It is summer in Texas, our world is a sauna, everything’s sticky. The urge is fierce to cannonball into the nearest pool, splash around and soak up its chilly reprieve.

Since the early 1900s — through wars, economic booms and busts, and desegregation — citizens and city officials have sought to satisfy this aquatic yen.

As we wade into another sweltering season, neighborhood residents are bolstered by the Dallas Park and Recreation Department’s updated Aquatics Master Plan, which promises a sunny future for local swimming. Funded by its $31.8 million sale of Elgin B. Robertson Park at Lake Ray Hubbard last year, the park department anticipates major upgrades to nine of Dallas’ 17 existing public pools, including the one at Lake Highlands North and nearby Tietze Park. It’s a remarkable feat, according to former City Councilwoman Angela Hunt, who points out that as recently as 2014, the city intended to shutter both.

The plan at the time was one-size-fits-all and failed to take into account the varying popularity levels of neighborhood pools across the city, Hunt notes; she credits neighborhood residents with speaking up and city officials for listening and responding with dramatic changes to the program.

That passion for public pools has been evident throughout our city’s history, and it’s no wonder — pools have made Southern summers bearable, even downright enjoyable. Our approach to public swimming reflects the tensions and transformations our city has experienced.

“We did everything on the lake. We swam there. We took a lot of picnics down to the beach,” says Delores “Dee” Knight, who graduated from Woodrow Wilson High School in 1954. “There was a lot of ‘parking’ that went on there at night,” she adds with a blush.

For 23 years, families from across Dallas flocked to White Rock Lake’s bucolic banks, sunning themselves on the sandy beach or cooling off with a swim — Norman Rockwell couldn’t have painted a more iconic scene.

White Rock Lake boat races. (Courtesy of the Dallas Municipal Archives, City of Dallas)

It was kept as pristine as possible, intended as a water source for the city, not a swimming hole. But when Lake Lewisville was completed in 1929 as a larger reservoir, Dallas immediately made plans to turn its 1,015-acre lake into a recreational paradise. The Bath House opened in 1930, along with the bathing beach and boathouse. There on the eastern edge, a cement slab extended a hundred feet into the lake with 500 feet along the shore, making it the largest swimming pool in the city, according to “A History of Dallas Parks,” a manuscript kept in the city archives. Attendance often exceeded 100,000 per summer, even though sanitation always had been questionable. The water was chlorinated, first by boat and later through a pipeline. Historic images also show lake-goers wading in the spillway, under a pedestrian bridge that no longer exists, at the water’s southwest edge.

Despite periods of bleak economic conditions, families found affordable fun at the lake, which flourished with recreation from swimming to sailing to seaplanes.

The U.S. Army soon saw the value of the land, building its extensive Civilian Conservation Corps camps, which included two concession stands, camps, trails, picnic grounds and bathrooms, many of which are still in use today. Flush with funds from President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, Army Capt. Tom B. Martin oversaw construction beginning in July 1935, which brought an estimated 3,000 youth to live and work at the camp during its seven years in operation.

When America joined the allied forces of WWII in 1942, the camps became a training facility for the Army, before German prisoners of war were brought to reside there in 1944-45.

After the war, Southern Methodist University bought the camp for student housing — imagine if those walls could talk. Their stories, of which few were recorded, ended when the basic wooden buildings were either sold off or torn down in the post-war boom years.

In addition to the Army, private businesses and clubs capitalized on the urban oasis, offering a wide swath of water activities, from cruises to waterskiing. Speed boating became popular and many prominent citizens built their own boat houses with a measly annual lease of $1, according to Sally Rodriguez’s book “Images of America: White Rock Lake.”

By 1952, the city determined that the boathouses unfairly limited access to the shared recreational resource and they were torn down.

When a severe drought hit Texas in summer 1953, White Rock’s water again was needed to support the city and swimming was outlawed, a ban that has remained in place ever since.

Dee Knight can’t remember the reaction from friends upon news that their summertime playground would be shut down, “But it couldn’t have been good,” she notes. “It was the end of an era.”

Today, water sports are still enjoyed on the lake, albeit it in limited capacity — barges have been replaced by kayaks, speed boats by crew rowers.

Tension lingered throughout the 20th century and perhaps beyond. Still, the Dallas Park and Recreation Department efforts during integration launched Dallas into something of a sparkling period for public pools. Families from all neighborhoods — of all racial and socioeconomic backgrounds — could spend summer days dunking themselves in an affordable, accessible public pool.

