Lake Highlands elementary schools have experienced substantial enrollment growth since 2010, nowhere more so than White Rock Elementary. (Photo by Danny Fulgencio)

The untold story behind RISD’s decision to forgo boundary changes and expand the district’s fastest-growing elementary

Regeneration in full swing,” states a slide from Templeton Demographics’ January 2012 report, trying to answer the question of why Richardson ISD had experienced such substantial enrollment growth in a single year.

Regeneration is the term demographers and planners use to describe an area “turning over,” so to speak. For a neighborhood full of single-family homes, it’s when longtime residents move out and new, generally younger residents move in.

Most of Lake Highlands’ residential neighborhoods were built in the ’60s and ’70s. By the 2000s, RISD had the highest rate of over-65 tax exemptions in the state. So demographers watched the area, wondering when the families who originally established the neighborhood would move out.

It happened almost all at once between 2010 and 2011. Maps showing the lots of residents who had an over-65 tax exemption were colored in one year and nearly wiped clean the next. What the demographers had been projecting for years was finally occurring, says Tony Harkleroad, RISD’s recently retired CFO.

“It’s like predicting it’s going to rain,” he says. “If you predict it long enough, it’s going to be right.”

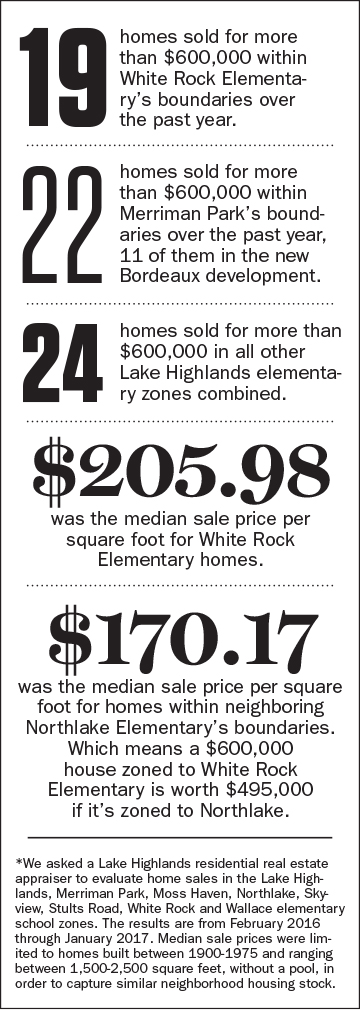

Instead of the 500 students Templeton had predicted would enter RISD between fall 2010 and fall 2011, the number was 1,000. The most significant jump was at White Rock Elementary, which had 589 students in 2010 and 926 today — and is projected to have more than 1,000 by fall 2018.

“It happened a little sooner than they thought it would and to a greater degree than they initially thought it would, and then it just snowballed,” Harkleroad says.

Voters had just given RISD $170 million in the May 2011 bond election, the third since 2001, when RISD launched a 20-year plan to systematically upgrade aging facilities and technology. The prior two had focused on renovating schools built in the 1950s and 1960s; this one would target the 1970s.

None of the money, however, had been allocated for new schools or classrooms.

The district, however, had an ace in its back pocket: Officials had been setting aside surplus funds since 2007 in anticipation of further cuts in state funding. This money now had an explicit purpose. Between 2012 and 2016, RISD added 78 classrooms at 13 schools “to accommodate enrollment growth and allow as many students as possible to enroll at their attendance area school,” the 2016 bond website states.

Regeneration took place throughout Lake Highlands. Enrollment was on the rise at several campuses, and they were feeling the pinch. Of the 78 new classrooms in RISD, 52 were constructed at nine Lake Highlands schools — four at Aikin, five at Skyview, six at Stults Road, six at Forest Lane, six at Merriman Park, six at Wallace, six at White Rock, three at Lake Highlands Junior High, and 10 at Forest Meadow Junior High.

Even with these classroom additions, three Lake Highlands elementary schools are nearing capacity again — Aikin, Skyview and Wallace — and White Rock is over capacity. In terms of rapid growth, however, “the only one that jumps out at you is White Rock Elementary,” says Bob Templeton, RISD’s demographer.

