The solutions series

Monthly in 2014, the Advocate will share a story about people in our neighborhood struggling with poverty, unemployment or other disadvantages, and we will examine efforts made to improve those difficult situations. We also will write about individuals and groups dedicated to making a difference. If you have a story to share, email chughes@advocatemag.com and write “solutions” in the subject line.

“Apartment people” and “apartment kids” — you hear these terms regularly, and often derisively, when neighbors discuss Lake Highlands’ socioeconomic differences.

Complaints about the proliferation of low-income families are common on our website, too.

“I have no patience for people who have kids they cannot afford. It’s those families — mostly Hispanic, black, refugee — who are ruining our neighborhoods, filling them kids they can’t afford,” notes “Morgan” in reaction to a story about neighborhood elementary schools.

“Apartment kids have higher rates of poor academic performance and discipline problems. My kids’ education suffers because teachers have to devote more time to these kids,” wrote a commenter under the screen name “Bad For My Kids.”

City Councilman Jerry Allen, whose district includes Lake Highlands, says that there’s “no place for that kind of talk” in Lake Highlands and that it’s counterproductive to building a stronger neighborhood.

[quote align=”left” color=”#000000″]“The lazy way is to blame all of our problems on one group of people. But success depends on effort and willingness.”[/quote]The first order of business when it comes to strengthening our community, Allen says, is changing some of the things we say about one another. Allen says he prefers the term “multifamily communities” instead of “apartments” and “experiencing asset poverty” instead of “poor” or “indigent”.

“Once people start seeing we are all in this together, we can get on our way to living in a safe, clean, more enriching neighborhood, which is what every family wants,” he says.

Examples of those “getting on with it” can be found in every nook of our neighborhood.

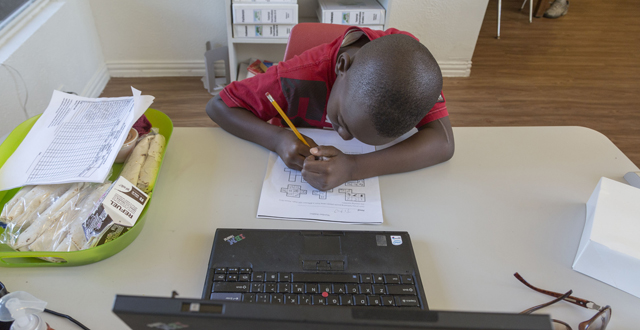

Take, for instance, Kids-U, a Lake Highlands apartment-based program focused on providing basic after-school care and tutoring for some of our area’s most vulnerable children and adolescents.

“I’ve had my bike stolen twice,” says 8-year-old Jacob, a student at Northlake Elementary and a resident at Alista, an apartment community on Royal Lane near Abrams.

“One time, while I was riding it, and the other time off my porch,” he says, working out a math problem as he briskly answers questions.

People in subdivisions with nice houses often have their things stolen, too, Jacob’s tutor says both to Jacob and the rest of us within earshot.

Jacob doesn’t dwell on the loss. He smiles politely, but he doesn’t want to chat anymore, because he needs to read.

“Twenty minutes,” he says. “Can you time me?”

Founded in 2002, the nonprofit was formed in an effort “to combat one of the most profound problems in Dallas: children not completing their education,” spokesman Brandon Baker says. He points to a study (“Today’s Children, Tomorrow’s Communities”, 2006) that shows that more than 100,000 students ages 5-13 in Dallas County are unsupervised during after-school hours.

“We believe these are the most critical hours for the student,” Baker says.

Kids-U tries to ensure Jacob and students like him have a snack, do homework and play each weekday afternoon. With supervision, they avoid risks such as substance abuse and criminal or sexual behaviors, Baker says.

A few miles away, a church called The New Room welcomes kids from apartments in the Whitehurst-Skillman area after school. The New Room opened in a run-down shopping center near Skillman and Whitehurst in 2007. A satellite branch of the Lake Highlands United Methodist Church, it’s a place that welcomes everyone, says director of community ministries Jill Goad.

Many people living in that area — one of Dallas’ most densely populated low-income regions — who want to be part of a church community find it difficult to attend services because of transportation and childcare issues or even because they feel they don’t have the right clothes, Goad says. The New Room offers a “lively, praise-filled, come-as-you-are” service, she says.

In addition to providing worship services and tutoring, The New Room partners with Network of Community Ministries — a nonprofit that offers emergency services, medical care and food to Richardson ISD families in need — to systematically deliver food to residents of the Whitehurst-Skillman area. This is just one example of the efforts many neighborhood churches are making to focus externally, says Dabney Dwyer, who leads outside ministries at nearby Church of the Ascension.

Her church — which has collaborated on community events with LHUMC, Network and a slew of other churches, nonprofits and government programs — also has a partnership with a nearby elementary school, Stults Road Elementary, where church members mentor students, host read-a-thons and have helped with facility improvements.

The collaboration of our many service-oriented organizations is key to maximum impact, Allen says, and we are doing a better job working together than ever before.

Clearly, there are people (both renters and homeowners) caught in negative behavior cycles who will not benefit from any amount of help. But we can find and focus on those who will, experts say.

“There are different needs, priorities and desires within every economic level,” says Monica Bein, a sociology specialist who led a recent poverty workshop at Ascension church.

“You cannot even take for granted that all people in poverty want to move to middle class. You have to start with the basics and offer services to those who want them.”

The solution is simple, if not easy, Allen says.

“The lazy way is to blame all of our problems on one group of people,” he says. “But success depends on effort and willingness.”

It’s not about religion, though many faith-based groups are leading the charge. There is, however, a biblical tenet driving the effort, Allen says.

“Love your neighbor as yourself. It’s that simple,” he says. “When I arrive at the Pearly Gates, I don’t think God’s going to say, ‘Who did you vote for?’ No, He is going to ask, ‘What did you do for that guy who came to you for help?’ ”

See more photos from the Kids-U program by Brandy Barham (click to enlarge):

- Northlake Elementary students who live in the Alista apartments participate in Kids-U, an afterschool program: Brandy Barham