Gone 20 years, the texas skate king’s influence is undeniable

That treehouse on Flag Pole Hill was Jeff’s cherished reprieve from a difficult world, says Jimmy Coleman — Jeff’s friend and erstwhile business partner — the one place he could go to quench his thirst for nature, but it was nondescript, “just a normal tree with some wood planks nailed in up high,” Coleman says.

Read about the other Lake Highlands legends whose legacies refuse to die:

Horse whisperer Tex Oddson

FM radio icon John LaBella

If it’s still there (Coleman thinks it might be, although it’d be tough to find), rest assured no child can climb its rungs to perilous altitudes, because Jeff was precise regarding their placement — close enough for he and his friends to shinny up, but too far apart for little legs to reach a foothold. That’s the kind of guy he was, says East Dallas skater Woody Sigrist, who grew up skating at Jeff Phillips Skate Park.

“He cared about things like [children’s safety]. I didn’t have pads, couldn’t afford them, so he gave me some from his shop. That’s what I remember about Jeff.”

Coleman says he and Jeff and their buddies would hang out here, about a quarter-mile into the woods from, and 60-75 feet above, Jeff’s Flag Pole Hill abode, which was funded by cash competition prizes, sponsorships and sales of his Jeff Phillips signature boards, stickers, T-shirts and gear. On sturdy platforms, they drank beer and sometimes smoked joints rolled from Jeff’s “personal hydroponically grown stash,” according to Rolling Stone.

It’s no secret that Phillips indulged — he once outperformed Tony Hawk, “The Birdman,” skateboarding’s biggest name, while under the influence of hallucinogens, according to lore.

“I don’t remember that specifically but it seems entirely possible,” Hawk says. “If Jeff stayed on his board, he was tough to beat, on or off drugs.”

The White Rock Valley rental was a cozy pale-charcoal bungalow with a carport where Jeff and live-in girlfriend Alison hosted barbecues and cohabitated with several snakes, a monitor lizard named Lurch, a three-horned chameleon, a few geckos, four cats and a freshwater eel. Jeff and Alison regularly attended herpetological society meetings.

Jeff considered buying the place, which also was chock full of models he loved to construct and weapons he collected.

[quote align=”left” color=”#46b6d5″]“I don’t remember that specifically but it seems entirely possible. If Jeff stayed on his board, he was tough to beat, on or off drugs.”

–Tony Hawk[/quote]

Alison moved out in 1993, but she told Rolling Stone in ’94 that she and Jeff never officially broke up.

Unlike many of the era’s young skate stars, Jeff did not pilfer away his earnings. He invested in his dream, the Jeff Phillips Skate Park, which he bought in 1991.

Business stress along with Alison’s departure contributed to his despair, according to media at the time of his death. Tony Hawk attests that the era was the most awful time in history to try to earn a living through skateboarding.

“Skate parks were closing, skate companies were going under and vert skating, as Jeff and I were mostly known for, was considered dead,” Hawk says. “I had just started a family as all of this came crashing down, so financial pressure was ever-present.”

Jeff started skateboarding when he was 10. Bill Dempsey, a classmate at Lake Highlands Junior High, remembers his friend as a kindred spirit, a fellow daredevil who loved flying through the air, up and over ramps, hanging at Wizards Skate Park, then located near the Dallas-Richardson border.

Wizards, by the way, was the worst of the worst parks, according to Dallas’ Guapo Skate Park proprietor Al Coker, who also owned Dallas’ first skate shop at Valley View Mall in the ‘80s. That he could skate the “awful” Wizards is a “testament to how physically talented Jeff was,” Coker deadpans.

This past spring, just before Guapo closed its South Side location (Coker plans to reopen elsewhere soon) many of Jeff’s old friends gathered and reminisced about him.

Charismatic, kind, generous, fun-to-be-around and mesmerizingly talented is how they describe him. His memory moves many of these men to tears.

Hawk, speaking from California, says he first met Jeff at a competition in Del Mar, Calif., and “liked him a lot because he was clearly having fun and didn’t care about the contest element so much.”

