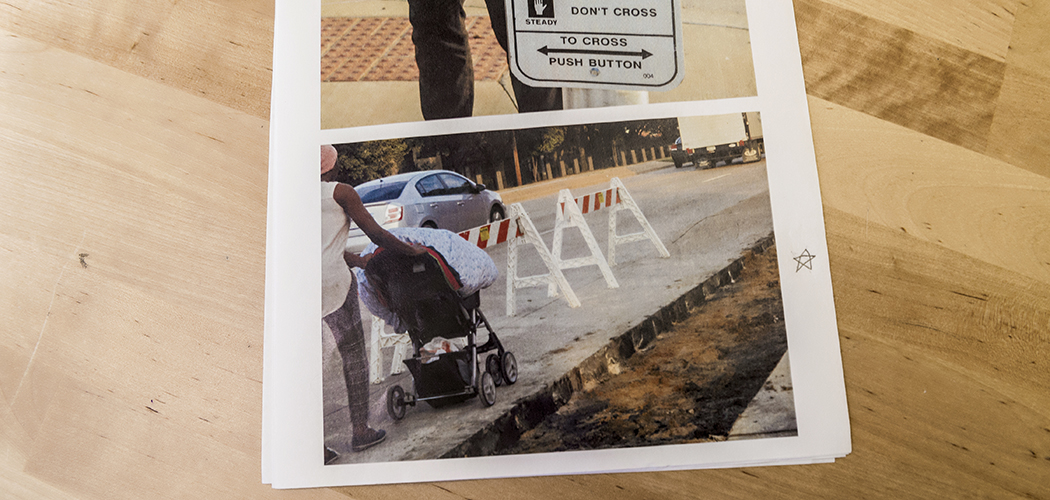

Syncier, the young photographer explains this photo by saying “The woman and baby had a hard time getting around the holes,” he adds, “Unsafe.”

Photo by Danny Fulgencio

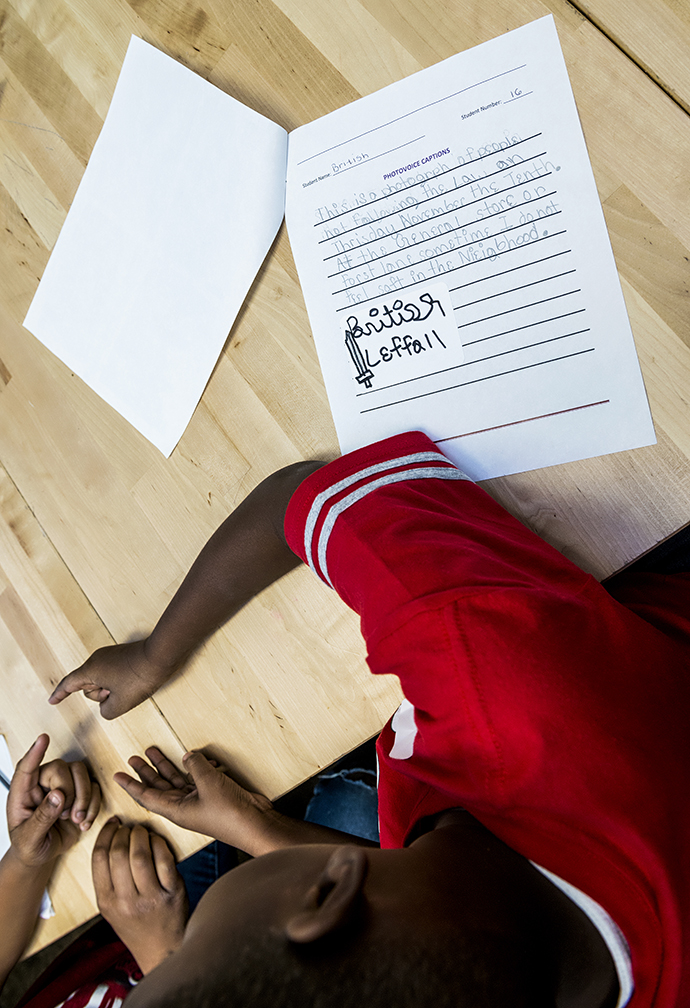

Sixth-grader British, a resident of The Vinyards at Forest and Audelia, discusses his photos, which portray potentially perilous situations. Photo by Danny Fulgencio

Children from the beleaguered Forest-Audelia area, armed with cameras, are documenting and speaking up about the everyday things that frighten them. If they go about it the correct way, they could make their neighborhood safer, say the adult volunteers who are helping them.

