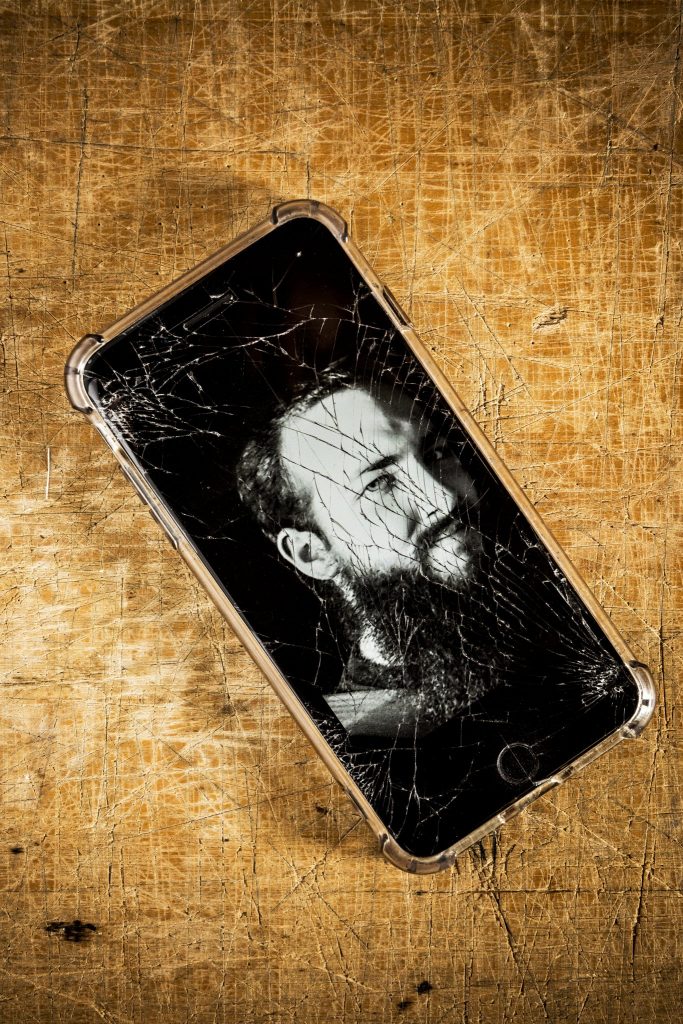

Colt Brock

Return to “Still I rise” homepage

Braxton and Colt Brock always had shared striking similarities and major differences. Colt is academic, usually clean-shaven and outspoken. His older brother grew an unruly beard and “hated” school, but he was a genius when it came to mechanics and working with his hands, Colt says. After graduating Lake Highlands High School in 2014, Braxton sought out his own social group, like-minded friends with a yearning to ride and work on bikes. Braxton didn’t go off to college, but he labored some 50 hours a week. “All he knew was work,” Colt says.

At night Braxton slept on a twin bed, parallel to Colt’s.

At 21, he and Colt, 17, still divvied their childhood room. “We shared that room, it seems like, all our lives,” Colt says.

There’s no need for twin beds in the room today.

When Colt returned at the beginning of the school year, there were few at Lake Highlands High School who didn’t know Brock had died, killed in a hit-and-run motorcycle accident in early August.

“People look at you. They don’t know what to say. There are a few people who actually do know how we feel,” he says.

Austin Silva, who died suddenly last year, was a classmate, he says.The Kampfschulte family of Lake Highlands, who lost a little boy to a rare illness, also made efforts to help Colt’s shocked family in any way possible.

Braxton was killed on his way home from work at about 9:30 on a Thursday night.

Responders told his family the driver might have not even noticed that he hit Braxton.

Colt was brushing his teeth when he heard loud banging at the front door. “Braxton,” he figured, “always trying to scare me.”

But it was two uniformed officers on the porch instructing the family to drive to a Plano hospital, where, they said, Braxton was in ICU.

Except for sister Katsie Rane, a sophomore who was away at camp, they gathered into the car.

“I knew whatever it was, I had to hold myself together, because I knew my mom was not going to be able to take it,” Colt says. “I had to keep it together.”

When Colt, mom and stepdad arrived, the physician immediately imparted the unthinkable news: “There is no chance of him waking up.”

The surgeon was blunt, Colt says.

“It seemed mean at first. It hit Mom instantly like a wrecking ball to the gut. I went into shock, I think. The words were so hard, quick, unexpected, but now I understand why,” he says.

For one thing, Braxton’s remaining organs were healthy and young, and he had always spoken ardently of being an organ donor. He didn’t drink or party, his family says, so they expected viable parts.

But they had to move fast.

“He officially died the day following the accident, Friday, and we already had the ball rolling and everything,” Colt says.

Six people received Braxton’s life-saving organs and 75 others benefited. Skin, bone, eyes — almost everything was put to use.

Braxton wasn’t the sentimental type. “I recall thinking at the funeral services, he may not have liked everyone in this room, but he loved all of them, and would have given any one the shirt off his back.”

Giving his organs was a small catharsis, Colt says.

The devastated family pressed through the pain, because they had no choice. Sister Katsie has suffered a condition called fibromatosis most of her life. Some cases are treated with chemotherapy at certain stages; in 2016, Katsie’s needed to be.

“She got sick, lost hair. Mom and my sister would go to MD Anderson hospital in Houston every Wednesday for treatments.”

But she is “a fighter;” they both are, he says of his sister and mother.

Since Braxton’s death, Colt’s stepfather has undergone a total hip replacement.

His mom eventually stopped working as a teacher and became her family’s nurse for a while. But the family is financially stable. The accident was mostly covered by the state, because it is considered a criminal case.

Braxton’s life insurance policy will go toward his siblings’ college funds.

Police still are searching for the white pickup truck, caught only in blurry images on a Plano street camera. “I can’t — none of us can — look at a white truck without thinking about it,” Colt says.

Colt used to be the senior wrestling captain but quit the team in October.

He started an architecture and design club. It is a national affiliate — so far only 20 high schools have chapters. LHHS “swept the district” at the first competition.

Colt plans to intern this summer at PBK Architects, the company that did the latest redesign at LHHS.

Eventually he hopes to earn a master’s degree in architecture. He loves the work, because it keeps his mind busy with problem solving and satisfies his creative side.

As he readies to head home for the day, the topic of facial hair emerges. In photos taken before his brother’s funeral, Colt’s face was smooth.

“In wrestling, we weren’t allowed to grow [a beard], but I stopped shaving the day of the accident.”

Now he sees a little more, even, of his brother in the mirror each day.