In 2014, undocumented immigrants living in Lake Highlands helped police find and lock up their little girl’s killer. Following the investigation and court proceedings, the grief-stricken parents learned of a federal program, the U Visa, which gives victims of certain crimes who assist in an investigation a path to United States citizenship. Obtaining one is time consuming, legally complex and prohibitively expensive. With help from a couple of his Lake Highlands High School teachers, the murdered child’s 16-year-old brother launched a fundraising effort to raise the remaining money needed to procure this special visa for his family. He wants to surprise his mom with the money, he says. She has endured so much. “She was so close to my sister. They even looked the same.”

A little girl vanished.

Several officers from the northeast police substation arrived at the Sontera Palms Apartments just past noon on August 31, 2014. As word got around, residents, many who knew the child and her family well, emerged from their homes by the dozens to join the search.

Kathrine Gonzalez was last seen playing with her dog and two other children on a grassy patch outside her babysitter’s window. Katherine’s father helped police question those playmates, who were able to name the person who lured Katherine away. Officers knocked on doors and grilled everyone in sight. At 2:30 that afternoon — based on a tip from a neighbor who remembered seeing the girl, a dog and an older boy — police entered vacant apartment 1143, where they encountered the content of nightmares. Katherine’s body dangled in a closet by a shirt around her neck.

Even before the discovery, two officers had hauled Angel Lizandro Sanches-Zenteno, the girl’s 17-year-old cousin, to the station for questioning.

Katherine’s family suspected Angel right away, says Katherine’s brother Victor Maya, now a junior at Lake Highlands High School.

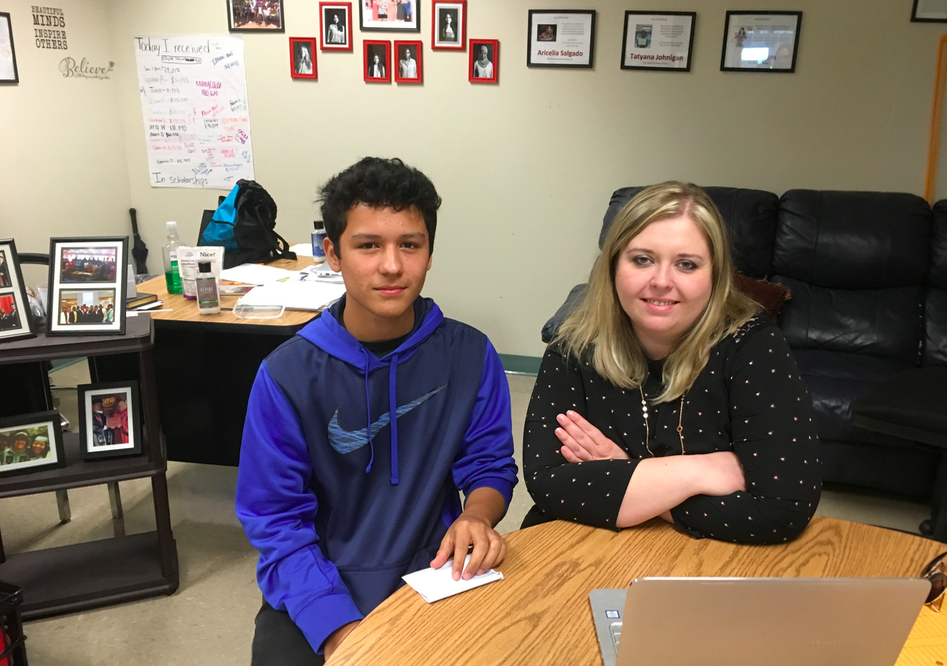

Sitting at a table in the AVID office, teacher Rhianna Anglin by his side for support, Victor — his voice soft yet sure — talks about his sister’s brutal murder and the relative who is serving a life sentence for it.

“He had been in trouble before — drugs, trying to stab someone … He pulled a gun on me once when I was a kid, and he said I better never tell anyone,” Victor says. Angel, son of Victor’s mother’s sister, had a terrible childhood. He obviously was disturbed and starved for attention, but the extended family felt more sorry for him than afraid of him, Victor says. This level of violent depravity, especially against his own family, was never anticipated, says Victor, who was 14 at the time of the crime.

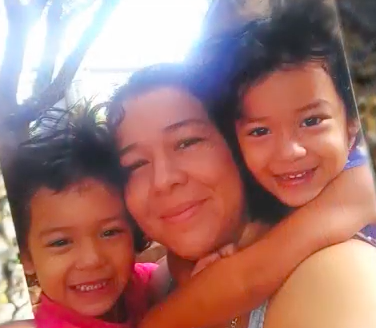

“She just had her 5th birthday. I was with her that morning, when she went missing,” Victor recalls of Katherine, a happy child with big brown eyes and a perpetual smile. “I remember going off, playing with my friends, and my dad came, asking where she was, had I seen her? And we started looking everywhere … She was my little sister. We loved each other.”

Police interviews with Victor and his parents and other witnesses helped to immediately identify Angel as a suspect and, along with DNA and additional forensic evidence, speedily build a case against him.

According to court documents, Angel eventually confessed to strangling Katherine with his hands. Found guilty of capital murder of a person under age 10, he was sentenced to life with possibility of parole after 40 years.

Victor and his parents are undocumented immigrants from Mexico.

Often such a status prevents people from cooperating with police when they are victimized or when they have knowledge that can aid a criminal investigation, because they fear it might lead to deportation.

