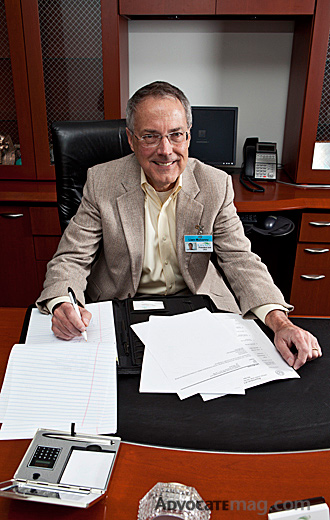

Chelsia Williams started out as a client of LifeNet, and now she is a full-time employee. The nonprofit’s clothes closet is named after her. Photo by Danny FulgencioLiam Mulvaney is president and CEO: “There is always far more need than there are services avialable.” Photos by Danny Fulgencio.

Nine years ago, Chelsia Williams’ life was a mess. She was an alcoholic in denial about a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, and she had little regard for how she treated herself and others. But she found LifeNet, a Lake Highlands-based nonprofit, for help with mental illness, and her life slowly started turning around.

Liam Mulvaney is president and CEO: “There is always far more need than there are services avialable.”

She wound up utilizing several LifeNet services, including permanent supportive housing, emergency food and clothing donations.

Now she is a fulltime employee at LifeNet, with her own apartment in the neighborhood, a closet full of stylish clothes she bought herself, a savings account and plans for a cruise-ship vacation.

“I’m just so happy to be alive,” she says. “I love myself.”

LifeNet is the city’s largest provider of permanent supportive housing, that is, multifamily housing for formerly homeless people. It also provides medical help and counseling, through its clinic on Skillman at Forest, for those with mental illness and addiction. It supplies food through a partnership with the North Texas Food Bank. And it helps people find jobs.

Anyone who isn’t familiar with LifeNet might be surprised to learn that it started 35 years ago as “Hideaway House.”

“That’s indicative of how times have changed,” says president and CEO Liam Mulvaney. “At the time, the thinking was that people with mental illness should be ‘hidden away.’ ”

The state had cut funding to mental hospitals, including the one in Terrell, which went from 2,000 beds to 300. Low-income mental health patients needed help, and they were no longe receiving it from the state. So LifeNet began.

The nonprofit’s name later changed to Phoenix House, and then in the late ’90s, to its current name. Most of its funding comes from federal grants, but about 5 percent of its $8 million annual budget comes from private donations.

LifeNet does not operate homeless shelters, but it does manage several properties in the neighborhood and around the city, housing 520 formerly homeless people. Professionals manage the properties and assist residents with everyday things such as understanding a bus schedule, as well as more complicated thingssuch as dealing with mental illnesses and addictions. The goal for many is to eventually move into their own apartments independently.

- Without his tiny apartment in the Prince of Wales building on Live Oak, 51-year-old Tracy Hamblen says, he would be lost.

Tracy Hamblen lives in an apartment building that LifeNet recently purchased on Live Oak. The building was constructed in 1913 as a destination honeymoon hotel. In the ’90s, it was a den of prostitution and drug use. But now it houses 63 men and women who needed a hand up in life.

“If you’re homeless and you have kids, there are a lot of services available for that,” says Hamblen, 51. “If you’re homeless and single, there are not as many options.”

His room in the Prince of Wales apartment building comprises about 200 square feet, including a twin-size bed, shower, sink, toilet, a few cabinets and a closet. It is modest, but a bed is the smallest measure of kingdom, and this is Hamblen’s.

Black-and-white photos of Marilyn Monroe decorate the walls. There is an outdated TV and immaculate bedding.

“I just cannot tell you what this place means to me,” he says. “I would be on the street and lucky to have a box.”

Hamblen takes pride in the building and its community. He showed talent for procuring donations when the building threw a barbecue for residents one Fourth of July. Since then, he has taken on the role of coordinator for donations.

Another resident enjoys mowing, so he is in charge of cutting the grass. Some residents fix meals in the community kitchen for those who don’t cook.

“It’s almost like a family,” says LifeNet vice president of development Ross Taylor. “The residents really take care of each other.”

LifeNet also finds jobs for many of its 2,000 clients. Not only that, the nonprofit creates job opportunities for them.

LifeNet contracts with the cities of Richardson and McKinney, as well as the Majestic Theater, WRR radio station and the Meyerson Symphony Center. LifeNet clients do all the custodial work, maintenance, litter pick-up and landscaping for them.

Even though LifeNet helps some 2,000 clients, the nonprofit is always stretched to its limits. It is not uncommon for 12 or more people to be lined up outside the clinic by 6:45 a.m. It opens at 8 a.m. and accepts only 10 walk-ins each day.

A $1.2 million loss in funding has been the result of a tough economy and government cutbacks.

“There is always far more need than there are services available,” CEO Mulvaney says.

Still, LifeNet provides hope and a lifeline for the neighbors who need it most.