He shows this in household “yield,” meaning how many students per single-family home attend the neighborhood elementary school. At White Rock, the yield went from 0.28 in 2010 to 0.46 in 2017.

“That may not seem like a lot, but it literally almost doubled in six years,” Templeton says. “The six-year change in most elementary zones is pretty flat.”

Determining a cause for this is somewhat like “Monday morning quarterbacking,” Templeton says. One reason could be the affordability of housing, he says, even though “they’re not cheap, but for that area, it’s a great value.”

Determining a cause for this is somewhat like “Monday morning quarterbacking,” Templeton says. One reason could be the affordability of housing, he says, even though “they’re not cheap, but for that area, it’s a great value.”

More likely, though, it has to do with White Rock’s similarity to Tanglewood Elementary in Fort Worth, another school district that hires Templeton to make demographic projections. Tanglewood is an older school in a historic area of Fort Worth that is beloved to its community, and it, too, has higher-than-normal yields, he says.

“It’s a sacred school, and it’s very difficult to either peel off the boundaries or change things,” Templeton says of Tanglewood.

White Rock, too, is a sacred school, he says, describing it as having the “Field of Dreams” factor.

“For schools like this, it may be the awesome culture, the parents or PTA, the staff or principal. It can be the student body as well. It can be formed in many ways,” Templeton says. “The building is not the factor; it’s the nostalgia of the area” that makes a school sacred.

As enrollment rose at White Rock and throughout Lake Highlands, RISD “overflowed” some students away from their home schools as classrooms were maxed out, but the district’s classroom construction and commitment to not change attendance boundaries kept most students in their neighborhood school.

“Keeping those historic boundaries the same was a priority” for both the board and the community, Harkleroad says. “By adding onto those schools, we accomplished both of those objectives.”

For the most part, the boundaries were formed when the neighborhoods formed. RISD officials say the only time in the district’s history that a school’s attendance boundary has changed was when a school opened or closed.

The last three elementary schools built on the outer edges of Lake Highlands primarily affected families living in apartments. Neither Forest Lane Academy, which opened in 1999, nor Thurgood Marshall, built in 2005, have any single-family homes within their boundaries. Both schools serve northern Lake Highlands’ copious multi-family complexes. Constructed along Forest Lane and Audelia Road for young, predominately childless, professionals during the ’80s tech boom, things changed after the Walker Consent Decree in 1985 required apartment owners to make 20-40 percent of each property affordable to low-income Dallas residents. Around the same time, new housing laws made it illegal to restrict rentals to adults. Coupled with the tech bubble burst of the early ’90s, these northern Lake Highlands apartments became low-income housing for families with young children. Audelia Creek, which opened in 2003, mostly serves this demographic, too.

RISD hoped the classroom additions would contain the growth. They have, and are expected to, almost everywhere. But White Rock continued to exceed the demographer’s calculated predictions, and parents warned the district that a crisis was looming. In March 2016, the board formed the Lake Highlands Reflector Committee to address the growing problem.

Regeneration was no doubt the culprit for enrollment growth throughout Lake Highlands. White Rock Valley in particular, a neighborhood somewhat “hidden” behind Flag Pole Hill with vogue mid-century architecture, had the “it” factor that made it a desirable place to live.

The teardown trend rampant across Dallas also took hold in White Rock Valley. The 1,500- to 2,500-square-foot homes built in the neighborhood’s infancy began giving way to houses upward of 3,000 and 4,000 square feet. Price tags shot up, not just for the houses but for each square foot, making the White Rock Elementary area more expensive and exclusive than its Lake Highlands counterparts.

It didn’t hurt that White Rock was the only Lake Highlands elementary that had experienced significant demographic changes since the 2008 recession. The still unrealized Lake Highlands Town Center at Walnut Hill and Skillman broke ground in 2007, tearing down several low-income apartment complexes to make way for retail and residential construction.

