to own,” he admits, listing European models like the Tatra T87, Citroën DS and, of course, a Karmann Ghia. He can’t afford those quite yet, so right now, he only has eyes for Rosie.

“I’ve only seen one other Type 3,” he says. “A guy with a Beetle offered to trade me, but that car is too special to me.” —Emily Charrier

In his best Doc Brown pose, Jaime Sendra steps out of his 1980 DeLorean DMC-12. (Photo by Danny Fulgencio)

Street art

Everything that surrounds Jaime Sendra is impressive. Colorful blooms and foliage line his long gravel driveway, the pinnacle at which presents a picturesque view of White Rock Lake. A playground worthy of a public park and the remnants (a bouquet of Mylar balloons) of a grandchild’s recent birthday party occupy a sprawling yard.

Warm greetings flow as the 72-year-old briskly makes his way to the gate. He shakes hands and asks a few questions; he responds generously to the ones posed to him. Within a few minutes it is understood that his parents were Mexican, by way of Barcelona, Spain, and that his father founded Bimbo Bakery, now a multinational billion-dollar company. And that Sendra didn’t really want to be in the bakery business. He was an artist, a graphic artist, with a pioneering mindset. He came to America in 1968 to study, met his wife, Peggy (“There were bells in the hills the first time I saw her,” he says, his Spanish accent adding a lyrical lilt), and moved back to Mexico for a few years before returning to start his own graphics company, which, with ingenuity and hard work and his brother’s partnership, made him financially successful in his own right. His parents’ story would be enough for a movie, he says, but that’s not why we are here.

The tour begins behind the first garage door, with a burgundy 1957 Mini. It resembles a shiny, big-ticket toy, a movie-set prop. Sendra — a man of above-average stature — looks borderline cartoonish sliding into the driver’s seat. Then he starts the engine, revs it several times, cranks open the sunroof and hollers over the thunderous reverberation, “See, it sounds good, right?” Turning it off, apologizing for the smell of petrol and exhaust fumes (actually an exhilarating aroma), he says, “And she drives like — oh man! When I take it to the track, my nephews, one has a McLaren, the other has a Lamborghini Diablo and the other has a Ferrari Competizione, and this little car …” He affectionately taps the Mini’s rooftop for effect. “Beat them all [pause] in the first 3 seconds. I say, ‘one, two, three,’ and then they pass me so fast I cannot even see them, but for another 3 or 4 seconds, in the mirror.” He chuckles and adds, “This car is so tiny but it’s the most fun car ever, and, I am old, but I will say, girls love this car. I am driving with my brother and the girls say, ‘Oh what a cute little car!’ ”

Mini is both charming and fierce. In fact, in Ron Howard’s movie “Rush,” about real rival racecar drivers Niki Lauda and James Hunt, Hunt’s everyday car of choice is a light blue Mini.

Even truer objects of obsession, at least in mainstream culture, are behind door number two, past a backyard tennis court, in the “car garage.”

Entering under a “Classic Car Drive” sign, Sendra explains that he’s a movie buff and therefore, “I like movie cars. The first one is James Bond [a pristine Aston Martin from the Daniel Craig Bond era] and the second is ‘Back to the Future.’ ”

Almost every child who watched the 1985 Robert Zemeckis flick was compelled to revere the magical time machine central to its plot: the DeLorean DMC-12.

For an ‘80s kid, it is surreal — sitting in the leather seat, reaching for the hand strap that pulls shut the gull-winged door, staring at that odometer, which shows 85 as top speed (that’s right: no time/space-bending 88 mph on the odometer), a regulation that began in 1980. A state trooper did once clock him cruising at closer to 100, Sendra says.

For Sendra it is a car’s aesthetic design that most draws him. He’s a curator of aerodynamic, clean-lined, functional pieces of art. Other car enthusiasts, like his brother, who was a rally racer when they were kids in Mexico, cares more about the engine, muscle and performance. That’s not to say Sendra has much use for cars without some kick — “Go ahead, start it up,” he says. “Press the gas. Again.”

The Aston Martin roars; its driver is inside the belly of the beast. —Christina Hughes Babb

A woman’s place? Behind the wheel

The year 2016 emerged a surge of United Kingdom-based blogs reporting that the number of female vintage car buyers had increased by 40 percent; females were supposed to count for 11 percent of vintage car owners by the end of last year, according to a poll by a classic-car insurer there. Here in the United States, data showed no such increased interest among American women.

