We were promised a movie theater, cool new restaurants, a community grocer and a walkable neighborhood gathering place. Ten years and $23 million of public funds later, all we have is another apartment complex. What happened to the town center, and why is the developer telling us that the grand plan won’t work?

You could feel the optimism that bright November morning in 2008. City officials and developers in hardhats rallied with Lake Highlands High School cheerleaders, dancers and band members outside an empty apartment complex at Walnut Hill and Skillman.

Drums rolled. Highlandettes high-kicked. The crowd cheered. A wrecking ball careened through the top floors, walls crumbling close to where the Haven Lake Highlands apartments stand today.

Former Dallas City Councilman Bill Blaydes, who spent much of his term courting potential Lake Highlands Town Center developers, took the podium to deliver a rousing speech.

“Because of what we celebrate today, Lake Highlands will not become stagnant for our children,” he proclaimed.

Attendees responded with a standing ovation.

OK, developers are an optimistic lot by nature, but it’s been seven years since that heralded groundbreaking. It’s been 10 since a Tax Increment Financing district (TIF) was established along the Skillman Corridor to set the fiscal stage for the town center, five years since DART built its town center rail station, and one since a grocery store anchor unofficially agreed to lease a space at the town center. The land, aside of a single multifamily residential building, remains a 70-acre prairie.

Its fallow appearance belies all that has happened behind the scenes in recent years.

Our new city councilman campaigned on pledges to promote town center progress; the center is under the new management of Cypress Real Estate Advisors; the Skillman Corridor TIF — which potentially could funnel millions of dollars into the project — enjoys new, motivated board members.

But a stalemate has formed between new town center head honcho Cypress Real Estate, which wants to deviate from Prescott’s original vision, and city designers, who are pushing for Cypress to stay true to the initial concept.

By the numbers

$3.4 million

for streets, bridgework and thoroughfare assistance (Dallas County)

$5.2 million

for transit, pedestrian and bicycle connectivity and thoroughfare work

(North Texas Council of Governments)

$4.7 million

Infrastructure improvements, (City of Dallas 2006 Bond election)

$10 million

DART station and rail

$23.3 million

total public sector investment as of 2011

This recent activity indicates the project is at a tipping point and that, for better or worse, neighbors of the development could soon see some bona fide construction. Or not.

In recent months, neighbors, developers and stakeholders have been asking some core questions: Does the original vision still stand as the best solution? Will taxpayers who have contributed millions of dollars by way of the City of Dallas, Dallas County, North Texas Council of Governments, DART and TIF funds settle for something different from the original dream for Lake Highlands Town Center? And, what realistic design can succeed on this site?

The first committed developer, Prescott Realty, realized they couldn’t afford it alone. To lay the economic groundwork for the ambitious town center project, the City of Dallas created the Skillman Corridor TIF in 2005, which funnels incremental property tax dollars above a base from neighborhood commercial property owners into improvement projects identified by the city. The city designated 40 percent of the Skillman TIF to the town center — a total of $23 million — but reimbursement was tied to work completion.

Prescott’s commitment, outlined in a 2007 development agreement, was to build a dense, urban, walkable project including parking structures to accommodate shoppers and diners patronizing its 280,000 square feet of retail, those living in the 1,719 residential units and others using the 25,000 square feet of office space or 20 acres of parks and trails.

The master plan had the look of a transit-oriented development, and a successful one would rely heavily on the construction of a DART rail station.