In 2006, before the apartments disappeared from the landscape, White Rock had 585 students — 47 percent white, 30 percent black and 20 percent Hispanic, with 42 percent of students at an “economic disadvantage,” according to RISD records. Enrollment dipped when students from those apartments, zoned to White Rock, moved to other neighborhoods, but by 2010 the school had repopulated with 589 students. Four years later, however, the demographics were starkly different — 70 percent white, 11 percent black and 15 percent Hispanic, with only 19 percent of students economically disadvantaged.

By fall 2015, enrollment had grown to 877 — 75 percent white, 8 percent black and 11 percent Hispanic, with only 10 percent of students at an economic disadvantage.

This was the reality as teachers, principals, parents and community members from all of Lake Highlands’ schools were appointed to the Reflector Committee, whose charge was to settle on “a long-term solution to address enrollment growth in Lake Highlands.” Options included everything from adding on to existing campuses to a new elementary campus to new fifth- and sixth-grade campuses.

The number of elementary-age students coming from each White Rock Elementary home has “almost doubled” since 2010, says Richardson ISD’s demographer. (Photo by Danny Fulgencio)

The conversation always included redrawing attendance boundaries but never as a solution. Lake Highlands was experiencing enough growth that simply redistributing students wouldn’t solve the long-term problem, committee members believed. White Rock Elementary’s overcrowded state similarly was a focus, but not the main focus.

No obvious direction emerged from the committee, and strong consensus was absent, but in the end, the two solutions members liked most were building a new elementary school or constructing a fifth- and sixth-grade campus adjacent to Forest Meadow and Lake Highlands Junior High.

Before these were recommended to the board, RISD purchased a 4.5-acre piece of land at Walnut Hill and White Rock Trail. Harkleroad told the committee at one of its final meetings, “How that property is utilized does not need to be decided now, but [a kindergarten through sixth-grade school] is an option. RISD has evaluated other sites in Lake Highlands and there are very few pieces of suitable land available.”

After RISD closed on the property, the board announced in June that it would open a new elementary on the site in fall 2018. Boundary changes were inevitable. The proposed school was situated within the attendance zone of White Rock Elementary, the school that was most in need of relief and no doubt would be most impacted by the boundary changes.

The board planned to present new boundaries in mid-September, but before it could, a group calling itself “We Have a Voice” formed to oppose the new school. White Rock Elementary homes found a letter taped to their front doors with reasons for opposition, the first and foremost being:

“The attendance boundaries for elementary schools will be redrawn. How they are redrawn will be entirely up to the RISD board members.”

Though supporters also emerged in the form of a group calling itself “We Need a School,” opposition from the White Rock community continued to mount, and by November, the board had abandoned plans for the new school and hired a consulting firm, Stantec, to “work with RISD and the White Rock community to re-evaluate options to address WRE’s extensive enrollment growth,” Superintendent Jeannie Stone wrote in a letter to White Rock families.

This time around, the district surveyed only families within White Rock’s attendance boundaries.

Once again, there was no consensus, but the most popular option among White Rock families was to expand White Rock Elementary’s existing campus. This is the recommendation Stantec gave the board in February, based not only on support from roughly one-third of survey respondents but also on “guiding principles” given by RISD.

Rebalancing the boundaries of Lake Highlands schools was a close second, but when Stantec gave its recommendation, Stone suggested the district follow the consultant’s lead, and the board seized the opportunity to put the issue to bed.

Boundaries won’t budge, a new school won’t be built, the kindergarten to sixth-grade model won’t change. Construction on a larger White Rock Elementary will begin immediately, in time to open for the 2018-19 school year when the school is expected to cross the 1,000-student threshold.

In the end, RISD decided to give White Rock parents what most had wanted all along — static boundaries moreso than an enlarged elementary school. Parents at “sacred schools,” Templeton says, are difficult to sway.

“They’re so passionate about their schools, and I want them to know there are more important things to be stressed about than going from one great elementary school to another,” he says. “The reality is that the kids are adaptable — it’s the parents that have a tough time, not the kids. I don’t know how to help them to get to, ‘It’s not the end of the world.’

“The school district is trying to do what’s best for the entire district. It may inconvenience you or disrupt your schedule, but it’s needed for the greater whole.”