Gina Cammarata, owner of a ’57 Chevy Bel Air Sport Coupe, can corroborate, anecdotally, at least, the stats. “I am often the only female at the car show,” she says.

Some men look at her skeptically, “like, OK, what’s she doing here,” she says. On the other hand, she has met some interesting people and made new friends since joining the classic car club and competing in shows.

People love vintage cars for a variety of reasons. You likely won’t ever find Cammarata working under the hood or getting her hands greasy. It is the era’s style and design trends, be it cars or clothing and accessories, that beckon her interest, says Cammarata. She wears her strawberry blonde hair curly, a wide black belt at her waist over a snug sweater and full skirt. And behind the wheel, her Ray Ban Wayfarers over her big brown eyes, she channels the archetypal ‘50s starlet.

People love vintage cars for a variety of reasons. You likely won’t ever find Cammarata working under the hood or getting her hands greasy. It is the era’s style and design trends, be it cars or clothing and accessories, that beckon her interest, says Cammarata. She wears her strawberry blonde hair curly, a wide black belt at her waist over a snug sweater and full skirt. And behind the wheel, her Ray Ban Wayfarers over her big brown eyes, she channels the archetypal ‘50s starlet.

Her father loved cars and constructed radio-controlled planes from scratch. Assembling model cars with her dad became a favorite pastime. She grew especially enamored with a challenging, large-scale 1957 Bel Air

Sport Coupe. Building together, she acquired her father’s penchant toward patience and attention to detail. As the tiny parts bonded, so did father and child.

They built other models, but this ’57 Chevy, which she painted black, was her favorite. In fact she kept it, even storing it atop the refrigerator for preservation, after her father was gone. It immortalized her dad, in a way.

In 2009, Cammarata was surfing the internet, looking at retro items for sale on eBay, she says. She went to ’57 Chevys, she says, which had recently been on her mind.

She came across a ’57 Black Bel Air for sale. She could hardly believe it, she says, “It was nearly identical to the model.”

The guy who owned it the preceding 25 years wanted to swap it for a convertible version, she explains.

“All of the numbers matched,” she says, “People who know cars will know what that means. And it had just over 89,000 miles.”

Every piece of the car, except the wheels, is original. She even has the initial 1957 Inspection sticker and, in the glovebox, the owner’s manual: The 1957 Guide to your New Chevrolet. Even the booklet —mid-century orange gingham graphics gracing its cover — is in strikingly good shape, complete with pages explaining cigarette lighters, ash trays and the electric clock, plus instructions for the breaking-in period, during which “the car should not exceed 60 miles per hour over the first 500 miles.”

“It’s not a fast car,” she says, “but a cruiser.”

Windows down on a spring evening, the Chevy glides along a road near White Rock Lake, and every passerby pauses to check her out. Any who happen to lean in to greet Cammarata would take note of what’s in the backseat — the miniature edition she built with her dad all those years ago. —Christina Hughes Babb

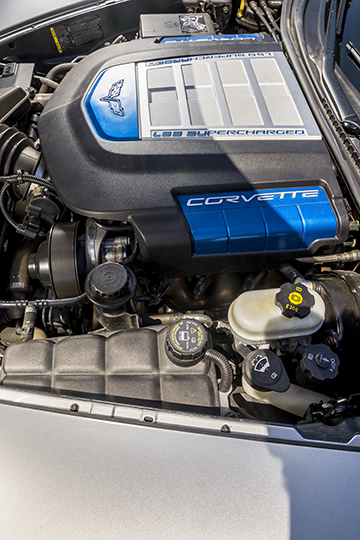

The Corvette’s engine is signed by its builder, J.D. Dickerson. “I love that a redneck built it,” Short jokes. (Photo by Danny Fulgencio)

Speeding down memory lane

To be clear, Alan Short is a smart man. He comes from intelligent, business-savvy stock. In fact, his father developed real estate throughout the White Rock and Lake Highlands area, including the 7.5-acre center at Plano Road north of I-635. That’s where Short parks — in a captivating queue at which passersby unabashedly gawk — his three most-prized possessions. When he begins to speak in southern drawl about his cars and how much he likes to speed, however, it is impossible to not, for a moment, envision Will Ferrell’s loveable yet idiotic character from the NASCAR comedy “Talladega Nights: The Ballad of Ricky Bobby.”