It began with the pool at Fair Park in 1925, then Tietze Park in 1946 (the first community pool near our neighborhood, built at a cost of $40,000) then, following a temporary stall due to the Korean War, Samuell-Grand in 1953. In the late 1950s, the park department built at a rapid pace — the 1958 bond package provided funds for McCree pool in Lake Highlands, along with Kidd Springs, Red Bird, Bonnie View and Churchill. Bond packages in 1962 and ’64 did not provide for any new community pools, but dozens of junior pools and wading pools sprouted.

Proof of Dallas’ love for its pool system is in the attendance record, which climbed to a high of 731,227 in 1957 according to park reports. Historic city records (which stretch only from 1921-58) show that the only year the city lost money on its pool system was in 1929 and 1930 following the stock market crash that plunged the country into the Great Depression. Even in 1943, when the entire pool system was closed down on July 2 amid a polio outbreak, the city still managed to make a profit of $2,956.

n 1973, Dallas had 100 public pools. By that time, the park department had started building the modern recreation buildings we see today, such as Lake Highlands North, known at its inception as Skyline. In 1984 the Dallas City Council announced plans to close six pools, including Griggs, the first area pool for black residents. Another 16 cut their hours.

By 2000, the city was offering free days to entice more people into the pools. Then, it switched focus entirely, investing heavily in “spraygrounds.” With contraptions that shoot, spray and dump water in all different sorts of ways, they were cheaper to maintain because they don’t require lifeguards, and a 2003 voter-approved bond showed residents were in favor of the idea.

Today Lake Highlands North pool has the highest attendance of any pool in the city, councilman Adam McGough said when calling for improvement funds. Last year, 16,590 swam there, up from a low 748 in 2005. Strong attendance has historically saved Lake Highlands North pool from the city’s axe.

In 1994, for example, when the city shuttered four of its 22 remaining pools, Lake Highlands North was never considered for the chopping block because it was the most popular pool with 20,254 swimmers according to city records. Nearby Tietze drew only 8,132 that year and was considered for closure.

Years before it closed, “the popularity of White Rock Beach began to decline. It was not a very dependable swimming place. In fact, it was just a recreation center. You know, go see and be seen and play in the sand,” Houston said. “Sanitation was always questioned.”

When White Rock beach closed, swimming’s modern era, which began in ’45, was just evolving in Dallas, progressing during a time of desegregation and accompanying unrest.

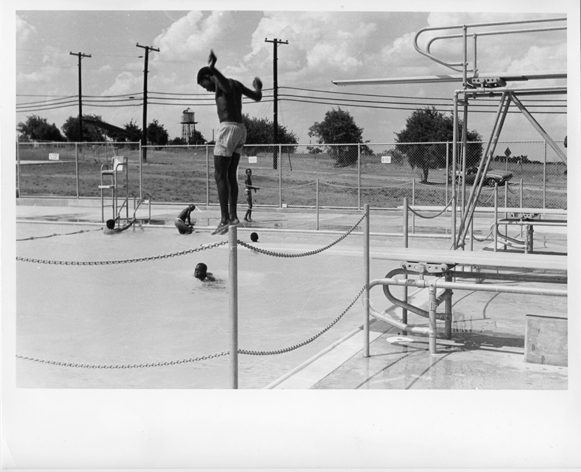

Children swim at the Hampton Road Negro children’s swimming pool in August 1955. (From the collections of the Dallas History & Archives Division, Dallas Public Library)

Swimming pools became a flashpoint for racial contention, notes professor Jeff Wiltse in his book, “Contested Waters: A Social History of Swimming Pools in America.”

“Racist assumptions that black Americans were more likely to be infected with communicable illness” inflamed opposition to racial integration, Wiltse wrote.

Also, gender mixing at pools was relatively new, and white swimmers objected “to black men interacting with white women at such visually and physically intimate spaces,” he adds.

Across the country, stories emerged of young black men being beaten for attempting to swim at white pools.

“In my book, I have pictures of black Americans who lie still on the ground with bloody heads from being pummeled, just for trying to access a swimming pool,” Wiltse said in an NPR radio interview.

Houston and members of the Dallas park board understood the perils.

“We could see the time when racially mixed swimming would be with us,” Houston said. “We had the feeling that the very last thing that white people would tolerate would be mixed swimming. We thought it would be dangerous, you know, perhaps mob violence.”