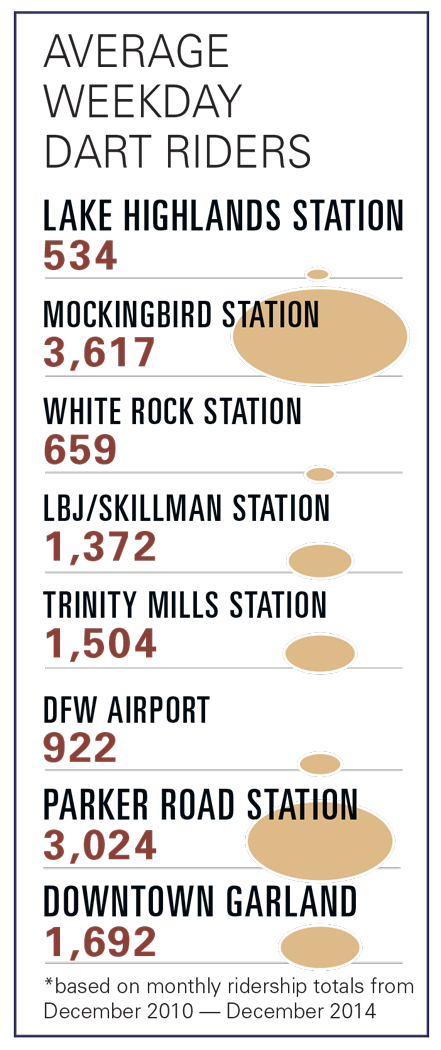

Enter Jerry Allen. Before replacing Blaydes on the city council, lifetime Lake Highlands resident Allen served on DART’s board of directors, where he championed the center’s DART station that was completed in 2010, the first infill station along an existing line in DART’s history, at an expense of $10 million. One irony is that the station was built at the same time the surrounding area lost thousands of potential riders when 1,300 apartment units were demolished to make room for the proposed town center. (See below for an illustration of Lake Highlands DART usage compared to local DART rail stations.)

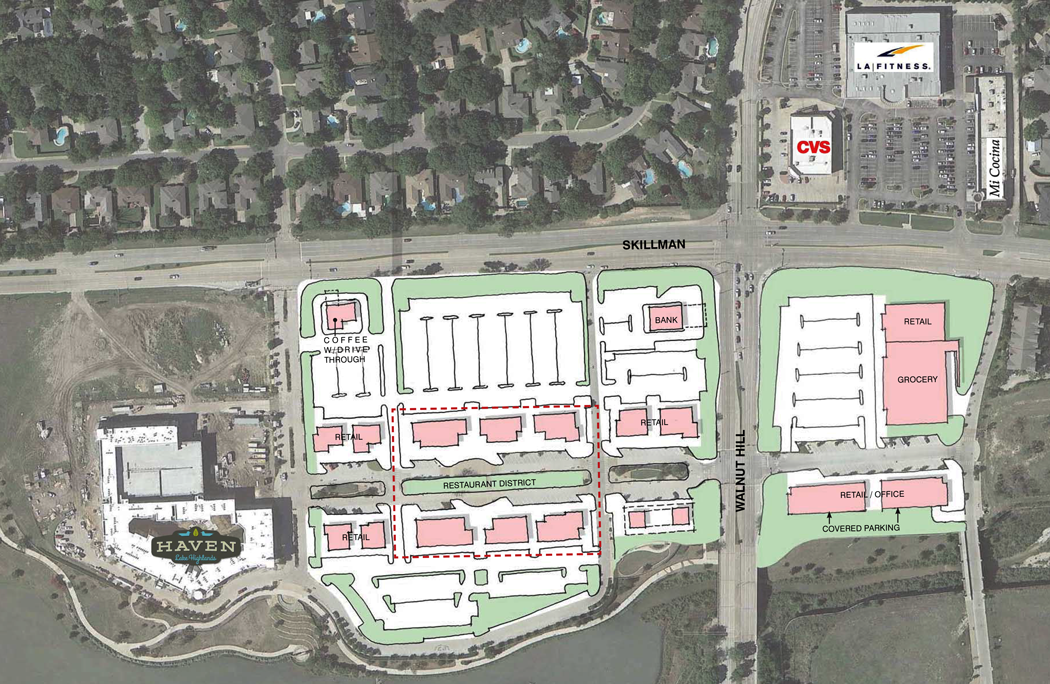

At top is the first of two recently revised Lake Highlands Town Center plans Cypress submitted for the City Design Studio’s endorsement, which is required if Cypress aims to receive TIF funds. It was a drastic change from the 2007 plans, which officials and many neighborhood residents supported. The reviewing panel did not bless the plans, calling the changes too substantial and overly suburban in character. Cypress took a month to revise the plan, based on the panel’s suggestions, but returned with renderings that showed only slight changes (below) — some slight variations in building sizes, a shift of a clock tower from the east to the northwest corner of the property, and little else. It was not enough for the City Design Studio’s panel. Cypress “called a timeout” and representatives are determining their next step.