It was the last thing on Victor or his parents’ mind. Nothing mattered except Katherine.

“We didn’t care about being deported. All [my parents] were thinking of was my sister and getting justice,” Victor says.

He and his mother and stepfather and younger siblings were treated with respect, he recalls. He received bereavement counseling through Child Protective Services.

During that time an attorney contacted his mother about the U Visa—she said they would most certainly qualify for one under guidelines set by Homeland Security’s U.S. Citizen and Immigration Services. U Visas are part of a 2000 congressional act designed to protect undocumented individuals who report certain serious crimes such as murder, rape, human trafficking, incest, kidnapping (to name a few) from threat of deportation. The annual cap on U Visas is 10,000.

Victor says that the aforementioned attorney (a woman whose name he does not know) accepted $2,000 from his parents and disappeared without finishing the work. However, once his mother learned about the possibility, she set about finding someone else to help pursue the U Visa. It took some time, but she located an immigration lawyer who could help. Better yet, once the new attorney heard the family’s entire story, he offered his services pro bono. “He was moved by it,” Victor explains. (The counselor helping the family is with the Thomas Price firm).

Victor’s biological father died when he was 3.

He can recall age 5, living with his mother and stepfather in abject poverty in Mexico. “Our house was a 600 square foot room with no indoor bathroom or kitchen.” His parents earned, respectively, 25 and 75 pesos per week, they’d told him, and “they worked all the time.” Victor says he often stayed home alone. Desperate, the adults seized an opportunity — an illegal and dangerous one, Victor now understands — to cross the border into Texas. They believed it was the only way to provide a better life for their children, he says.

They left Victor with his grandmother and an uncle while they fought to find footing in the U.S. At first they could only afford a truck, which they lived in, and after they worked and saved and had enough to rent an apartment, they arranged for Victor to join them.

That proved more difficult than they possibly imagined.

Victor was 6 years old when he embarked on the first of three attempts to reunite with his parents. He tells of his experience, drawing on a mix of memory and what he has been told by family members.

He was with an uncle (who ultimately remains in Mexico) and a small group of Mexicans using a paid coyote to help them cross a river to the American side. When the lights of the border patrol skimmed the water, the group, including their paid smuggler, scattered. Victor’s uncle, the boy clinging to his back, nearly drowned battling his way across the Rio Bravo and crawling up the muddy embankment on the American side, where authorities somewhat promptly picked them up.

Later, Victor in an exploit much like the former, made it to the U.S. side on foot. His memory is shaky, but he won’t forget his fear and hunger. “We were lost three days and two nights [in the desert] before ICE caught us.”

After that he was sent to live in an orphanage for a period of time. Then he was transported to a house occupied by more strangers. They turned out to be others preparing to attempt to cross the border.

He’s not sure how it was arranged or how it was successful, but this time he finally reunited with his parents.

Victor attended elementary school at Skyview, where he learned English.

“Everything here was like a movie,” he recalls. “Lunch lines, more than one teacher, textbooks. I started writing inside my textbook, I remember, and the teacher said, ‘no, no, no. Those cost hundreds of dollars’.”

His parents still worked long hours — mother as a hotel maid and father as a painter — but now they earned more for their efforts. Victor points out that his parents always pay taxes and never receive their tax returns, since they are undocumented.

Victor’s dad wants to start a business. His customers love him and it would surely thrive had he the residential status required to pursue the venture, Victor says.

Life was good, though, until the tragedy, he says.

His mom never could go back to work, unwilling to ever leave Victor’s two littlest sisters, twins who are now 5, or even their 12-year-old brother, with a caregiver. In a victim impact statement, she told her daughter’s murderer that she forgave him, Victor recalls, “that she knew he had a bad life” and was sick.

While Victor was a good student, he says he began to feel helpless earlier this year; with constant talk on the news about deportation, he grew despondent. His grades fell, he says, and college seemed more and more unrealistic.

Here, AVID teacher Rhianna Anglin interjects.

“They have no idea the mental anguish they put upon kids,” she says of recent presidential proposals related to immigration, which include construction of a wall along the Mexican border and potential repeal of protections for young people put in place by the previous administration. “We [educators] lose the ability to motivate them when they have no hope. It is difficult to deal with students who don’t see a way to citizenship.”

On March 17, St. Patrick’s Day here in America, Victor’s family received word from their attorney that they officially qualified for the U Visa. Amnesty was imminent, pending a few more procedural steps and filing a load of paperwork. Although the immigration attorney is donating his time, filing fees and court costs add up to about $7,000.

Victor asked his mother, “how will we get the money?” Her answer: “God will provide, Son.”

Victor reapplied himself at school, brought up his grades, started researching colleges and participating in activities including a recent student immigration forum.

Most ambitiously, he aims to raise the money that will set his family on the road to citizenship. Once they obtain the U Visa, they will receive identification and social security cards within a couple of months. That would allow Victor’s dad to follow his dream of beginning his own business.

Two to three years later, provided they do nothing to disqualify themselves (such as commit a crime) they can become permanent citizens.

Victor says he wants this for his parents, not only because of all the pain they have endured, but also “because they work really hard, and they are really good parents.” He says citizenship would give them a chance at more fulfilling work, and will give he and his brother an opportunity to go to college.

Anglin and other adults at the school helped Victor create a video and set up a Go Fund Me page. Below, he tells a bit of his story, saying at the end, “I really feel they deserve this surprise.”

Connect to the page and donate to “Victor’s Wish” here.