In Dallas, no written rule of racial segregation at park property existed. Rather, segregation was socially enforced, according to the park department’s centennial history. “Black citizens risked harassment or worse for using white facilities.”

Aside from White Rock and other lakes, a couple of large municipal pools served Dallas swimmers in the early 1900s.

The nearest pool for black residents of Northeast and East Dallas was Griggs Park, the city’s second black pool after Exline, located south of Southern Methodist University, almost to Downtown Dallas. Prior to 1924 it was called Hall Street Negro Park and was renamed for Rev. Allen Griggs, a freed slave who became a minister and newspaper publisher.

Imbalance in amenities grew increasingly evident over the years.

A 1944 Dallas Morning News article reported that the city offered 60 acres of park for its 60,000 black residents. In contrast, 5,000 acres were reserved for its 320,000 white citizens.

Compared to other Southern cities, Dallas managed to make a relatively peaceful transition to integrated pools, according to Slate, who co-wrote a paper with current park department director Willis Winters about the desegregation of Dallas parks.

In their essay, “A means to a peaceful transition,” Slate and Winters credit Houston with leading “a quiet revolution that was a bright spot in an otherwise tumultuous time in the city’s relationship with its black citizens.”

Park board members Ray Hubbard and Julius Schepps worked closely with Houston, according to Slate, “within the confines of institutionalized segregation to encourage the peaceful transition to an integrated park system.

Houston explained in his oral history how he and the board devised a new public swimming program while gradually integrating.

They developed a grid system of communities, both black and white, with a swimming pool at the middle of each. These smaller pools would progressively replace the existing large municipal swimming facilities.

The idea was directly tied to equal rights and desegregation.

“Houston surmised that providing more pools in more neighborhoods would distribute them more equitably throughout Dallas while reducing the chances of confrontation,” note Slate and Winters.

Houston began keeping close track of the racial makeup of Dallas neighborhoods relying on employees who lived in transforming neighborhoods for information. He plotted data about racial trends and attitudes on a map hung in his office, which he used to make desegregation decisions.

“I never will forget the day [Schepps] called me and said, ‘L.B. are we ready to mix?’ By that time I think we had six or maybe nine pools. I told him my opinion that some could and others, doubtful,” Houston said in his oral history.

When it became clear a neighborhood was nearing a black-majority population, the local park was closed for a month and reopened as a “black” park. “By that time, most whites had moved on, and the park had been peacefully transitioned,” according to Houston’s oral history.

“This method was used successfully for both Lagow and Exline parks, which served South Dallas neighborhoods that had seen some of the most violent responses to integrated housing in Dallas’ history,” according to Slate and Winters. It was employed around the city, arguably resulting ultimately in equal amenities for black citizens.

(From the collections of the Dallas History & Archives Division, Dallas Public Library)

Years later Houston would have to defend the park department’s seeming silence on issues of integration.

A trade magazine called Amusement Business noted in 1961 that Dallas desegregated parks, golf courses and other recreational facilities but explicitly left public pools out of their agreement with civil rights leaders.

Houston defended his board’s methods, which, he pointed out, were supported by the Negro Chamber of Commerce and other local black groups.

“You were doing everything you could to prevent open rebellion. Because we were living on a powder keg. And when and if a revolt had ever been precipitated well, gosh, no telling where you would have ended up.”

Was it right to perpetuate socially segregated facilities? “No,” write Slate and Winters in their paper. “However, as agents of change from the inside they realized that whatever they could do from their positions would benefit a larger movement, and that anything that could prevent violent confrontation was better than the alternative.”