By 2010, five years and $23 million dollars of public sector time and treasure had been invested in the Lake Highlands Town Center. But the new economic reality that emerged as the real estate industry recovered from recession would jeopardize the core of the project.

While the public-sector work of abating asbestos, demolishing structures, building bridges, grading and paving streets, and installing landscaping and trails got underway, the private sector took a beating. The Great Recession struck in 2008, hitting the real estate business especially hard as project-financing sources dried up and demand from tenants evaporated.

Previous timelines, density considerations, TIF reimbursements and other elements needed to be reconsidered in light of the new normal. The City of Dallas hired Street-Works, LLC, a nationally recognized development-consulting firm known for its transit-oriented developments, to do an independent analysis of the town center project.

Working with the firm and the city, Prescott rehashed its plans. Among the agreed-upon changes were a slightly altered density mix, an extended timeline for completion, and an eligible TIF reimbursement increase from $23 million to $40 million.

Like many ambitious real estate projects, the center was owned by a partnership of a local operator and institutional capital. Dallas-based Prescott’s partner and primary capital source was Austin-based investment firm Cypress Real Estate Advisors.

In 2012, after six years of involvement, Cypress asked Prescott to step aside, at which point it became not only the capital source but also the face of the project, and hired local resident Bill Rafkin to lead the way. There was a new sheriff at town center.

The holy grail of neighborhood retail is a well-run, profitable grocer. Landing such a tenant would validate the site and draw other retailers hoping to draft behind residents’ regular grocery trips.

Cypress officials won’t confirm that the town center anchor is Sprouts, a successful farmers-market style supermarket, but documents on file with the city name Sprouts on site plans and renderings. It’s no secret that Sprouts has committed to the project, as much as an anchor tenant can commit when all that exists are preliminary architectural plans.

Sprouts has its own ideas about where it wants to position stores on a site, and Cypress revised its plans to satisfy the grocer. But the new plans did not pass muster with the City Design Studio (CDS) and its appointed Urban Design Peer Review Panel, both of which must review projects that seek TIF reimbursements.

The revisions, including a 28,000-square-foot Sprouts, were too dramatically different from the original design, the panel said, when the neighborhood and its elected officials had so enthusiastically backed the project.

A second, revised plan was presented to the panel a month later, with similar results. (See Cypress’ two renderings on p. 40.)

The developers and the City of Dallas reached a stalemate.

Sensing temperatures rising, Cypress “called a timeout” says Rafkin, the firm’s local representative.

“It became very apparent there were two different visions for the project and that with the passage of time and reflection,” some progress could be made, Rafkin says.

Cypress already fulfilled its TIF requirement to construct the Haven apartment complex and build and lease at least 60 percent of the ground-floor retail space, which is good for $8.6 million in reimbursement payments. Combined with $1.6 million it received in 2011 after the completion of the 20-acre Watercrest Park near The Haven, its TIF reimbursement total is now $10.2 million.

The town center stands to benefit a grand total of $40 million, however, thanks to 2011 amendments to the TIF agreement.

Of course, Cypress could reject TIF reimbursements and build whatever it likes under existing zoning, but that would mean foregoing roughly $30 million the town center could recoup by cooperating with TIF requirements.

So the larger question remains: What will the town center look like?

The fact that urban planners are prone toward elitist vocabulary is unfortunate, says Kevin Sloan, an architect who co-chairs the peer review panel that opposed Cypress’ most recent plans, because it keeps residents from feeling like they can engage in the conversation.