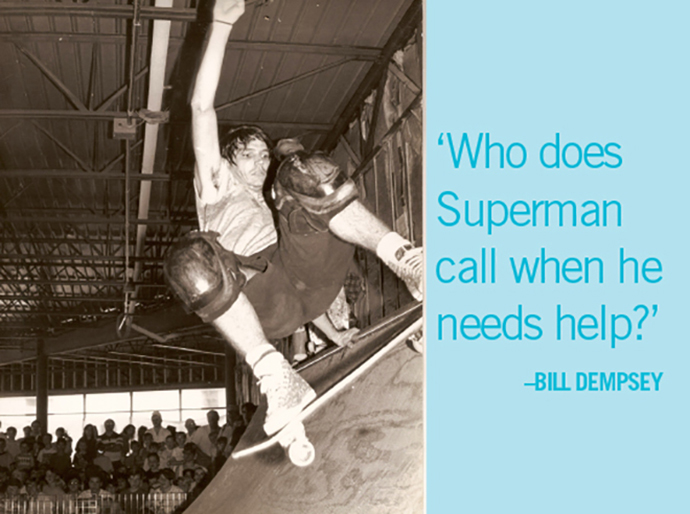

“God, Jeff was smart,” Dempsey recalls. “You had to be to gauge some of the things he attempted.”

A guy once badly injured himself following teenaged Jeff’s lead.

“At Wizard’s there was this snake run, and Jeff gets this idea, instead of going the way its meant to be, why don’t we drop into the end? Well the end is like a crazy straight-up wall that launches you up in mid air, and it’s impossible. Just take my word. Impossible. But he goes, ‘No, I’ve figured it out.’”

An older guy there thought Jeff and Bill were little punks, and after witnessing Jeff pull off this move, he tried it,” Dempsey says. “He left in an ambulance that day. We heard later he’d busted his spleen. We never saw the dude again.”

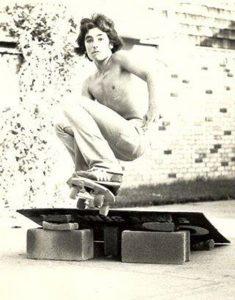

To further illustrate Jeff’s unique skill, Dempsey pulls forth a black and white photo of himself, on his board, jumping a ramp.

Bill Dempsey, childhood friend of Jeff Phillips. (Photo by Gina Natho)

“That’s taken in Lake Highlands by our friend Gina Natho, for photography class. This picture of me, I am so proud of. You do not understand how many takes it took to catch me looking like this,” he says. “It wasn’t that way for Jeff. Everything he did was right. Every shot perfect, just like another day at the office.”

Though they had drifted apart once the fame began to escalate, Dempsey says he quit skating for 30 years in the mid ‘90s, following Jeff’s death.

“Hard for me to articulate, but I couldn’t look at a skateboard without feeling overwhelmingly sad,” Dempsey says.

“He was all power. He shook the ramp and made it feel like thunder,” Coker recalls. He stops mid-sentence when he sees a guy perform a Phillips 66. “There it is,” Coker says. After building up speed driving back and forth in the half pipe, the skater rides backward to the lip of the bowl where he plants a hand, swings his body upside down, twists all the way around and drops back into the bowl — a difficult maneuver that Jeff invented and few skaters attempt.

Everybody at the park talks about Texas skaters and their reputation.

From afar, Hawk confirms. “‘F-you, we’re from Texas,’ pretty much sums it up. Jeff was Texan to the core.”

[quote align=”left” color=”#46b6d5″]“Skate parks were closing, skate companies were going under and vert skating, as Jeff and I were mostly known for, was considered dead. I had just started a family as all of this came crashing down, so financial pressure was ever-present.”

–Tony Hawk[/quote]

It’s almost impossible to imagine that this guy frequently referred to as a god and legend — who periodically graced the cover of Thrasher magazine, who appeared in dozens of advertisements and whose name alone was worth somewhere in the neighborhood of $70,000 a year by age 19 — was a virtual pariah when he started high school in 1980.

“Being a skater at a Dallas high school then meant being a distinct minority, being vilified by jocks and rednecks, as well as by parents,” wrote Peter Wilkinson in a 1994 article for Rolling Stone. “‘What are you going to do with that toy in class?’ football players asked skaters in the hall at Lake Highlands High School. Reveling in their new private rebellion, they vowed to skate forever.”

Jeff, his dad Charles, mom Hilda and older sister Kathy moved to Dallas after several years living in Asia.

Around the time Jeff began renting his house, his White Rock neighborhood was plagued by a series of driveway robberies, according to Rolling Stone, which cites the crimes as part of the reason Jeff bought a gun, to “keep at home for protection.”