Photo by Danny Fulgencio

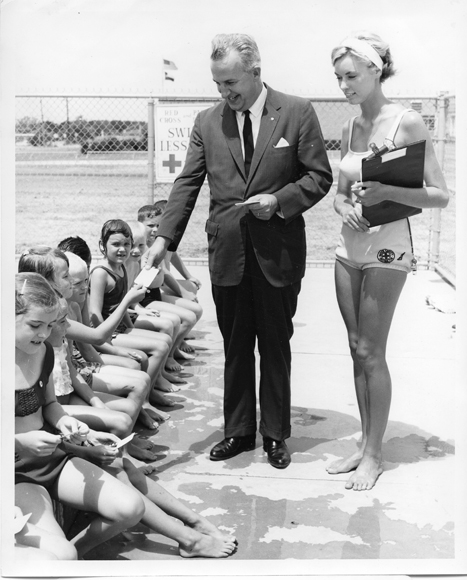

Every summer for the past five years the YMCA of Dallas has taught minority children — 60 percent of whom cannot swim, they say — basic water safety skills through its Urban Swim Initiative. A component of the Urban Swim initiative is the Make a Splash program, which brings swimming lessons to neighborhood apartment complexes. In 2011 the effort resulted in 1,900 children in 27 apartment communities learning to swim. The next year, certified YMCA instructors taught twice as many. “Safety in and around water is an important issue for all children, but studies show that there are a disproportionate number of drownings among minority children,” YMCA President Gordon Echtenkamp said in 2012. “The Y established Urban Swim to focus on decreasing the number of swim-related fatalities in minority communities by providing swim lessons to children at no cost.” The Y also runs the Urban Swim Academy to “increase the number of minority youth that are certified as lifeguards and trained to save lives in pools, lakes and waterfronts.”

Children line up for swim lessons. (Courtesy of the Dallas Municipal Archives)

The City of Dallas has long tried to compete with the private sector in offering refreshing recreation. In the 1920-50s, it built dozens of pools, making the cool waters that were once only accessible to the wealthy something attainable for average families.

Prices to enter public pools have always been low, ranging from 50 cents to $3 before the year 2000, when the city enacted a summer of free swimming. The temporary program resulted in an attendance boom, according to a 2000 Dallas Morning News article.

Attendance at pools peaked in the 1980s, before budget restrictions led to shorter swimming seasons and reduced daily hours. In 1984 the city announced it would close six pools that recorded low attendance over that summer. Lake Highlands pools McCree and Skyline (Lake Highlands North) remained open, showing “robust attendance,” according to The Dallas Morning News. In 1994 the city closed four more of its remaining 22 pools. Other pools would scale back services. The department needed to cut spending, according to the Dallas Morning News, and the closures saved the city about $65,000. The park department at the time offered neighborhood children free transportation from the closed pools to the nearest open pools a few days a week, the article said, reporting also that the most popular pool in the city that year was Lake Highlands North, which drew about 18,000 swimmers.

In the 1990s, around the nation, aquatic centers and spraygrounds were gradually replacing traditional municipal pools, notes Kimley-Horn Associates, Inc. in its Aquatic Facilities Master Plan for the City of Dallas, which it updated last year. “Changing pool trends and health codes, competition for recreation time and dollars, and the advent of the commercial waterpark all have impacted attendance and operational sustainability at old style pools,” note the consultants. In the 2000s, Dallas built spraygrounds that offer a more water park-inspired experience than a traditional public pool.

In fact, Lake Highlands North Park is home to one of the region’s most popular public sprayground. Built in 2006, its success is a product of partnership between the city and corporate, individual and nonprofit sponsors such as the Lake Highlands Junior Women’s League, which raised tens of thousands of dollars for extra sprayground amenities. In 2007 the trade magazine Athletic Business plugged it as a model for the nation. In an article about Dallas replacing pools with more cost-effective spray parks, Dave Strueber, assistant director for the park department’s west region, called the Lake Highlands sprayground “a huge magnet for that community, where folks from all over the city are coming now.” He added, “We want to model the rest of our spraygrounds after Lake Highlands North.”

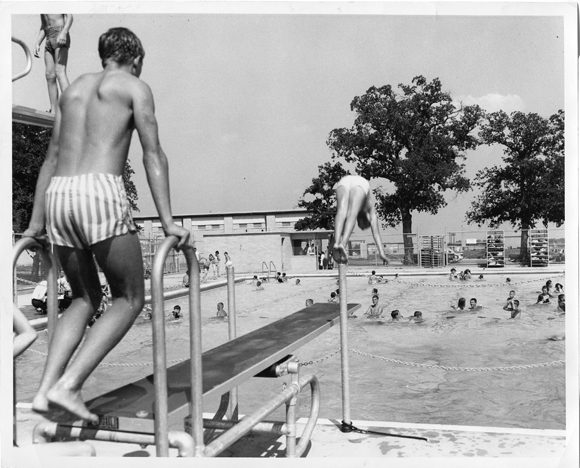

A happy lifeguard and swimmers at McCree Park pool in May 1969. (From the collections of the Dallas History & Archives Division, Dallas Public Library)

Ridgewood Park, just south of Northwest Highway, also opened its sprayground in 2006 and it was such a success, the area was flooded with traffic. By 2008 “residents only” parking signs lined nearby streets.