“Urbanism is somewhat hard to understand at a verbal level,” Sloan says, but whether or not neighbors know the terminology, “when they see it, they know whether it’s right or wrong.”

In the case of the Lake Highlands Town Center, the panel took issue with the “suburban character” of Cypress’ proposal. “There’s nothing close to urban about this project,” Sloan says.

Rafkin argues Cypress’ revised plans are right for the Lake Highlands Town Center, and he is trying to steer the conversation away from urban versus suburban.

“Our design of the retail center at Lake Highlands Town Center has been unfairly labeled as too suburban … we need to change our vocabulary from ‘suburban’ versus ‘urban’ to ‘extraordinary’ versus ‘ordinary.’”

He says Cypress hopes to create a “village green” with places to shop, to gather, to play — a place where people would want to linger.

But what exactly that looks like remains to be seen.

District 10’s new city council representative Adam McGough, a lawyer who has a background in mediation, has promised his constituents to listen to their desires for the town center, convene the stakeholders and push for an agreement that will launch the project into the next phase. He took a step in that direction last month at a town hall meeting with representatives from the city, Cypress, Richardson ISD and about 250 interested neighbors. Even Mayor Mike Rawlings attended and voiced support for action. McGough told the group he will convene a “community task force” to find a resolution the neighborhood can support, so construction can start.

Richard Duge

Richard Duge is president of the White Rock Valley Neighborhood Association with its 1,300 homes, which are due east of the Town Center project, across Jackson Branch Creek and the DART rail line. The neighborhood association has taken a special interest in the town center’s progress because of its residential proximity and potential effect on the desirable White Rock Elementary. Duge authored and distributed a neighborhood survey on the town center that received more than 2,000 responses from Lake Highlands residents. Duge says he plans to share the survey results with Cypress and with Councilman Adam McGough in hopes of molding the direction of the project. To see the results, visit lakehighlands.advocatemag.com and search “survey says.”

One, Cypress can pick up where the stalemate started. Re-engage with the city’s design review panel. Is a compromise possible? Rafkin has his doubts. “We just have philosophical differences with city planners,” he says.