The photo in one boy’s hand, slightly out of focus, displays a crowd loitering in front of double-glass doors. A penciled caption reads: “This shows people not following the law at the general store on Forest Lane. Sometimes I do not feel safe in the neighborhood.” British, the 10-year-old boy who captured the image, points out the alleged rule breakers. “This guy is smoking something,” he says. “This one has a gun, and that is even worse.”

It is too grainy to tell if British is correct regarding the firearm, but the man in question does appear to be gripping an object half-concealed by the front of his loose-fitting jeans. It’s a reasonable supposition; the neighborhood has long been listed among the Dallas Police Department’s high-crime hotspots. (The DPD announced last fall that a newly formed Forest-Audelia task force helped knock the sector from the top 10.)

British and his classmates are not strangers to guns and violence, they say. British is among 10 students who live in The Vineyards Apartments at the intersection of Forest Lane and Audelia Road taking part in a 12-week project called PhotoVoice, which combines photography with social action.

They all are members of Kids-U, an afterschool initiative embedded in several Dallas apartment communities where families and working parents tend to dwell. Lake Highlands is home to seven of 10 Kids-U sites, says Lake Highlands resident Diana Baker, who co-founded the nonprofit in 2002.

Here at The Vineyards, Parkland Hospital’s Injury Prevention Center and Southern Methodist University (including a grant from its Embrey Human Rights program) teamed with Kids-U to document parts of the neighborhood in which the children feel safe, and where they do not.

“When you’re trying to get something fixed where you live, you are advocates,” says Katherine Yoder, a former aide to Gov. Rick Perry who now works as Parkland’s government relations vice president.

“You really worked for the governor?” interrupts a girl. And the children inch their chairs closer to Yoder, who nods and smiles.

“You have a voice,” Yoder tells the kids. “It’s even stronger when you come together with multiple voices, backing an issue, and evidence. Your pictures are evidence, proof.”

Photographers Hillsman Jackson and Jennifer Crenshaw donated time to teach the children how to use cameras to photograph their desired scenes and subjects. After walking the area snapping photos, students wrote about what they saw. A boy, Syncier, shows his photo of a mother and child walking near a deep construction ditch. “The woman and baby had a hard time getting around the holes,” he explains. “Unsafe.”

Volunteers teach students photography and social action through PhotoVoice. Photo by Danny Fulgencio

While one student’s photo shows two ladies jaywalking (“unsafe!”) another depicts a woman crossing at the pronounced crosswalk at Forest Lane Academy. “This is safe,” declares the photographer, Ameer. They write captions so they know what to say, so they don’t get nervous or ramble, when it comes time to speak to the Dallas City Council, which is what they hope to do in the end.

“First, we would like to get a representative here, so they can practice. We haven’t gotten that far yet, but eventually the goal is to present our work downtown,” says Parkland IPC representative Shelli Stephens-Stidham, who also takes a few minutes to address appropriate use of social media, which can be useful in activism, she says.

Before they can present their work, the kids must pinpoint their cause and desired outcome. SMU outreach coordinator Suzanne Massey is on hand to help them plot problem spots — on a map, green dots mark areas they like, yellow represents areas in which they do not feel safe, and red dots signal student-identified “do not go here at all” areas, Massey explains. This will help prioritize safety issues they might ask the city to tackle.

Now several weeks into the project, the group of Aiken Elementary and Forest Lane Academy students listens as Yoder explains that they should dress and speak respectfully when addressing city officials.

However, she says, “They are people, just like you and your parents. In fact, they work for us, for you, and if they do not respond, your parents — and someday you — can vote against them.”