Today our city has set its sights on aquatic centers. Part neighborhood pool that can offer the traditional swimming lessons and camps; part water park with slides and other fun features, the new designs aspire to entice families looking for all the bells and whistles while also filling a basic community need.

The city has money to sink into the effort, thanks to the sale of Elgin B. Robertson Park at Lake Ray Hubbard, which is funding the bulk of Dallas’ $52.8 million aquatic makeover.

In our neighborhood, that includes $3.5 million worth of construction at Lake Highlands North pool (adjacent to the famous sprayground) and, not far away, a $2.6 million facelift for Tietze Park.

Though the design of the new facilities at Lake Highlands North has not been finalized, it likely will become a “neighborhood family aquatic center” with a modern, family-friendly pool and bath house.

Swimmers take advantage of public pools in the 1950s. (Courtesy of the Dallas Municipal Archives)

Final designs by Kimley-Horn along with Quimby McCoy Preservation Architecture are expected by the end of the year, giving the city ample time to hear from residents about what they’d like to see. The city last year and in early 2016 solicited public input via neighborhood meetings. Tree preservation, security, exercise programming for children, seniors and families, and affordable pricing are among the things Lake Highlands residents listed as highly important. Designers aim to begin construction next year and to open the newly refurbished Lake Highlands Neighborhood Family Aquatic Center in May 2019.

In fact, in the 1920s, two attendants, a male and a female, were assigned to each pool, enforcing rules that allowed boys (ages 7 to 14) to swim from 4 to 5 p.m., while girls had to wait for 5 to 6 p.m., according to the 1921-23 Parks and Playground System Annual Report produced by the city.

In the late teens and early 1920s, the City of Dallas put a huge investment into its parks department, building 10 wading pools all over the city at a cost of about $3,200 each (or $40,000 in today’s dollars). What’s more, each of those 3.5-feet-deep pools had to be drained, cleaned and refilled with 35,000 gallons of water daily, creating extensive work for the city’s maintenance department.

But no one can say the citizens didn’t love and use the pools. Wading pool attendance was listed at 9,333 at Exall Park from May to September in 1923, while Buckner drew 9,348, according to the report. That works out to more than 65 swimmers a day in the city’s first micro-pools. So popular were they that they kept building them, and by 2000 had amassed a collection of 26 sprinkled across Dallas parks.

Lake Highlands North community pool. (Photo by Danny Fulgencio)

That was the year the Centers for Disease Control cracked down on wading pools, after a child in Atlanta died from contracting E. coli after swimming in one. While larger pools are built with filtration systems to keep them clean, wading pools run the risk of becoming breeding grounds for bacteria in the stagnant water, even though it was changed daily, health experts said. In February of 2000, the parks department announced plans to close all 26 of the city’s wading pools, sparking an immediate backlash.

People were protective of their petite park pools, and vocally opposed the idea of losing them. Park officials countered that the wading pools were all at least 50 years old and would require about $4 million to bring them up to new state codes aimed at preventing disease outbreaks. Former Mayor Laura Miller was the most vocal opponent of the plan, and went about finding her own funding stream to protect four of the wading pools, specifically Arcadia Park in her Oak Cliff district. Despite the effort, the wading pools were eventually closed.

1

McCree was the most popular swimming haunt throughout the 1960s-early 2000s, fondly remembered for its high dive, free-swim sessions, concession machines and easily scalable fence, sometimes taken advantage of by rebellious teens daring a midnight dip. It closed in 2007.

“We jumped the fence and swam at night … around ’79,” notes Sondra Smith McClendon. “The drink machine dropped the little paper cup out then squirted syrup from one side and carbonated water from the other,” recalls Diane Hale Smith. “First time I ever jumped off a high diving board,” Robbie Pigg tells us. He had no air conditioning at home, so spent as much time as possible submerged. “We only had an attic fan … how did we do it?”

2

Skyline is a close second when it comes to nostalgia. It’s still open today, renamed Lake Highlands North, and it is due to receive a major overhaul next year. But way way back, opening day at Skyline pool yielded one of the most legendary bits of Lake Highlands lore: Amid opening-day frenzy — floatie-clad kiddies splashed in all four corners and every inch in between— a 5-year old girl stepped off the diving board’s edge, disappeared, and, moments later, had not resurfaced. The father of another child, watching from the clubhouse balcony, scanned the poolside. Had anyone else noticed? Deciding no, he jumped, shattering his foot in the process. He drew the attention of a lifeguard, who rescued the girl from the pool’s floor. That man was the father of Debra Oaks Pettit, a Lake Highlands resident. The little girl, now a healthy 52-year-old woman, was a friend of her sister. “They did not yet have insurance,” Pettit recalls, “so my dad paid out of pocket for his cast.”