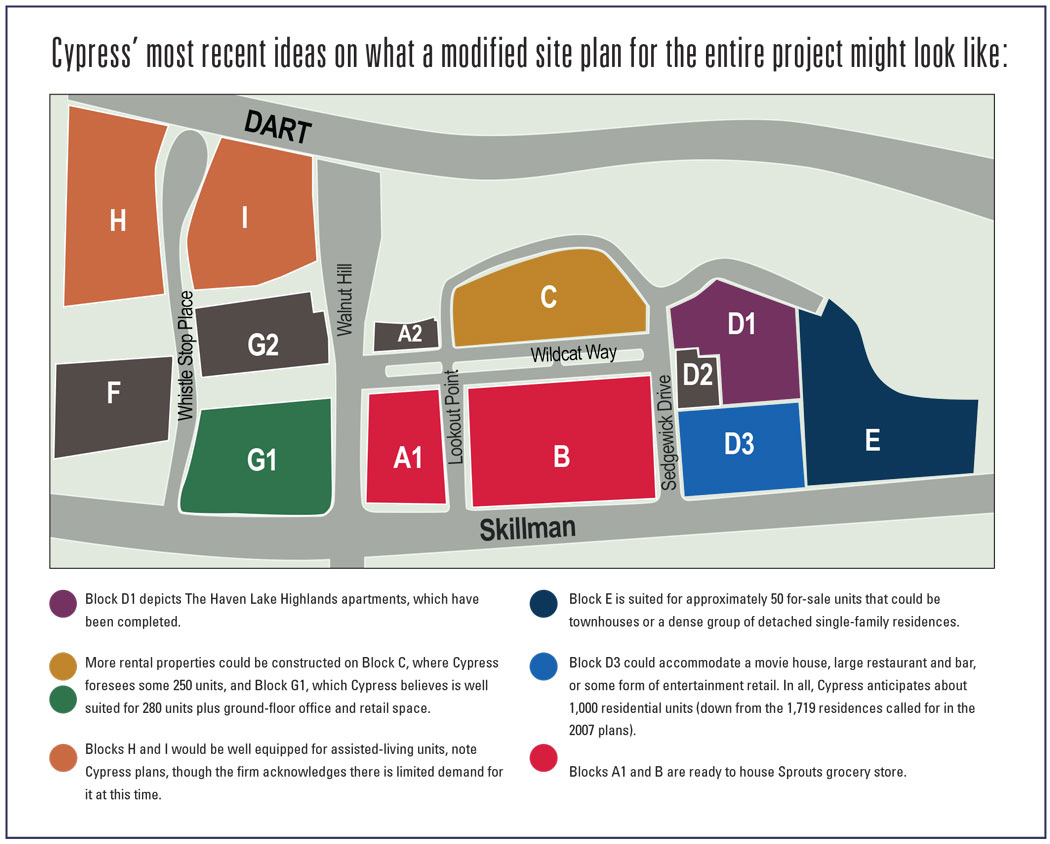

Two, modify and amend the TIF to allow Cypress more time and flexibility for design characteristics. Most TIFs are modified in some manner during the course of their economic life. The Skillman Corridor TIF, whose current life is through 2035, already was amended once in 2011. (See Cypress’ ideas on what a modified site plan for the entire project might look like on opposite page).

A TIF modification would extend the 2019 deadline for Cypress to fulfill requirements making it eligible for the remaining $30 million in TIF funding. In this scenario, Cypress would still need to satisfy both the potential grocer, Sprouts, and the city’s design panel — otherwise, the project would head back to square one.

But will the new leadership at the TIF board support a modified plan?

“We need to take a step back and take a deep breath,” says John Dean, chairman of the Skillman Corridor TIF Board. “While Lake Highlands has changed significantly since the TIF was created 10 years ago, the TIF remains basically unchanged. I could support a modification of the TIF as long as we fully understand what is next.

“Let’s understand why the current plan is out of date but still protect the city and taxpayer investment.”

Finally, Cypress could end its participation in the Skillman Corridor TIF, meaning it would forego the remaining $30 million in TIF funding made available to the firm in the 2011 modification.

Cypress still would have to meet current zoning requirements outlined in Planned Development District 758, a special zoning district for the center, which, among other things, establishes setbacks, building heights, and parking and landscape requirements.

“There is nothing unworkable for Cypress in the existing zoning,” Rafkin says. Most importantly, in this option, Cypress wouldn’t need the blessing of the city’s design review panel on any project. But it would cost the firm $30 million in potential TIF funding.

Tip Housewright

Tip Housewright is a 20-year resident of Lake Highlands and president of the Lake Highlands Public Improvement District (PID). He is a principal with Omniplan, a nationally recognized architecture and design firm. Acknowledging that “nobody asked me to draw up my ideas on a plan,” Housewright’s longtime residency, neighborhood leadership and professional design expertise give him a unique perspective on Lake Highlands Town Center.

“Maybe the original vision overshot the neighborhood and placed too much emphasis on multi-family and structured parking. Lake Highlands needs a community gathering place, a ‘downtown Lake Highlands,’ not another strip shopping center. We have waited years for this opportunity and we need to get it right. Lake Highlands residents, myself included, all want more quality restaurants in our community. My plan creates a place that will activate Wildcat Way as a great place for restaurants and create a heart to the town center property. We need to create a strong phase one that will lead to an even better project in the future.”

As of 2015, Cypress’ clients have invested more than $50 million in the Lake Highlands Town Center. Fortunately, there is no debt on the property, so the threats of an unhappy lender won’t force anyone’s hand to make a bad long-term decision. But a good local economy, a new city councilman, new local owner representation and a grocery anchor commitment have created a sense of urgency that didn’t exist last year.

For a decade, Lake Highlands Town Center has been the real estate equivalent of a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, encased in an enigma.

This could be the year of unwrapping.