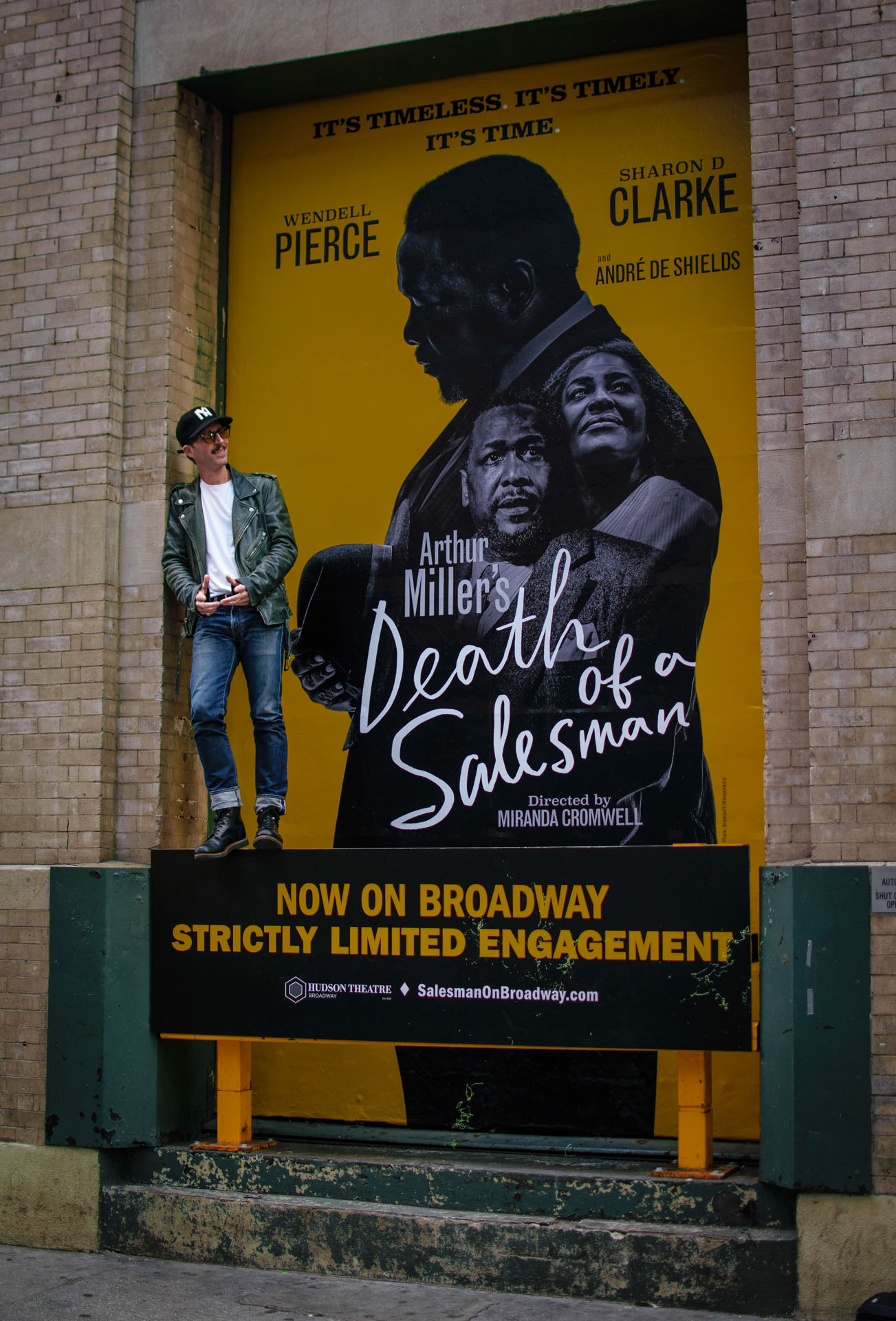

Photography by Maya Jackson

For the first time ever on Broadway, a Black man — the recognizable Wendell Pierce (The Wire, Jack Ryan) — is Willy Loman, in Authur Miller’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play, Death of a Salesman.

Lake Highlands native Blake DeLong plays two characters in the mostly white world in which the washed-up salesman operates.

DeLong is double cast as Loman’s boss Howard and Stanley the waiter.

Death of a Salesman, which premiered on Broadway in 1949, is about an aging traveling salesman’s descent into madness and toxicity as he realizes his lifelong pursuit of the American dream was futile.

The director of the latest iteration, Miranda Cromwell, brings a “notably rich” production to stage, according to New York Times critic Jesse Green.