Joanie Jordan Buster remembers being a lifeguard at Skyline her senior year, ’81. ”I hated the hideous orange swimsuits they made us wear.”

A pre-teen Suzie Luther James caught the eye of one fellow swimmer. “My husband’s very first memory of me is from the summer of 1971 at Skyline swimming pool. A 12-year-old skinny girl with a dark tan and a florescent orange bikini made a lasting impression on him.”

3

Other public pools in the vicinity included Boundbrook Park, Ridgewood, Fair Oaks, Lochwood, Harry Stone, Tietze and Samuell-Grand.

4

Residential pools came along in the ’70s. Mindy Hawley Stuart had a pool, she recalls, the only one in the neighborhood. “My dad set up a system for the neighborhood kids to come swim. He made a flag on a pole and when the flag was up anyone could come swimming but if the flag was down it was family time.” “Our neighbors down the street had a pool where we would play Marco Polo,” reports Gene Saugey. “They had a sign that said, ‘We don’t swim in your toilet. Please don’t pee in our pool.’ ” Classic.

5

Vickery Park, in the 1940s, was located near where Presbyterian Hospital is today and had Texas’ biggest swimming pool. It was accompanied by an amusement park. “The kids loved Vickery Park,” Lake Highlands resident Mark Davis recalls. “It was a big pool and there were other things to do besides swim. We used to go ride the electric bumper cars straight out of the water, which I doubt was a very good idea, but at the time nobody cared if dripping wet children got on 220 volt electric cars with shoddy wiring and bashed each other.”

6

Private pools grew popular, such as Knights of Columbus 799, known to Lake Highlands residents as the KayCee pool. It opened in the ’50s where the White Rock DART station now sits. It relocated to Northwest Highway near Ferndale in 1998. There is a two-year wait for an annual membership, which runs about $400. The Royal Oaks Country Club pool, Elks Lodge (then on Greenville, now on Northwest Highway), White Rock and Lake Highlands YMCAs, and the Jewish Community Center pools also were popular. “I practically grew up at the Elks Lodge,” Janie Pate Abraham writes. “The bottom of that pool ate the skin of my toes smooth off.”

7

Apartment pools were pretty easily accessed by teens willing to bend the rules. The one at the Village Apartments was booming. “In high school me and the girlfriend used to go to the Village and swim in the nice big pool,” says Dean Ingram. “There was hardly anyone ever there and no one ever asked us if we lived there.” King Edwards and Villa Cipango Apartments also are mentioned.

8

Beloved swimming teachers, two in particular, were mentioned again and again. “My parents, Mr. and Mrs. Adams, and I have taught thousands and we still teach through the year at our school,” notes Amy Adams. “Gene Coppedge coached at LHHS and taught summer sessions of swimming at his pool for many years,” Joyce Pittman says.“The first technique Coach Coppedge taught me was to float on my back, then pull water up along my side so I’d end up crossing the pool face up and feet first,” Amy Matlock Connel recalls. “I still do it, and it always reminds me of that pool.”

9

Creeks and natural pools were the best, recalls Phil Brockett: “We swam in the creek running behind McCree pool. There were places that got to about four feet deep with nice white rock bottoms.” According to Todd Barnes, “Behind Lake Highlands North there is a path that leads down to two tunnels, and at the end of the first tunnel, under White Rock Trail, was a pool full of crawdads. No one ever swam in it intentionally, but some accidentally took a dip. At the end of the second was Jackson Branch. We would slide down the muddy creek beds as we watched the apartments and Kroger (now LA Fitness) being built.”

10

NorthPark Inn is remembered by few. In the ’70s there was a luxurious hotel located at 9300 Central Expressway. In addition to a helipad, limousine service, and TVs and radios, the inn boasted two swimming pools, to which a privileged few Lake Highlands residents had access. “Does anybody remember NorthPark Inn?” queries Nick Stevens. “We had a swimming pool membership there when I was little.” Few chimed in, but we located a vintage postcard of NorthPark Inn, which shows two large (and one smaller, likely a hot tub) aqua-blue bodies amid a sprawling complex. Best Western owned the place. For $35 a night, families could enjoy the amenities, plus dining, dancing and $1 drinks at the resort’s Old New York Tavern, according to an advertisement in Texas Monthly.