The comparison elicits a laugh from Short who charitably returns one of the film’s famous lines: “I wanna go fast!”

Speed is the purpose of his recent purchase, a 2010 ZR1 Corvette with a 638 horsepower engine. To quote Car and Driver magazine, “It is loud and fierce and terrifying when you want it to be, and a compliant transport unit when you’re just trying to get your tired body home.”

“I hit 160 in the HOV lane the other night,” Short says of the silver ‘Vette, a 55th birthday gift to himself. “I love to go fast. I’ve managed to keep her off the guardrail so far.”

From here, Short’s character runs fathoms deeper than the fictional speed racer. His fondness for the Corvette has roots in his friendship with his oldest brother, who introduced him by way of a 1996 LT4. The thrill of hitting 155 miles per hour was unforgettable. Years later, when his brother died, he commemorated that ride with a “155” tattoo.

Alan Short and his father worked together to revamp a 1928 Ford, now known as Buttercup. (Photos by Danny Fulgencio)

He rolls up one sleeve of his black T-shirt, which he wears atop denim, frayed-at-the-knees shorts, to reveal the ink. He dips his head fleetingly — eyes hidden behind dark specs and under the tip of a taupe cowboy hat — then lifts his chin, wearing a big grin.

“She is Lynnette, the sexy sexy Corvette,” he says. “She’ll get you in trouble but you keep going back.”

Short’s trio on display offers a trip through time.

The 1970 Monte Carlo SS 454 is innovating in its attention to both beauty and power. As Hemmings Magazine notes, “muscle car aficionados … rank the Monte Carlo SS high on the short list of personal luxury cars that tout performance at the very core.”

Like most of his cars, the Monte Carlo sort of “found me,” Short says. A friend of a friend was selling, and Short fell fast for the deep-red beauty, which he calls Christine. The Monte Carlo’s injuries, bumps and bruises always seem to “heal” easily, he says, like the regenerating ’65 Mustang in Stephen King’s novel of the same name.

The most meaningful and striking car in Short’s collection, however, is also the slowest, maxing out at about 60 miles per hour. It is Buttercup, a 1928 Ford Model A, also the oldest and rarest of his collection.

Short’s dad had a fascination with old Fords. When he heard about a family liquidating its recently deceased patriarch’s collection, Short went to check it out. When the adult son (obviously no car guy) tried to start up the ancient coup, the engine would not cooperate. Short confesses he had an idea what the problem was but kept quiet with a lowball offer, which the seller reluctantly accepted. It took Short about 30 minutes to have the prohibition-era gem running.

In the leather backseat today is a photo of Short’s dad behind the wheel — hair gray, eyes twinkling and wearing an ear-to-ear smile.

“We spent a lot of time working on this car together before he died,” Short says.

Of his 11 cars and trucks, Buttercup is the foremost showstopper. For instance, “I had a lady, like 80-something years old, stop me in the parking lot to tell me how when she was a little girl, she and her brother rode across country in a car like this, riding the rumble seat, or as some call it, the ‘mother-in-law-seat.’ ” He yanks at the rear and exposes a miniscule, uncovered chair that could fit two children, albeit uncomfortably.

Another time he exited a restaurant to find a family posing for photos around his car. “They had the little girl standing here,” he says, slapping the fender. “When I came out, they started apologizing and offering to pay me.”

A fussier owner might have suffered a coronary, but Short just laughed. “I like that people get enjoyment from it.” (Though, in general, he doesn’t recommend randomly placing children atop vintage vehicles). The Model A is sturdy and practical, constructed from wood and steel; Ford offered a floorboard hand crank in case of engine trouble and sold a kit that allowed the owner to convert the car into a tractor in a time of need.

“One day I watched this little boy, just 4-5 years old, and he just could not take his eyes off of it. He just stared and stared. He didn’t know what it was, but he knew he was looking at something special,” Short says. “That kid’s a car guy, I thought. It’s in your DNA, you don’t become a car guy, you are a car guy.” —Christina Hughes Babb