In this version, Willy’s son Biff ’s prospective college is changed from University of Virginia to UCLA, because the former did not allow Black students before 1950. Other than that, Miller’s 70-year-old script remains practically unchanged, DeLong says.

“What they were able to do in terms of telling the story this way is nothing short of genius,” says DeLong, who, in 1995, saw Hal Holbrook (Into the Wild, Mark Twain) play Willy in Death of a Salesman at Fort Worth’s Casa Mañana Playhouse.

“It changed me, seeing him do that,” DeLong says. “I think it might be the greatest play of all time. The more time I spend with it, the more I am just in awe of what Arthur Miller did in constructing this play.”

The Times critic writes that because of the cast’s racial makeup, DeLong’s characters become more than a foil in the usual sense.

“As with Willy, you can never untangle the personal, economic and now racial threads of their behavior,” he notes of the supporting players.

Debuting on Broadway with such an ingenious and ac-claimed production is a dream come true for DeLong.

“I just can’t believe I get to do it,” says the Lake Highlands High School alumnus. “I can’t believe I get to go out and play Wendell Pierce’s boss in this crazy scene, just me and him.”

Yet his resume, replete with biting portrayals of bullies and bigots, suggests he’s a no-brainer for the Salesman parts, which, he says, reflect not overt but embedded racism in America.

Repeatedly playing unrepentant racists would be tougher were those roles not in service to the greater good, says DeLong, who has embodied, to name a few, a racist federal narcotics agent in Lee Daniel’s biopic The United States vs. Billie Holiday, a racist detective in Ava DuVernay’s When They See Us and a racist cop in Spike Lee’s Pass Over.

In Salesman, DeLong is once again a villain, but this time it’s subtler, he explains.

“As Willy’s boss, I fire Willy Loman so I’m the bad guy. It’s kind of a turning point in the play. But the character is not an outright Klansman, right? He’s a vain, ruthless person who doesn’t know he is racist,” DeLong says. “In some ways it’s more insidious. It’s 1949 and you see how it’s just understood, assumed. It’s understood that when the thing falls on the office floor, who’s going to pick it up.”

(Washington Post critic Peter Marks wrote that the subtle racism and panic in the Willy-Howard scene are “shock-ing(ly)” well-played.)

These scenes hit audiences differently than when the Lomans are white, DeLong continues.

His other role as the waiter is a tiny part, but people have told DeLong they find it interesting and kind of funny, the actor says.

“He’s a white guy serving these gorgeous, obviously successful, well-dressed (Black) guys dinner, and he’s blown away,” DeLong explains. “But it’s 1949, racism is baked into every interaction, so he’s in awe of them, but doesn’t know how to respond. I’ve been moved by people’s response to that.”

DeLong came by his success in an exemplary manner, approaching his career with realistic expectations and hard work. While studying history at University of Tex-as, he took part in his first film, Matt Muir’s Thank You A Lot, about musician Jack Hand. That led to a group of faculty members paying for his tuition if he promised to continue studying performing arts in grad school, which he did.

He took risks, moved to New York, bartended, babysat and made sales calls to pay the bills, while also facing constant rejection at auditions and elsewhere.

He recalls being fired from the call center at age 30, crying and feeling like a loser. But the next day he landed a Best Buy commercial, alongside Justin Bieber and Ozzy Osborne, that aired during the 2011 Super Bowl.

The musical Natasha, Pierre & The Great Comet of 1812 earned him a nomination for a Lucille Lortel Award, Off-Broadway’s highest honor.

In 2011’s We Need to Talk About Kevin, DeLong acted alongside Tilda Swinton, who he describes as “freakishly nice.”

Life as a Broadway actor is everything — except relaxing.

Via phone, while pushing his toddlers through Prospect Park en route to his polling station (it’s Election Day), the father of twins outlines a grueling schedule that involves taking multiple trains and long hikes through Times Square to and fro performances, leaving the theater each night after 11 and arriving home a couple of hours before the infants awake.

“The babies don’t care if you did a play on Broadway last night,” he says, adding that his wife is amazing about handling the mornings so he can sleep.

“I got a mask and earplugs. They don’t do much,” he adds before insisting that he has no complaints and describing his parents’ (to whom he attributes his strong work ethic) visit.

They came to town for the babies and the show, after which everyone hung out with stage and screen star Wendell Pierce.

“It’s just so special. I am still pinching myself,” DeLong says. “No amount of my description is going to do it any justice.”

Death of a Salesman runs at the Hudson Theater in New York City through Jan. 15.