A typical Texan, the article continues, Jeff had an affinity for guns and knives. In the summer before his death, the story goes, his infatuation increased, and he attended 20 gun shows in just a few months.

High school attitudes nonwithstanding, the ‘80s was skateboarding’s big boom. Skate culture flourished around the country and Jeff was a king. “I definitely took inspiration from him,” says Hawk, “and wished I had a style as smooth as his.”

For a while Jeff tried to attend Richland College, to appease his mom, but she told Rolling Stone that school was hopeless. “Skating was his life and he never outgrew it. He got hurt so many times it was ridiculous. Even after major surgery he’d get back up on that damn board,” she said in 1994.

His cohort Coleman came in to help run his 13,160-square-foot Northwest Dallas skate park. Despite support from friends and fellow pros like Hawk — who calls Jeff’s park “one of the few places I looked forward to skating on the first Birdhouse tours,” — by 1993, in the days leading up to Jeff’s suicide, they were meeting with parties interested in taking over, Coleman says. He thinks the suicide was a bad, split-second decision, which Jeff would have badly regretted.

“We all do these stupid things, especially when we’re drinking or whatever, and he just did the one dumb thing he can never take back.”

[quote align=”left” color=”#46b6d5″] “‘F-you, we’re from Texas,’ pretty much sums it up. Jeff was Texan to the core.” –Tony Hawk[/quote]Coleman adds that one of the saddest realizations is that just a year or so later, X Games and extreme sports rose to popularity; it’s where Coleman found his niche as an athlete and announcer. “If he’d been here for that he would have been dominating again,” Coleman says.

Guapo owner Coker thinks maybe Jeff had a form of clinical depression or bipolar disorder that could have been treated if he’d grown up today.

“Medicated, maybe he’d still be alive. It’s pure speculation on my part, but I think it could’ve been different,” Coker says. “I was sad. He was a kid I had very fond memories of.”

Hawk says he wishes Jeff had “found a way to stay positive in those dark times. It would be incredible to see him at the ‘legends’ events that have gained so much reverence in recent years.”

Dempsey says he understands how bad it hurts to have something you love become the source of stress. He adds that Jeff was such a hero to all that he might have felt he had nowhere to go with his problems.

“Who does Superman call when he has issues?”

Jeff and some friends spent the day before Christmas 1993 at Bennigan’s on Northwest Highway drinking $1 beers, followed by Bloody Mary’s at Shuck ‘N’ Jive on Greenville, according to the Rolling Stone piece.

That night, like every Christmas Eve, he hung out at his parents’ house in Lochwood, and he didn’t seem particularly drunk or despondent. He had dinner with his folks and sister, her children and husband. Kathy told Rolling Stone it was basically their happiest-ever Christmas dinner.

But at 2:45 a.m. Jeff went home — reportedly the first time in eight years he did not spend Christmas Eve at his parents’ place.

His neighbor Judy Walgren discovered him on Christmas afternoon, sitting on his bed, slumped over, the .357 Magnum revolver near his body.

Some other neighbors helped break into the house, and they reportedly were all praying together just before Hilda came careening up the driveway.

“Nobody’s been able to get ahold of Jeff …” Hilda clipped, mid-stride. Walgren tried to hold her, begging her not to go inside, but Hilda barreled past those struggling to restrain her, making a beeline for her son’s body and screaming, “Let me help him!”

Jeff was buried at Restland Memorial, in the Lake Highlands area, but a few years ago, after the site attracted too many visitors — fans piling skateboard wheels and plastic toys upon his grave — Jeff’s family moved him to an undisclosed location, his friends say.

The questions are unending: Why and how and what if? One thing all his friends seem sure of is that Jeff, if still alive, would be right out here with the so-called Old Man Skate Cartel.

“He’d love this,” Dempsey says, looking around Guapo Skate Park — crowded with skaters who are black, brown and white, clean-cut and dreadlocked, aged 8 to 65 — on its bittersweet closing day.

Most of these same people will gather together again later this summer for the annual Jeff Phillips tribute, which originated in 2011 and has drawn such celebrities as Christian Hosoi and Craig Johnson. Hilda and Kathy, Jeff’s mom and sister, both have attended the event, Coleman notes, a fact that initially shocked him, he says, and tugs at his heartstrings. They participated after 2014, when it became a fundraiser for the Suicide and Crisis Center of North Dallas. Through these get-togethers, as Woody puts it, “We keep his stoke going.”